Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Some people you have to believe; some you want to believe. So far, we have covered the elements that compel credibility. With a sufficient combination of credentials, content, candor and confidence, people almost have to believe you, even if they would prefer not to. Even if they don’t like you, those three elements will give you a powerful engine to sail against the current of animosity.

On the other hand, it’s always more efficient, and more pleasant, to sail with the current; if people connect with you on a personal level, they are going to be predisposed to believe you and trust you—or at least give you the benefit of the doubt. Think of it as attracting credibility. Especially if what you’re asking is not that big a deal to them, so they don’t care too strongly either way, they are more apt to give it to someone they like and whom they feel likes them.

There’s a reason that one of the best-selling self-help books of all time was called How To Win Friends and Influence People. Credibility is about influencing the beliefs of others, and winning friends is a clear path to influence.

This article is about connecting with other people on a personal level—winning friends, if you will. To use more modern terminology, it’s about displaying warmth as well as competence.

Competence v. Warmth

Our brains have evolved an amazing capacity to form snap judgments about other people, because our ancestors who were good at it tended to be the ones who survived to pass on their genes. Suppose you’re walking down a lonely street and see a stranger approaching. It’s completely natural—actually inevitable—that you will make a rapid and mostly unconscious calculation about that person, assessing two questions: What are their intentions, and can they act on those intentions? In effect, we want to assess whether they mean us harm and if they do, how much power do they have? These two questions boil down to two dimensions called warmth and competence.

How do the factors we’ve discussed so far fit into these two universal dimensions? The Max Cred factors of Credentials, Content and Confidence fit squarely into the competence dimension. Candor shades into both dimensions: transparency shows strength while its openness about motives and concern with ensuring the other person gets your meaning exudes goodwill. Connection is squarely within the warmth dimension.

Connection is especially important because warmth is actually the first judgment the brain makes—within a tenth of a second of spotting a new face.[1] You can usually tell very quickly when someone has warm intentions, but it can take much longer to accurately judge their competence. It gives scientific backing to the saying: “People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.”

Better to be liked, or respected?

So that brings us to a question: is it better to be liked or respected? It’s an age-old conundrum that goes back at least to Machiavelli, who addressed the question of whether it’s better for a prince to be loved or feared. Even Machiavelli said “One should wish to be both”, but that’s the easy answer. And the easy answer is not so simple, because the relationship between liking and respect is complicated, and because a lot depends on the situation and context.

The relationship is complicated because, while some aspects of competence and warmth can coexist and even reinforce each other, some aspects of each are contradictory.

Let’s start with the case for competence over warmth.

Why did baseball manager Leo Durocher say that nice guys finish last?[2] Is there something about being nice that can actually harm your credibility? Amy Cuddy of Harvard Business School says that people who come across as nice may actually be seen as less intelligent.[3] Jeffrey Pfeffer, a Stanford professor of management, says likeability is overrated—that appearing tough or even mean can improve your perceived competence.

Even in a field like sales, where many people believe it’s all about relationships, there is clear evidence that competence can trump warmth. Adam Grant wrote Give and Take, which is all about the virtues of being a giving person, so you would expect he would come down firmly on the side of EQ over IQ. But after he ran two tests with hundreds of salespeople, he concluded that, “Cognitive ability was more than five times more powerful than emotional intelligence.”[4]

So, if even in a field like sales, brains are more important than social and emotional skills, it would seem that competence beats warmth. If you have to choose, you would probably be better off being a competent jerk than an amiable dummy.

Now, let’s examine the case for warmth

And yet, there is also plenty of evidence—not to mention common sense—in favor of warmth. Common sense tells us that we’re more apt to listen to and give the benefit of the doubt to people who are pleasant.

Besides common sense, there is some good evidence that being seen as likeable can make you more persuasive. Studies that have examined the credibility of witnesses in mock courtroom trials have found that more likeable witnesses were seen as more credible[5], although the effect was more pronounced for women. Robert Cialdini, the godfather of influence studies, includes liking as one his top influence factors.

Doctors who have a warmer bedside manner are more likely to have their instructions followed and less likely to be sued for malpractice. And it works in the other direction: one study found that patients who were perceived as more likeable got more time from doctors and more education from their staffs.[6]

One final point: because people infer warmth much faster than competence, it makes sense to lead with it, which also increases your chances that people will listen to you long enough to discover your competence. You can be the smartest person in the room, but if no one wants to listen, then you’re as relevant as a tree falling in the forest with no one around.

So, being nice clearly pays off. The bottom line is, likeability is not the active ingredient of credibility, but it definitely makes the medicine easier to swallow. It’s nice to be smart, but it’s also smart to be nice!

How to Connect

There are two parallel routes you can take, one internal and one external. The internal path—caring—is all about changing your focus and attitude, and the external—connecting—is about changing your outward behaviors.

Caring: Empathy Is a choice

“I don’t like that man. I must get to know him better.” Abraham Lincoln

I once sat across a desk from a cancer specialist in Miami, as he explained to my friend what would happen during and after his upcoming surgery to remove a cancerous bladder. He was dispassionately and even robotically describing the planned surgery, the difficulties to be expected, and the prognosis. He was very downbeat and pessimistic and was emphasizing the difficulties and the downsides. He was certainly exhibiting the Max Cred factor of candor, but I sensed something was missing, so I said, “Andy is not your typical patient. He’s a former world champion athlete.” The doctor asked which sport, and when I said it was swimming, his demeanor totally changed, as he told Andy about his own attempts at Masters Swimming and then proceeded to treat him as a human being.

That story demonstrates that empathy can actually be a choice you make. Jamil Zaki, who studies empathy as a Stanford professor, says “We often make an implicit or explicit decision as to whether we want to engage with someone’s emotions or not, based on the motives we might have for doing so.”[7]

As further evidence that empathy is a choice, there are studies showing that lack of empathy can be induced in people by priming their economic schemas, which is a fancy way of saying that you get them to focus on profit and efficiency.[8]

Connection: Empathy is a skill

Besides being a choice, empathy is also a skill that can be learned, practiced and strengthened. According to a 2015 article in The Atlantic, “While some people are naturally better at being empathic, said Mohammadreza Hojat, a research professor of psychiatry at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, empathy can be taught.” The article goes on to describe several courses at various medical centers and touts the improvements that have been realized in patient satisfaction and trust.

To be more likeable, here are a few reminders:

- Listen more. It is the best compliment you can give another, and the best way to make them feel important.

- Ask questions. Get to know them as real people.

- Be upbeat. According on one HBR article, “Optimism is also helpful during the interview process, making candidates appear more likeable and capable”.

- Give compliments. Flattery works, even when the recipient knows there’s an ulterior motive.

- Body language. Smile more, make consistent eye contact, and keep an open posture.

- Be expressive. Be yourself, let your emotions show, and don’t be afraid to be vulnerable.

- Use informal speech. Especially when presenting upward, don’t try to puff up your language.

- Be humble. Dial down your confidence a bit.

- Play up similarities and common ground. Like likes like.

[1] John Neffinger, Matthew Kohutt, Compelling People, p. 12.

[2] Actually, what he said was “The nice guys are all over there, in seventh place.”

[3] http://hbr.org/web/2009/hbr-list/because-i-am-nice-dont-assume-i-am-dumb

[4] http://www.giveandtake.com/Home/Blog

[5] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20019000

[6] Axis of Influence, p. 8.

[7] https://www.edge.org/conversation/jamil_zaki-choosing-empathy

[8] The bedside manner of homo economicus: How and why priming an economic schema reduces compassion. Molinsky, Grant Margolis 2012.

A lot of business pundits and bloggers like to brag about how many books they read, and I have been guilty of that myself. For many years I’ve taken pride in the quantity of books I’ve read, in some years averaging up to two books per week. I’ve learned a lot of useful stuff through all that reading, but I also know that the vast majority of my reading has probably gone completely to waste.

The thought struck me a couple of weeks ago when my nephew mentioned a book he is reading, Sea Power by Admiral James Stavridis. I said, “Yeah, that’s a good book, I read it a few months ago.” Then I tried to reflect what specifically I had learned from it, and it was difficult to recall more than just a few scattered observations. There are even some books—and I hate to publicly admit this—that I’ve bought more than once, because I forgot that I had read them several years before!

On the other hand, there are many books that I’ve read more than once, either in their entirety or by having repeatedly used them as a reference, and I recall and use most of what’s important in those books. That’s why I’ve decided that any book worth reading is worth reading at least twice.

In lean thinking terms, there is a huge amount of waste in the reading that I’ve done, and I suspect yours as well. There are at least three forms of waste. The first is what I’ve already described: the forgetting curve ensures that I lose a lot of the valuable knowledge I do acquire.

Second, especially for difficult material, it’s unlikely that I got the full meaning the author was putting across. For a book to be worth reading, it should challenge your thinking in some way, and that means that it should not be easy to pick up its depth and nuance in a single pass through it. If a very smart and wise person said something important to you, you would likely think about it, ask questions, clarify, etc. and that is something you can do with a book by re-reading. When it’s worthwhile and challenging, reading is not enough: you have to study it.

Third, I’ve wasted a lot of time reading material that was not worth recalling. The corollary to this rule, of course, is that if the book is not worth reading, it’s silly to waste any time finishing it.

Besides reducing waste, one more important reason to re-read a book is that, if you let enough time pass between readings, you may be a different person in many ways the second time around. You’ve learned more, acquired new and different knowledge structures, and will probably understand it differently when you read it again. It’s especially fascinating at times to encounter passages I’ve highlighted or read my own comments in the margins, and wonder what I was thinking at the time!

So, read that worthwhile book twice at first to ensure that you’ve squeezed the value out of it, then set it aside and pick it up again after some time has passed. I’m doing that right now with Tom Morris’ book, If Aristotle Ran General Motors, which I read twenty years ago. I can’t wait to see how the 60 year old me reads it differently than the 40 year old version.

And it doesn’t apply just to non-fiction. I’ve gotten a ton of enjoyment from reading novels more than once. It’s amazing how much of the story you only semi-remember, and it’s fascinating to pick up on different details on the second or even third pass. A lot of people watch movies multiple times, so why not books, which are even more densely packed? I have read all 20 of Patrick O’Brian’s Master and Commander series three times, and I know I’m not done with them.

Which books have you found worth reading recently? When will you re-read them?

Moderation is dead! The only way to be heard and to have any influence in today’s world is to use extreme rhetoric. Even if you aren’t comfortable with it, you can’t beat them so it’s urgent that you join them before you get crushed! We’re in a post-truth era, which means that you have to be as forceful and hyperbolic in your claims and expression, or you are guilty of persuasion malpractice. IF YOU AREN’T OUTRAGED, YOU’E NOT PAYING ATTENTION!

Now that I got that out of my system, let me start again by saying:

Judging from our current political climate, it would seem that the use of extreme rhetoric is on the rise. You might even think that it’s the only way to get heard, so you would be forgiven for being tempted to adjust your persuasive approach. Some say we’re in a post-truth era, in which outlandish claims don’t have to be true—as long as they work. That being so, if you’re moderate and measured you will only be ineffective on behalf of your side.

Here’s the problem: the second paragraph is more credible, but the first one grabbed your attention.

That’s why it has recently been common practice in our national discourse toward extreme claims and excessive fear mongering. The other side doesn’t just disagree with us, they hate us. Their policies aren’t just misguided, they will cause an irrevocable disaster. The world is falling apart, so we have to be as forceful as possible to save it.

After a while, you just get numb to it, so they ratchet up their rhetoric even more to get past your filters. When they cry wolf so often, the townspeople put on earmuffs and go on with their lives. The problem is that when a real wolf does appear, who will listen then?

I’m not sure anything can be done about it; I certainly don’t have any answers. But it’s critical to your credibility and influence in business that you don’t let it affect the way you sell your ideas.

In fairness, there are some benefits to making extreme claims. Forcefulness grabs attention, which is why talk shows keep inviting back hedgehog pundits even after they’re proven wrong. The fox who keeps saying “on the other hand”, is politely thanked and then promptly forgotten. Plus, if you think of a proposal or an argument as the start of a negotiation where both parties eventually meet in between opening positions, an extreme claim can set an anchor that will make you look reasonable when you back off. Finally, hedges and hesitations can act as “power leaks” that detract from the forcefulness of your speech.

Yet, in negotiation an extreme opening position risks chasing away the other party by insulting them or convincing them you’re not serious. Even if they don’t walk away, they will automatically consider anything that comes out of your mouth as a worst-case or best-case scenario, and will look for contradictory evidence. The biggest risk of an extreme position is that it can trap you: once you crawl out on that limb, you’re a “loser” if you try to come back to the middle.

And there is evidence that others find a moderate level of confidence more credible. In a study done for the legal profession testing mock juries, jurors found witnesses to be more credible when they were in the middle range of confidence about their testimony. In another study, it was seen that people who are already perceived as experts actually seem more credible when they hedge their opinions a bit; it makes them appear more thoughtful.

Another piece of evidence that moderate speech may be more persuasive is the Sarick Effect, which Adam Grant discusses in his book Originals. In effect, it’s the idea that bringing out the negatives of your own idea can paradoxically make it more attractive to others, because it lowers their defenses and makes you appear more honest, among other reasons. I would think that an audience grown cynical by extreme rhetoric would at least find it refreshing.[1]

On the other hand (there I go again) , it may depend on your audience. Research shows that in general, unsophisticated audiences prefer one-sided arguments, but sophisticated audiences prefer two-sided arguments.

Moderation isn’t just about how you say it; it’s also about fairly presenting evidence. Hans Rosling ,in his excellent new book Factfulness (which incidentally sparked my idea for this post), says that you should always present a mid-forecast with a range of possible scenarios, rather than simply selecting the most extreme position As he says, “This protects our reputations and means we never give people a reason to stop listening.”[2]

So, here’s my mid-forecast: go easy on the extreme rhetoric, use only credible data, and over the long term you will protecting your reputation and ensure others keep listening. And yes, I strongly believe that!

[1] Actually, Grant made up the tern “Sarick Effect”, to make a point about how familiarity makes things more believable. That’s a topic for an upcoming post.

[2] Factfulness, by Hans Rosling, Ola Rosling, and Anna Rosling Ronnlund, p. 231.

Pick up any newspaper or browse the internet or TV and it’s almost impossible to escape the sense that the world is falling apart before our eyes. War, terrorism, violent crime, environmental catastrophe, starving children, flu epidemics, opioids, poverty. It’s not your imagination, either. A study using sentiment mining to analyze the tone of New York Times articles from 1945 to 2005 shows a significant downward trend, and I suspect it has gotten worse since then. With all that, how can you avoid being depressed and pessimistic about the state of the world?

It’s actually not that difficult, if you follow the trend lines instead of the headlines, according to a hugely important new book by Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism and Progress. Read this book if you want to be not only smarter but happier.

If you complain about the state of the world, think about it this way: if you could choose any other time in history into which to be born, which would you choose? If you chose any time before about 1800, chances are 9 out of 10 that you would be born into extreme poverty, and you would have had a 30% chance of dying in infancy. You would almost certainly have been born under an authoritarian government, and you probably would have experienced crushing hunger many times in your life.

The headlines are scary, but the trend lines clearly and unequivocally show that the world has gotten better, and continues to get better, in nearly every meaningful way. We are wealthier, healthier, safer and freer than ever in our history.

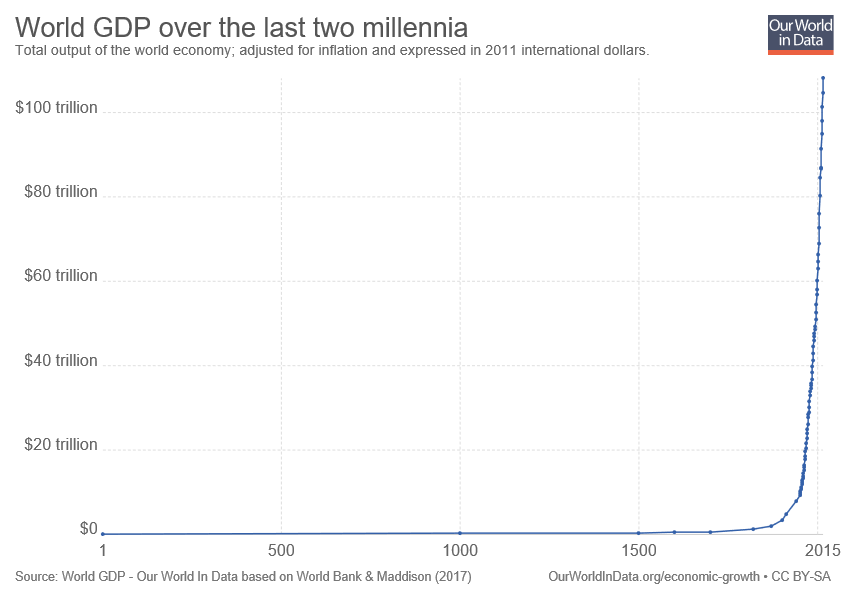

Feel free to disagree with that last statement, but you would be wrong. Just look at the data. There are 75 graphs in the book to support the case. In my view, this is the most important of all[1]:

As you can clearly see, for almost two millennia after 1 CE, world GDP barely budged, began nudging upward around 1600, and then took off exponentially beginning in the 19th century.

The other graphs in the book tell the tale of clear improvement in other aspects of human flourishing, but the reason I say this is the most important graph is twofold. First, although money may not buy happiness, it certainly makes it much easier to solve problems that cause unhappiness. It buys scientific research, technology, aid to the poor, infrastructure, and institutions, which is why life span is way up (from 29 to 71.4), poverty is way down from 90% to 10%), transportation is safer (motor vehicle accident deaths per million miles down 96%), great powers almost never go to war anymore, diseases are being eradicated, and even quality of life is rising.

Second, the chart is so absolutely unambiguous that, clearly something happened to cause what some call the Great Escape. That something, according to Pinker, was the combination of four ideals:

Reason: we must hold our beliefs accountable to objective standards. We must dare to understand.

Science: the refining of reason to understand the world.

Humanism: privileges the well-being of individuals over the tribe, race, nation or religion.

Progress: which is not merely technical, but includes intellectual and moral. (Yes, that’s right. Our IQs are actually increasing, and our attitudes toward violence, racism…are changing rapidly)

There are people who disagree with Pinker here. I’m not one of them, although I think he only got four out of five right. What’s missing is at least a chapter explicitly giving credit to free markets. The book does state that in several places, but it’s mostly just in passing. I suspect Pinker felt he was picking enough fights with the “intelligentsia” of both the left and right and decided to stay away from that live wire.

But of course it’s not all good news. We still run the risk of nuclear war, inequality, while less than it has been historically, feeds on ubiquitous media and rising expectations and continues to stoke resentment, and we face tremendous danger from climate change. But human ingenuity can solve even those difficult problems—as long as reason and science are allowed to flourish. If we concentrate on policies to keep making the pie larger instead of fighting over slices, we’ll continue to have the resources to address the significant problems we still face.

The real danger we face, and the reason I urge everyone to read this book, is that relentless pessimism can put us on course to kill the geese that keep laying golden eggs. If everyone thinks things are getting worse, they are more likely to turn to seductively simple solutions such as populism, nationalism, and religious extremism, all of which have a dampening effect on the geese.

The irony is that those who are pessimistic about the world are optimistic about themselves. Most people polled feel they will be better off in the future, but their country will be worse off. Why does this “optimism gap” exist? Part of the problem is that our standards have risen. News events that horrify us today would have gone unnoticed just several decades ago. Because bad stuff makes the news while quiet consistent improvements don’t. When’s the last time you saw a headline about 137,000 people escaping poverty yesterday? (Which would have been true every day for the past 25 years.) and of course, availability bias guarantees that we remember the sensational anomalies.

Besides, being negative makes us sound smarter. As Matt Ridley said, “If you say the world has been getting better you may get away with being called naïve and insensitive. If you say the world is going to go on getting better, you are considered embarrassingly mad…If, on the other hand, you say catastrophe is imminent, you may expect a McArthur genius award or even the Nobel Peace Prize.” [2] As Pinker puts it, optimists always sound like they’re trying to sell you something.

In that last point, he’s definitely right. I‘m a long term optimist[3], and I am trying to sell you something: buy this book, read it, and spread the news as far and wide as you can. You’ll be doing yourself, your friends, and the world a huge favor.

[1] Source: Our World in Data website. This site contains many of the same graphical arguments Pinker makes in his book and is well worth visiting.

[2] The Rational Optimist, Matt Ridley, p. 280. Also an excellent book if you want to read more.

[3] See my post: The Power of Positive Pessimism