One of the tenets of lean is constant and continuous improvement, and in that spirit I have modified my model slightly, thanks to a new Harvard Business Review article by Nick Toman and Brent Adamson, The New Sales Imperative.

As I’ve written before, your purpose—in fact, the only reason salespeople are relevant—is to help your customers make effective buying decisions. Complex decisions can’t be made without investing time and effort to gather, understand, analyze and apply a lot of information, but salespeople often make it much harder than it should be. To that end, the goal of Lean Communication for Sales is to improve your buyers’ RoTE, or Return on Time and Effort. In lean terms, you provide useful information that helps improve their outcomes, and express it concisely and clearly.

To a great extent, their article reinforces what I’ve been saying about the importance of making it easier for people to decide. As their research shows, making buying easier results in a 62% increase in the likelihood of winning a high-quality sale.

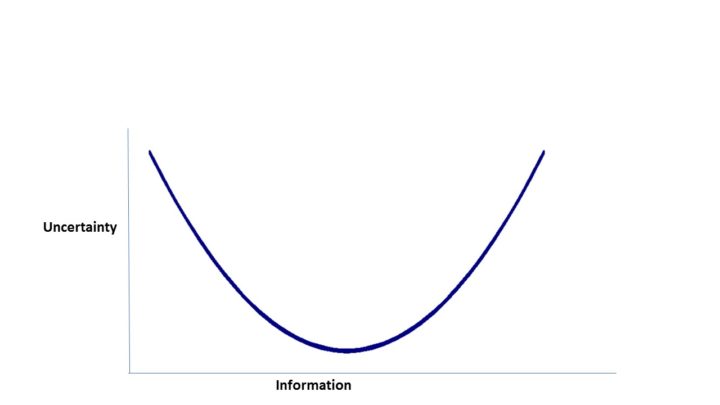

But as new research that Toman and Adamson adduce shows, there is another hidden form of waste that needs to be removed from the buying journey: uncertainty. Their research shows that customers are “deeply uncertain and stressed”, and second-guess their decisions more than 40% of the time! This uncertainty can be paralyzing, and paradoxically it’s the good intentions of the salesperson that exacerbates it. That’s because they try to be responsive and attack uncertainty with even more information. But unfortunately, beyond a certain point, more information and more choice actually increases uncertainty, as you can see in the figure above.

This is a useful reminder, but most of us already have at least an inkling of this. The real difficulty is figuring out where the bottom of that curve is so that you can get uncertainty as low as possible but then stop. That’s where their article is particularly helpful. They lay out a four-step approach for being less responsive and more prescriptive. Out of deference to them and to HBR, I’m not going to try to summarize their ideas here—I encourage you to read it here.

What I am going to do, however, is spend some serious time thinking about how to incorporate the idea of reducing uncertainty into Lean Communication for Sales. As a start, I’m changing the goal of improving RoTE to RoUTE!

Let’s start today with a quick test:

- Which well-known company listed its values as,

“Integrity, Communication, Respect, Excellence”?

- Which well-known company said,

“Earning lifelong relationships, one customer at a time, is fundamental to achieving our vision.”

If you answered “Enron” for question 1 and “Wells Fargo” for question 2, go buy yourself a cigar.

Enron had its four values prominently displayed in the lobby of their headquarters building, right up to the day that they were shut down for massive fraud. Wells Fargo apparently thought that lifelong customer relationships were best pursued by striving to cross-sell eight accounts to every customer, even if the only way that most employees were able to achieve their sales targets was to act like “lions hunting zebras” and open accounts without authorization or to sell unneeded products, preying especially on those who were least in a position to do anything about it.

Enron and Wells Fargo are extreme examples of the mismatch between stated values and actual behavior. I see examples of mismatches on a much smaller scale everywhere I go, and I’m sure you do too. But the problem with even small scale transgressions is that if left unchecked they can insidiously erode positive values drip by drip until one day you wake up to find that the actual culture bears little relation to the stated one.

Hypocrisy can either be intentional or unintentional. I believe that in the case of Enron it was intentional and systemic, because the people at the top were leading the charge and were immersed in fraud and criminal behavior up to their necks. If you’re one of those people, there’s not much I can say other than I hope you get caught sooner rather than later.

In the case of Wells Fargo, no one has proven that CEO John Stumpf was knowingly in on a conspiracy, and I am going to proceed from the assumption that he was not. Yet he did allow the conditions to exist that led to wrong behavior, even if he did not mean to. And that’s the important point of this post: vision and values are fragile and require constant cultivation and care if they are to take solid root and bear fruit. More importantly, it’s easy to kill the plant, so the first rule is “don’t do stupid stuff.”

Stupid stuff that erodes well-meaning vision and values includes:

Communicate, communicate, communicate

By all means, post your vision and values prominently in your lobby. When I work with a company, of course I research them and one of the first things I look for is to understand their stated vision and values—yet I’m constantly surprised when I find that many of the employees I work with can’t even tell me their own company’s vision statement, or give me quizzical looks when I mention one of their values!

But don’t stop there. Constantly be on the lookout for examples and share stories that reinforce the message. Publicly praise and reward employees who exemplify the values you cherish. Just as importantly, remember Voltaire’s quip: “It’s a good thing to shoot an admiral now and then to encourage the others.”[1] When you announce a major decision or change, explain it in terms of your values.

Most importantly, model the values yourself. Employees pay far more attention to what you do than what you say. It’s like a parent telling kids to stay away from drugs, when they down three or four drinks every night at home.

Pay close attention to the goals you set

Continuing the theme of communication, what is the most powerful message medium a company can have? It’s the one corporate document that every employee reads: their paycheck. If you’re told to act a certain way but rewarded for acting in a different way, something has to give, and it probably won’t be the one that makes you money or keeps you employed.

In Wells Fargo’s case, their unrealistic goals and excessive pressure on results sent a far more powerful message than their stated values. For example, one of their values was:

“Our team members are our most important constituents because they’re the single most important influence on our customers.”

That’s a beautifully expressed and on-target sentiment, but what was the reality? According to the lawsuit filed by the City of Los Angeles in 2016: “Managers constantly hound, berate, demean and threaten employees who fail to meet these unreachable quotas.” That’s because the bank was targeting an astounding cross-selling target of eight accounts per customer. As their 2010 annual report said, “Eight rhymes with great.” Here’s a hint, if your goals rhyme, you may want to take a closer look at them.

As Emerson said, “What you do speaks so loudly that I can’t hear what you say”. What are you saying by your actions?

[1] Admiral John Byng of the Royal Navy was shot in 1757 after being court-martialed for “failing to do his utmost” in a naval battle.

I had the privilege yesterday of meeting and listening to probably the most energetic Canadian I’ve ever met. Jamie Clark was the keynote speaker before me at a sales kickoff here in Fort Lauderdale. We had never met and we certainly did not coordinate our talks, but I was struck by the similarity of messages that we both delivered.

Jamie is an adventurer and entrepreneur who has climbed the Seven Summits and made four attempts on Everest, the last two of which were successful. He spoke about the first three attempts, and rightly spent most of his time talking about his failures, because in many ways failure is probably more interesting—and certainly more educational—than success.

Failure is interesting and educational because when properly handled it provides painful but useful information about your weaknesses and the gaps you need to close to become good enough to reach an ambitious goal. As Jamie told hilarious stories about his early mistakes and rejections, he stressed that one thing he had going for him was that he always asks why he failed. When he was first turned down to join the expedition team for his first Everest attempt, he went back and asked way, and was told, “Because you’re an idiot.” But at least this idiot figured out a way to be a little less of an idiot and eventually found a way to weasel (his word) his way on to the team.

I won’t go into the rest of the fascinating details of his talk (mainly so he can’t sue me for plagiarism) but one theme emerged very clearly as Jamie’s story unfolded. Through the years that it took to finally reach the summit, Jamie found that the less he thought about himself and the more he thought about the good of the mission and the team, the closer he got to his goal. He called it “service to the mission”, and it was a powerful message.

My talk was more in the form of a workshop than an inspirational speech, but my central idea was exactly the same, albeit with different words. I’ve written many times in here about outside-in thinking, which is the ability and the attitude to look at things from the perspective of your customer. When you focus on making your customer successful, good things will happen and you will be successful too. The more you focus on what you want the further it gets. Outside-in thinking ennobles the purpose of your profession—as Churchill said, “We make a living by what we get, but we make a life by what we give.”

You’re a salesperson, so you probably aren’t going to have a mission as exciting as climbing the world’s tallest peaks. But if you make it your mission to make your customers successful, and you serve the mission faithfully, you can definitely reach the heights of your profession.

No, it’s not a typo. Megative is a word I’ve coined to describe the tendency some people have to puff everything up; everything is mega. Megative people use awesome and world-class to describe even the most average and mundane things. To them, everything is the greatest, or the absolute worst. There is very little middle ground or nuance, because moderation is for sissies. More familiar synonyms are hyperbole, puffery, immoderation and bullshit, and in this post-truth time we’re living in, it appears to be getting more and more common. But is it bad? Is megative negative?

If I were to be megative, I would stake out an extreme position and tell you it’s the worst thing in the world or the best. But the truth is, it depends.

First, it depends on why or how it’s used. There are four types of megativity which I can think of. (There may be more, but since I made up the word, I can claim to be the world’s greatest expert on it.) Starting from the most positive and heading downhill from there, they are:

- Built-in megativity, which is a natural part of your personality. The best example I can think of is my friend John Spence, who looks at the brightest possible side of anything he encounters; even when you think he overdoes things, you don’t mind because his enthusiasm is infectious.

- Marketing megativity, which is using it as an effective tool for influence, as in the examples I’ve described. People may discount it, but they see it as a legitimate form of expression, and in fact if you aren’t exaggerating a little, maybe you’re not trying hard enough.

- Dunning-Kruger megativity, so named because of the psychological effect whereby those who are least competent in a topic are most self-confident. D-K megativity is ignorant self-delusion, where you actually think you are the world’s greatest. By coincidence, the initials match nicely what I call DK², which is when you don’t know what you don’t know.

- Bald-faced lying. When Trump says such and such a policy will be terrific, it’s tough to tell whether it’s marketing or self-delusion. But when he says he won one of the greatest landslides in history, that’s outright lying. (Obviously, since he won the election, it worked for him. But you’re not him and you’re a serious business communicator, so don’t try it.)

Megative statements have the power to persuade, or they can backfire on you. Let’s look at the pros and cons:

The Pros

The first two types of megativity can make you a more persuasive communicator, for the following reasons:

It can grab the audience’s attention. In his new book, Thank You for Being Late, Thomas Friedman writes: “The moment that Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone turns out to have been a pivotal junction in the history of technology and the world.” You can’t get any more megative than that. Whether you agree or disagree with the statement, you’re compelled to keep reading, to find out why he says that or how he backs up such a brash statement.

Megative statements are especially useful to snap your audience into attention at the beginning of presentations. Once, I taught a class on presentations to senior executives, and I began by saying: “Welcome to possibly the most important class you will ever take.” When I said that, I had every eye in the room riveted on me, and I knew I had them. (However, note that a truly megative person would not have used the word possibly.)

Megative statements, even though they are by definition less likely to be true, can actually make you more credible because they exude confidence, and confidence sells. Being social animals, humans are exquisitely sensitive to verbal and nonverbal cues that indicate relative levels of status within groups. Those who act more assertively and confidently tend to be accorded higher status, and in general are perceived to be more competent than they actually are.[1]

Megative talk sells, because it shows passion and enthusiasm. As the world’s master of megative talk says: “People may not always think big themselves, but they can still get very excited by those who do. That’s why a little hyperbole never hurts. People want to believe that something is the biggest and the greatest and the most spectacular.”

Megative talk may also harness the power of anchoring. While they may discount your initial evaluation, it’s possible that they won’t adjust enough, so you end up closer to where you wanted to be. It’s similar to what Robert Cialdini calls the “Door In The Face” (DITF) influence technique, where you ask for something outlandish and get refused, and then your next request seems much more reasonable.

The Cons

The last two forms of megativity can easily backfire on you.

Others will automatically discount what you say. Megative statements can be like swearing in that they have shock value at first which quickly wears off the more you use them. You also run the risk that the audience will quickly adjust to your statements and automatically discount what you say. Like a drug, you’ll have to use stronger and stronger language just to achieve the same effect.

Megativity is less effective with certain audiences. For example, I work a lot with engineers and scientists who place a huge premium on data to back up what you say. So, if you are going to use it, be prepared to back it up.

At some point, you may be called upon to put your money or your performance where your mouth is. Dunning-Kruger megativity can get you in a ton of trouble, because your claims will inflate expectations that you will then have to meet—and that’s not likely to end well.

Please spread the word—literally! With your help, megative will be the biggest word of 2017, maybe even 2016 if you act now!!!!!

[1] Cameron Anderson, Sebastien Brion, Don A. Moore, and Jessica A. Kennedy, A Status-Enhancement Account of Overconfidence, 2012.