I’m writing this article right now because I’m not allowed to do anything else.

It’s a simple and powerful productivity trick called the Nothing Alternative. You can use it when you:

- Have an unpleasant but important task

- Are trying to establish a new habit

- Are prone to procrastination

- Are easily distracted

There are only two rules. First, you have to set aside time in your schedule for the activity. Second, you don’t have to do the activity if you don’t feel like it, but you can’t do anything else during that time.

I learned about the Nothing Alternative from Roy Baumeister, in his book, Willpower. He cites the example of mystery writer Raymond Chandler, who recommended that the aspiring writer had to set aside four hours a day, during which,

“He doesn’t have to write, and if he doesn’t feel like it, he shouldn’t try. He can look out the window or stand on his head or writhe on the floor, but he is not to do any other positive thing, not read, write letters, glance at magazines, or write checks.” (p. 254)

The beauty of the Nothing Alternative is that it’s low stress and it’s binary. Since you’re not forced to write (or prospect, or take that online course you’ve been talking about forever, etc.), your brain does not automatically resist. Second, since there’s no gray area, you can’t rationalize your way out of the activity by pretending that just looking at email for a minute or two is OK, or that scanning a couple of blog posts might give you inspiration. (Although refilling the coffee mug is not only acceptable but obligatory.)

When I determined about a month ago to write daily posts and to finally finish my next book, I figured it would take 90 minutes a day, which I’ve scheduled in my calendar from 7:30 to 9:00 every workday morning that I’m not traveling. Although I haven’t writhed on the floor yet, I have looked out the window a few times, or stared blankly at a flashing cursor on a white screen for a while. But the mind needs activity, and even if I can’t think of what to write, a few minutes of boredom is enough to build up pressure that begins to express itself through the keyboard.

In my own case, I find that the Nothing Alternative is useful during the first few minutes until I get cranked up, and then sometimes after about an hour when I start to lose a bit of steam.

The immediate benefit is a dramatic increase in my writing output. But in addition, I find that crank-up time is decreasing and I can go longer without losing focus.

Incidentally, I wrote this post at 38,000 feet early on a Sunday morning, so it works anywhere. Only the view out the window is different.

We’ve all had the feeling of working hard and feeling like nothing is happening. It may be your sales prospecting efforts, or you could be trying to sell an idea internally and it’s just not getting any traction. It’s easy to think that you need to ditch your process and try something completely new. There’s a popular saying that insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. That’s a useful reminder to get people to consider new approaches, but sometimes it may actually be the wrong advice to give someone, if they’re following a sound process.

We’ve all had the feeling of working hard and feeling like nothing is happening. It may be your sales prospecting efforts, or you could be trying to sell an idea internally and it’s just not getting any traction. It’s easy to think that you need to ditch your process and try something completely new. There’s a popular saying that insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. That’s a useful reminder to get people to consider new approaches, but sometimes it may actually be the wrong advice to give someone, if they’re following a sound process.

One of the potential drawbacks to following a process is that a process tends to imply measurable forward movement, and the lack of any signs of it can be pretty discouraging.

When I was working my way through college, about the only job I was qualified for was as a laborer on home remodeling construction sites. The new guys always got handed the plum assignment of breaking up concrete slabs with a 10# sledgehammer.

The first thing you notice about reinforced concrete slabs is that they are hard. You take that first mighty swing and bring the hammer down squarely on the slab—and nothing happens.

You take another mighty swing, same result. After a few more swings, you’re already starting to feel the cramps in your fingers, the sweat is starting to drip into your eyes, and you’re maybe starting to get discouraged.

But then the next swing produces a mighty CRACK!, and a big chunk of concrete falls off. From there, the rest is fairly easy. Sure, you’re still swinging a sledgehammer in the South Florida summer sun, so maybe easy is a relative term, but at least you’re seeing results.

What’s important to keep in mind is that whether you see them or not, results are happening. The outside of the concrete may look unscathed, but the energy you are putting into it is doing something. It may seem like the last swing was the only one that mattered, but every single swing of the hammer contributed equally to the end result.

Prospecting and networking are the same way—you make the calls, send the emails, ask for referrals, and sometimes you feel like those first few swings of the hammer. But the energy you’re putting into it is doing something. The important thing is to keep swinging.

If you’re trying to master a skill, you sometimes face the same issue. When you first learn, you pick up a lot of new knowledge and skill quickly, but you will eventually hit a plateau where it seems that no matter how hard you try, you’re not getting any better. But keep putting the energy into it, and something is happening. It may not happen today, or tomorrow, but the only sure thing is that if you stop, nothing will happen.

One other thing about pounding the rock: swinging a sledgehammer is dangerous, unless you constantly keep your eye on what you’re swinging at. Keep your eyes on the process, not the prize.

Keep putting in the energy. Keep on pounding the rock.

Note: I got the idea for the title from a story about the philosophy of San Antonio Spurs coach Gregg Popovich, who based it on this quote by Jacob Riis:

“When nothing seems to help, I go look at a stonecutter hammering away at his rock perhaps a hundred times without as much as a crack showing in it. Yet at the hundred and first blow it will split in two, and I know it was not that blow that did it, but all that had gone before.”

As I mentioned in yesterday’s blog post, there are practical reasons for acknowledging the vital importance of luck in our success. One of the best reasons is that you can actually become luckier.

Luck, whether good or bad, would seem to be random by definition. But what if it’s possible to increase the odds in your favor? Are some people naturally luckier than others? Is there a science of luck? Richard Wiseman, the author of The Luck Factor, certainly thinks so.

Some people just seem to be in the right place at the right time—and vice versa—more often than others. Some people might think it’s just confirmation bias—we’ve all heard stories about someone missing the flight that crashed, but we don’t read about the poor person on standby who got put on the flight only because the other person missed it. When I met a fellow on a plane whose company turned into one of my biggest clients, that was a clear case of being in the right place at the right time.

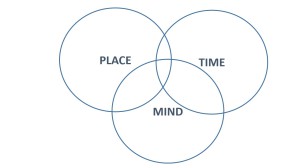

But being in the right place at the right time is not enough. The Venn diagram of Fortune has a third circle, and it’s called state of mind.

Going back to meeting people on a plane, I often fly hundreds of legs a year, and I usually don’t speak to the person sitting next to me; after training all day I’m usually not in the state of mind to be chatty. How many other potential clients have passed me by because I wasn’t in the right state of mind when the opportunity presented itself?

According to Wisemans’ research, there is a particular state of mind that will make you lucky. He has experimentally manipulated people into situations where the place and the time were right, such as planting five pound notes or potentially helpful individuals. Some people look luck straight in the face and miss it entirely, and others pick up on the opportunity instantly.

Wiseman has found that there are specific personality traits that can make you lucky. Of the Big 5 personality traits, he found three that correlate to being in the right state of mind that make you more likely to spot and exploit opportunities.

Extroversion: Although it seems unfair to introverts, extroverted people have three advantages in the luck department: they are more likely to strike up the conversation with a stranger, they have larger networks, and they tend to attract others by exhibiting more approachable body language and demeanor.

Neuroticism: Those low in neuroticism, i.e. more calm and relaxed, are more likely to take in their broader surroundings. For example, goals and focus are great, but they can also make you anxious and narrow your attention so that you miss opportunities.

In one of Wiseman’s experiments, he gave volunteers a section of newspaper and asked them to count the number of photos in the section. Almost everyone correctly counted 43 photos after about two minutes of searching, but every single person missed two messages in the newspaper, each written in large type that took up half a page.

The first was on page 2, and it read: STOP COUNTING—THERE ARE 43 PHOTOGRAPHS IN THIS NEWSPAPER.

The second message was about halfway through, and it read: STOP COUNTING, TELL THE EXPERIMENTER YOU HAVE SEEN THIS AND WIN $250.

Relax. Paradoxically, trying too hard to spot opportunities can make you less likely to do so.

Openness: People who are not open to new experiences tend to go to the same places at the same times; their circles stay small. An open mind expands the time and place circles by facilitating a greater variety in your routine, but it has the greatest effect on the size of the mind circle. When opportunity knocks, those with a closed mind peer at it fearfully through the peephole and don’t open the door.

In sum, randomness plays a bigger part in our lives than most of us credit, so why not look for ways to take advantage of it? If you have the traits Wiseman describes, lucky for you; if not, there are steps you can take to develop them. The great realist Machiavelli said, “Fortune governs one half of our actions, but even so she leaves the half more or less in our power to control.” Apparently, even the other half may also be controllable. Yes, you can get lucky if you try.

Even though I usually advocate thinking before speaking, I sometimes find words coming out of my mouth that I haven’t consciously formed—in times like that no one is more interested in what I have to say than I am. That happened to me last week when I was at lunch with a friend, and what came out of my mouth was the topic of this post (with a little more elaboration because I’ve had more time to think about it.)

Even though I usually advocate thinking before speaking, I sometimes find words coming out of my mouth that I haven’t consciously formed—in times like that no one is more interested in what I have to say than I am. That happened to me last week when I was at lunch with a friend, and what came out of my mouth was the topic of this post (with a little more elaboration because I’ve had more time to think about it.)

He asked me what I thought was the main reason I’ve been able to be successful in seventeen years working for myself. The first—and only—word out of my mouth was “luck.”

I think he was little shocked at my answer, especially since he is a relentless devourer of motivational books, which are always pounding home the message that we make our own luck. Jefferson—among others—said, “I’m a greater believer in luck, and I find the harder I work the more I have of it.”

Emerson said, “Shallow men believe in luck or in circumstance. Strong men believe in cause and effect.”

I don’t disagree with either quote. I don’t see how anyone can succeed without having a strong sense that they can control events; that’s what gives you the courage to start difficult things and the faith to keep going when unlucky things happen. And I certainly never counseled my kids when they were growing up, to depend on good luck to make it in life.

But we’re all adults now, and I think there are some good reasons to give luck its due when we consider what it takes to be successful.

The first reason for acknowledging the role that luck plays in our success is that it’s true. I was lucky to be born to middle-class parents who believed in education and were able to provide me with a stable and nurturing home. Even though I wasn’t born in the US, I was lucky that my parents brought me here when I was 14 and I could grow up in a country that rewards merit. I was lucky that I was not killed by a drunk driver a month after graduating high school, as one of my classmates was. Meeting my wife was extremely lucky, (but we’ve only been married 31 years so maybe it’s a bit early to tell…) and so on.

It’s been the same way in my business success. In my own career, chance encounters with people have played a huge part. I stumbled across one of my biggest and longest-lasting clients by striking up a conversation with the guy sitting next to me on an airplane.

Of course I’ve worked hard, and of course talking to a guy on a plane won’t help if you don’t know how to take advantage of the opportunity, but there is no denying that luck has played a big part in my success—and I suspect in yours.

Where Emerson went wrong was in thinking that strong men can’t also be shallow in their evaluation of cause and effect. We notice surface patterns but don’t spend enough time digging deeper to understand root causes, particularly when the answers might threaten our self-image. We work hard and we see results, so we make the automatic assumption that one caused the other; but just a few moment’s thought will easily bring to mind people you know who work really hard and don’t seem to get anywhere, as well as people who others who seem to have things naturally and consistently fall in their laps.

But most of my readers are more practical minded than philosophical, so just being true is not reason enough to acknowledge luck as a principal factor. Here are some practical reasons:

- It keeps you humble and grateful. Humility makes you more likeable and more likely to learn from others, and gratitude is one of the healthiest emotions you can have.

- It keeps you from making the big mistakes. Nassim Taleb, author of Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets

tells us tales of traders who outperform the market for several years in a row through sheer chance. But because they don’t know it, when luck turns against them they double down because they know their skill will pull them out, which is how they manage to wipe out years of profits in a single day.

- It puts you in a better position to recognize opportunity when you see it, which is especially helpful for people who try to control and over-plan everything. Once you recognize the role that luck plays in your life, you can actually take steps to improve your luck, which is the topic of tomorrow’s post.