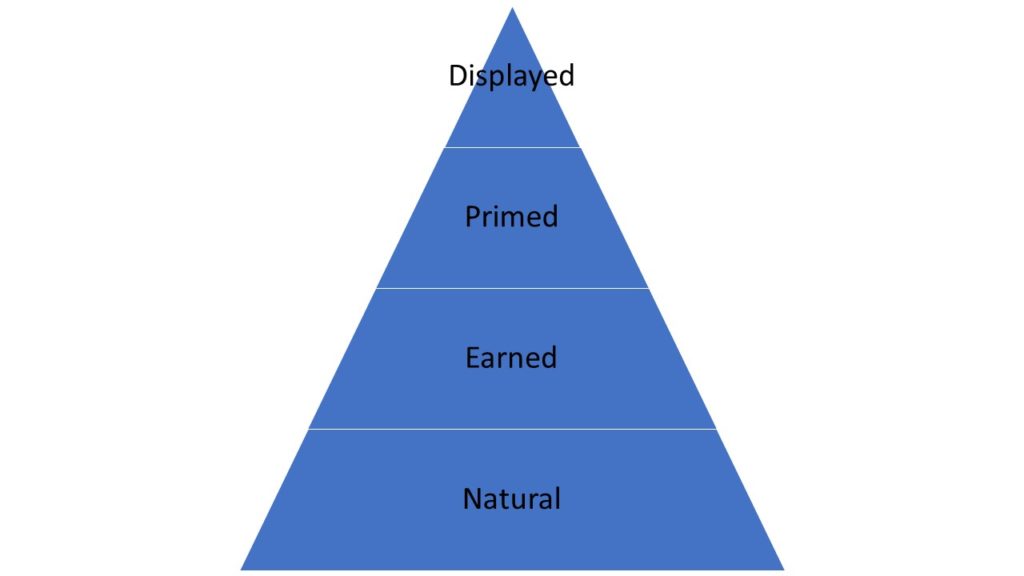

In my last blog post, I wrote about the foundations of confident communication, the factors that prop up the confidence you feel coming into the presentation or conversation. Adding to whatever natural confidence you possess, if you‘ve done the work to have high earned confidence and given yourself an additional boost with some priming techniques, that inner confidence will spill out in your displayed confidence, like the light and sound from a party house on a darkened block.

A lot of that confidence will genuinely display itself in your body language: you will be more open, stand a bit taller, and face people squarely with a smile. Even if you’re still nervous, you can to some extent “fake it “til you make it” by consciously trying to show more than you feel.

And yet, despite all your efforts, there is still one more factor to consider, which in my experience is most often overlooked: your actual language. That’s because the human mind is exquisitely tuned to detect cues that indicate strength (and warmth). We’re no different than the animals we see on nature shows that use body language displays to indicate strength and status, but unlike them we also have spoken language which contains subtler but no less important cues.

Your actual language—the words you choose and the style and structure of your speech patterns—can be hugely important in determining how confident others perceive you to be.

Verbal confidence (or lack thereof) comes through in three ways: directness, clarity and power leaks.

Directness

Direct language is confident language. Direct = confident. It shows you have enough faith in your own idea that you want to show the world your idea in all its naked reality, without dressing it up in little detours or decorations. Get right to the point, don’t mitigate your message. “Turn up the heat” is far more direct and confident than “is anyone else cold?”

Winston Churchill, who probably did not have an unconfident bone in his body, said: “If you have an important point to make, don’t try to be subtle or clever. Use a pile driver. Hit the point once. Then come back and hit it again. Then hit it a third time – a tremendous whack.”

Clarity

The perception of your confidence is also affected by the clarity of your message, because when people aren’t sure what you mean they may think that you’re either unsure yourself or trying to hide something. Clarity depends heavily on the words you choose. Here are three ways to

- Weasel words, which Josh Bernoff, author of Writing Without Bullshit, calls adjectives that seem to add power but actually weaken your speech, such as very, tends to, many. Try to give them a number, or leave them out.

- Euphemisms mean well but we’re so afraid to offend anyone nowadays that we contort ourselves into knots trying to figure out how not to say something, such as United’s assertion that the passenger they beat up was “re-accommodated”.[1] Think what you would say is someone asks, “What exactly do you mean by that?”, and start with that.

- Abstraction is not necessarily a bad thing, because it’s often the only way to describe complex ideas. But unless you prop them up with examples that listeners can picture in their minds, it can be like trying to grasp a heavy object without a handle, not impossible but harder than it needs to be. When you can easily spout numbers, facts and names, it adds power and confidence to your communication.

Power leaks

Despite your best efforts to be direct and clear you may still suffer from what I call power leaks. These include:

- hedges, such as, “I think that, maybe…”

- hesitations, “such as kind of, sort of…”

- filler words, “um, you know, like…”

- tag questions, “don’t you think?”

Unless you pay close attention to your own speech patterns, you may not even be aware that you have power leaks. Ask a trusted friend or associate to tell you if they notice them, and then focus on breaking the habit.

In sum, if you want to be perceived as a powerful and confident communicator, be direct, be clear, and cut out the wimpy power leaks.

[1] I was once told by a client that I could not use the term “flip chart” because it might be offensive to Filipinos!

The level of confidence that you display to others can have a huge impact on your credibility and persuasiveness, but what people see is only the tip of the iceberg. While others only see what’s above the surface, that visible portion is hugely influenced by what’s beneath:

How much of what’s beneath the surface is under your control?

Natural Confidence

Some people are simply born with more confidence than others, a fact which is obvious when you compare your friends and acquaintances. They blithely charge ahead in situations where others may hang back, seemingly sure that they will get what they want regardless of the situation.

It may seem unfair, but often that confidence becomes self-fulfilling and self-reinforcing, for two reasons. First, by daring more, naturally confident people tend to win more (as long as they avoid catastrophic misjudgments), which of course confirms and reinforces their confidence. Second, the positive feedback loop is also fueled by the increased confidence of those who surround them.

It’s also backed by science; a recent study involving twins determined that self-confidence is at least as heritable as IQ, so there is clearly a “nature” component to confidence. Being extraverted also helps; being comfortable around other people and being the center of attention is a head start.

But we’re not going to spend any more time on the natural sources of confidence here, because you don’t get a Mulligan on choosing your parents. We’ll focus instead on what you can do to create and build on whatever you have naturally.

Earned confidence

Earned confidence is the most important factor under you control. It comprises two parts, general and specific. General confidence is that which you develop through your life experience and achievements, your status within the group, and your learning. You can increase your general confidence by continuously learning, building up your general competence, and successfully facing your fears by exposing yourself to stressful situations.

Specific confidence is what you have in a given situation, earned by ensuring that you have sound content and competence for that topic, that audience, and that time. When you thoroughly know your topic and you’re pretty sure you can get the other person to agree with your point of view, how can you help but feel confident? Being also promotes confidence, because the discipline and effort you put into clarifying your message will boost your confidence in that message, and in turn boost your listeners’ perception of your credibility.

Probably the most succinct statement of specific earned confidence is what Davy Crockett wrote on the title page of his autobiography: “Be always sure you’re right, then go ahead.”

Earned confidence is absolutely the most important layer of all, because it is completely in your control and it is the hardest to shake, even in the most stress-filled or intimidating situation. As Elaine Chao said, “Expertise empowers.”

If you are blessed with natural confidence and have prepared extremely well, you can stop reading now. But if you need just a little more of a boost, here goes:

Primed confidence

Even with a clearly-earned right to complete confidence, it’s still possible to be nervous despite yourself. Your conscious mind may know there’s nothing to fear, but your unconscious mind may not have gotten the memo. Besides, you can have a strong conviction that you are right and still feel a lack of confidence in your ability to get others to buy into your point of view, or you may have pre-speech jitters despite your solid grasp of your material. It’s completely natural to feel anxiety before a high-stakes meeting or big speech, and it’s just as natural to misinterpret that stress as a bad thing.

So, you may also need to get your head straight by priming your confidence level. Priming means getting yourself into the proper frame of mind to increase your felt confidence level. It prepares your unconscious mind to direct your behaviors when you speak to others, which saves you from having to spend your precious mental bandwidth thinking about your outward behavior.

This is where the psychology gets interesting. Your state of mind can influence your bodily behaviors, including posture, movement, gestures and facial expressions. But it also works in the other direction: your bodily behaviors can also influence your state of mind. Your feelings affect your actions, but your actions also affect your feelings. In fact, at any given moment, you are subconsciously reading your own body language to infer how you feel!

So, there are two general ways to boost your confidence before the meeting. You can prime your mind by changing your body, and you can prime your body by changing your mind.

Changing your body. It’s called embodied cognition: your mind takes cues from your body to help it decide how you are feeling. For example, studies have shown that simply clenching a pencil in your teeth, so that your lips are forced upwards, can make cartoons seem funnier.[1]

More importantly, acting confidently, such as taking up space and adopting “power poses”, can make you feel more confident. Doing this before your important talk boosts your confidence and actually carries over into the actual situation. Amy Cuddy and her colleagues found that the mere act of adopting a power pose for just two minutes raised testosterone levels and depressed cortisol in their test subjects. The former is associated with dominance and power and the latter is associated with stress.

They also found in a different study that subjects who adopted power poses before mock interviews were rated more highly and were more likely to be “offered the job” than those who put themselves in a closed, low power position.[2] The subtle part of the study is that there were no observable differences in behavior between the two groups during the interviews – but somehow they projected a more confident and assertive demeanor which translated to more credibility.

A power pose is one in which you open up and take up space. Stand with feet spread and place your hands on your hips with elbows out, or place both hands on a desk, more than shoulder-width apart. You can even do it sitting down; if you can get away with it, place your feet on a desk and lean back with your arms behind your head.

The important point in all of this is that you want to be fully “on” before important communications, and just like an old-fashioned vacuum tube television, you need a short warm-up period to get there.

Changing your mind. Take a minute to think back to a time when you spoke to a room full of people and you really rocked. You were totally on top of your material, you were confident and articulate, and you felt the almost scary power of having every single person tuned carefully into what you were saying. Can you picture the scene, maybe remember what you were wearing, or how you sounded? It felt good, didn’t it? You’re probably sitting up a little straighter and smiling a bit right now.

Now, imagine going through that same thought process before an important meeting or presentation. If you’ve already earned the right to be confident, it will be like lighting the afterburners on your confidence. You will feel much more confident, you will project that to the room, and your credibility will soar.

The process we’ve described is called priming, which means getting your mind into the right state before your performance. Actors do it – the best actors aren’t faking the emotions they show, they are actually feeling those emotions because they have gone through what’s called an “offstage beat”, in which they primed their minds to feel the right emotion for the scene.

There’s another equally important benefit to this. You can only feel one emotion at a time, so focusing on the right emotion will keep you from obsessing on the wrong emotion, the fear you feel before the speech.

What emotions do you want? I personally like to focus on the thrill of giving my listeners useful information that can make their lives better. Jack Welch used to prepare so much for some outside speeches that he would work himself into feeling that he could not wait to share his ideas. Think of a time when you had exciting news that you could not wait to share with someone. (In my case, I recall the time when I called my son at school to tell him that the mailman had just delivered an acceptance packet from his first-choice school.)

The great thing about priming excitement is that it feels very similar to anxiety, so it’s an easy step from one state of mind to the other.

Besides priming your mood, you can also benefit by channeling your focus. Confidence and charisma are closely related, and communication expert Nick Morgan tells us that charisma is simply focused emotion. Emotions are contagious, and someone who clearly feels an intense positive emotion is going to pass that on to anyone listening. If you can achieve that intense focus, you are going to appear supremely confident to others.

In my next post, I will focus on the visible part of the iceberg: the speech patterns and body language that affect your displayed confidence. But, if you haven’t earned and/or primed your confidence before you start, you have probably already lost.

[1] Dave Munger “Just Smile, You’ll Feel Better!” Will You, Really? http://scienceblogs.com/cognitivedaily/2009/04/06/just-smile-youll-feel-better-w-1/,

accessed May 16, 2014.

[2] Amy J.C. Cuddy and Caroline A. Wilmuth, The Benefit of Power Posing Before a High-Stakes Social Evaluation, Harvard Business School Working Paper, 2012.

Your time is more valuable than mine, so I’ll get right to the point: I recommend that you read Writing Without Bullshit, by Josh Bernoff.

Because so much of your business communication consists of words on screen or paper, you have to be able to write lean if you want to be a complete lean communicator. That’s because even though lean thinking applies equally to spoken or written communication, writing poses its own challenges that require specialized approaches.

How is writing different?

The principal difference between writing and speaking is that written communication is asynchronous, which is a fancy way of saying that production and delivery of the message don’t happen at the same time. That can help or hurt your communication.

It can help because usually the first time you say something, you don’t say it as well as you could. Writing is like a ballistic missile: you can choose your target and take pains to aim properly. You can take time to think carefully about what you want to say and choose your words, and you can edit and polish as much as you want. On the receiving end, the reader can absorb your message at their own pace, re-reading if they have trouble understanding or skimming over parts that they already know.

It can hurt because if you’re off target, you don’t have the feedback loop of real-time dialogue which allows you to adjust, clarify and take in the listener’s viewpoint to improve your original message. Plus, if you write the way you were taught in school, you’re almost guaranteed to produce crappy writing. That’s because the sole purpose of writing in school is to make yourself look smart, not to help the reader improve their outcomes.

That presents a great opportunity for a good writer. Since most business writing is bland, boring or baffling, you can easily stand out and make a reputation for yourself by just being a little better than everyone else. Unfortunately most people throw away the advantages of writing by not taking the time to carefully craft and edit their message, so the bulk of business writing is full of waste, or to use the more colorful term: bullshit.

So what?

Fortunately, Writing Without Bullshit supplies the antidote. If I were to write a book on Lean Communication as applied to writing (and if I were a better writer), this is the book I would have tried to write.

So much of what Bernoff writes aligns closely with LC principles. That’s no coincidence, because a lot of my LC ideas have come from studying and trying to apply ideas from books on writing. Lean keys such as outside-in thinking, Bottom Line Up Front, and Transparent Structure all apply as well to writing as they do to speaking. But this book brings a writer’s perspective to the principles.

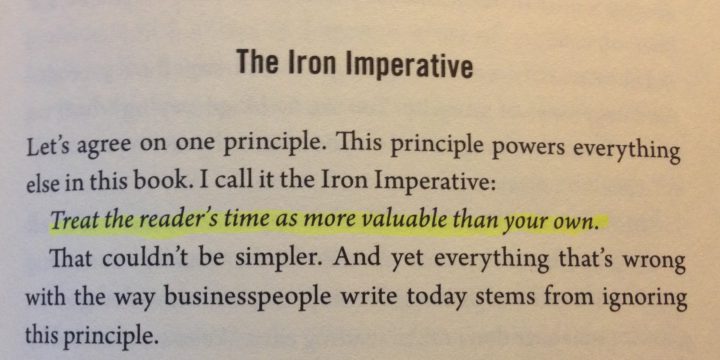

Let’s just focus on one his Iron Imperative, which you see reflected in the picture above this post:

Treat the reader’s time as more valuable than your own.

That’s Outside-In Thinking, applied to writing. It’s powerful because it focuses your mind on adding value to the reader without wasting their time. If you stick a post-it note with it on the top of your computer screen, it will remind you to take the time and make the effort so that your reader won’t have to, and it will hugely improve your writing[1].

Actually, that’s not exactly true. You will throw away the advantage you have as a writer if you don’t take the time and make the effort to carefully craft your message and choose your words. That’s why the second half of the book is so valuable. It’s about the project management aspect of writing, and it will teach you how to be productively paranoid, find your flow, and edit your own and others’ work effectively.

The nice thing about becoming a better writer is that it will make you a better speaker as well. So if you truly want to add value with less waste no matter what medium you use, you must learn to get rid of the bullshit. You—and the rest of the world—will be better off.

[1] I would be guilty of peddling bullshit myself if I didn’t disclose some disagreements I have with Bernoff. While I agree with his Iron Imperative, I don’t believe it says enough about understanding the reader’s perspective and their needs. If the purpose of business writing is to change the reader, as he says, then one should think more deeply about the WIFM when writing.

Gauging from what’s happening in politics this season, fact-based persuasion has gone woefully out of style. And it’s not just politics—one of the most common themes in the sales and persuasion blogosphere is that emotion rules persuasion. You don’t need to have a detailed grasp of the facts to make your case, because anyone can look up the details. Impressions and emotions sway decisions, numbers and details simply bore people.

But when you tear yourself away from a computer screen and pay attention to what’s happening in the real world, it’s clear that having a deep command of the facts—and being able to speak them at the rate of normal conversation without having to use your slides as a crutch—still has tremendous persuasive power. In fact, when everyone else is relying on vague, unsupported emotional appeals, those who state their case calmly, but with airtight confidence based on a tenacious grasp of the evidence, can stand out because hardly anyone does it anymore.

I’ve seen this phenomenon repeatedly over the past several months, as I’ve been involved with a group that has been fighting a battle against overdevelopment in my city. Our little band of dissidents lacks the money or influence that the developers and politicians have, and we’ve learned the hard way that emotional appeals at City Commission meetings are simply ignored. But we’ve also figured out that we can get attention by carefully researching the issues and backing up everything we say.

We’ve also learned that nothing is drier than too many numbers in a presentation, right? Actually, I’ve seen that if done correctly, rattling off a series of numbers from memory can have an enormous impact on the minds of your listeners. Paul, a member of our group, is a master at this. When we met with the editorial board of our local paper to make our case, Paul began explaining the public safety impact that the project would have, citing numbers such as response times, traffic delays, number of incidents, etc. Halfway through his spiel the paper’s editor interrupted and said: “You have an amazing grasp of the numbers!” That’s when I knew we had made our point.

In another public meeting, Paul’s detailed analysis of the weaknesses in the developer’s traffic study was so devastating that when the traffic expert tried to rebut his testimony, every time she mentioned a number, she looked at him as if she needed approval.

These examples point out another benefit of fact-based persuasion. When people are already emotionally invested in their own opinion on a matter, it’s extremely difficult to change their minds with an emotional appeal; they will simply dig an and defend their point of view even harder. Even if they agree with you, conceding your point may make them lose face. But if confronted with irrefutable facts, this “new information” gives them an honorable way out of their position, and they can show themselves to be reasonable people by changing their minds. This is especially important if you’re challenging those who are more powerful; a torrent of facts can be your best protection and surest way to succeed.

There is one key to keep in mind if you want to use details to impress and not to simply bore people. State the bottom line up front and then support it with numbers. As John Medina says in his book, Brain Rules: “Meaning before detail.” People will lose interest if they don’t know what your point is right away. When they grasp the meaning, they can much more easily pay attention to and absorb the necessary detail.