The concept of value is central both to selling and to lean methods. But what is it? So, if we’re going to think about applying lean methods to selling, we must first begin with a tight definition.

One excellent definition of value comes from Michael Webb’s excellent book, Sales and Marketing the Six Sigma Way. Webb tells us that value is,

“…that which the customer will take action to get.”

This definition reminds us that the only person who can define value is the customer. So many product brochures seek to define value by product features, yet with many products, customers use only a small percentage of their features. Sometimes, vendors don’t even know why customers buy their solution. Do you? Do you understand exactly how they employ it in their daily work processes? Do you know how it prevents problems, reduces risk, or improves quality, efficiency and effectiveness? Do you know how they might be able to get more value if they use it differently?

These questions apply at the end-result level, of course: you know the customer accepts your value proposition if they buy your solution. But that’s like saying you know your team won because they outscored the opponent. The real power that this definition has to improve your sales effectiveness comes from applying it at the process level.

This past Memorial Day focused our attention on the sacrifices of the soldiers, sailors and airmen who won World War II. As the son of one of those warriors who fought in the air over Europe, I am as admiring and respectful of their achievements as anyone else. However, his B-17 bomber did not make itself, nor did the millions of tons of equipment, clothing and food that sustained them in their fight.

Those all came from the astounding ability of the American economy to convert itself to war production, as recounted in a fascinating new book, Freedom’s Forge, by Arthur Herman. That book is well worth reading for several reasons, but here I concentrate on one of the true heroes of the American war effort, Henry J. Kaiser. The two main purposes of business are to make things and to sell things, and Kaiser was a genius of both.

Kaiser’s sales skills were honed early in his life. A restless child, he quit school at 13 and was a traveling salesman at 16. His first business failed, and when he met his future wife at the age of 23, her well-off father agreed to the marriage only on the condition that he could save $1,000 and earn at least $125 a month. Kaiser took a train to Spokane Washington and began making the rounds of local businesses in search of a job. When that failed, he opted for a targeted approach and began pestering McGowan Bros. Hardware for a job. He showed up one day after a fire had swept through the business, and McGowan said, “Are you crazy? Can’t you see I’m ruined?” Kaiser offered to salvage what inventory he could and sell it. With the store back in business, within 10 months he was earning $250 a month and had bought a house for his bride.

He soon got into the roadbuilding business. One of his employees was on vacation when he overheard two men discussing a contract that was going to be awarded for a major road to Redding, California. He called Kaiser, and soon the two were on the train to the town. Unfortunately, during the trip they found out that the train they were on was an express which did not stop in Redding. Unfazed, Kaiser decided to jump from the train when it slowed down three miles outside of town. They showed up bloody and dirty but won a half million dollar contract. It probably did not hurt that when they were in the waiting room, the receptionist mentioned that her feet were cold. Kaiser went out and bought her an electric heater and never had trouble getting an appointment.

In later years Kaiser’s business grew and in partnership with five other companies built the Hoover Dam and other massive projects. By 1940, as America slowly and belatedly woke up from its isolationist dream that it could stay out of the war, Kaiser was already a famous and accomplished businessman.

1940 was a grim year for Western civilization. By the end of that year, only Great Britain held out in Europe, but they depended on a fragile lifeline of cargo ships which were being sunk three times as fast as they could be built. Existing shipyard capacity in the US was taken up by the Navy, in a belated effort to gear up for a war that the American public still believed they could avoid.

Kaiser saw an opportunity and decided to compete for a contract to build cargo ships, in spite of two minor (for him) disadvantages. The most obvious was that he had no shipyard and would be hard-pressed to tell you what the pointy end of a ship was called.

The second, ironically enough, was his reputation for superb salesmanship. Jesse Jones, one of the top gatekeepers in determining who would get the business, actually forbade his people from meeting with Kaiser alone, complaining that they would come back from meetings saying, “Mr. Kaiser is wonderful; he convinced me to give him my watch.” One secret of his sales technique was that he had excellent questioning skills. It was said that he would ask questions to get the response he wanted, and then say “That’s a great idea”.

Yet Kaiser was persistent, and had a mesmerizing ability to sell a vision and engender confidence in his ability to deliver. His motto seemed to be: “Overpromise and overdeliver.” He concentrated on the British, and brought their buyers to an empty patch of mud flats in California. The confused buyers asked, “Where are your shipyards?” Kaiser said, “Right here. Give me the contract and within months there will be a shipyard here and thousands of workers.”

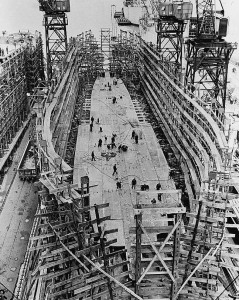

When he won the contract in December 1940, Kaiser called one of his men, Clay Bedford, and said “You’re going to build me a shipyard.” Bedford simply replied, “Where?” They had to build not only the facilities for shipbuilding, but also housing for the thousands of workers who began streaming in from all parts of the country. Starting from the mud up, the yard laid the first keel just four months later. Although they had never heard of the term “thinking outside of the box”, Kaiser, his son Edgar, and Bedford, used their unfamiliarity with shipbuilding to their advantage and revolutionized the construction process.

Kaiser knew how to spot top talent and get the utmost effort from each. Bedford and Edgar ran competing shipyards and strove to outdo each other. At the start, it took 220 days to build a Liberty ship. Both shipyards soon managed to whittle that down to less than 80 days, but still the Germans were sinking them faster than they could be built. The military clamored for faster production. By November 1942, Bedford made a special effort and built and launched the Robert S. Peary in 4 days and 15 hours, and it sailed the seas until 1963. Although that was more of a stunt than anything, it was said that they were launching ships so fast that one lady arrived at the shipyard to christen a new ship, but it was launched before she got there. She was told, “Don’t worry, Ma’am—just wait here and another will be along in a few minutes.”

In just 56 short months, Kaiser’s shipyards produced 1,490 ships.

Kaiser also had an uncanny ability to perceive a need well in advance of most people. In 1940, while most Americans were deluding themselves that they could avoid war, he realized that magnesium was going to be a metal of strategic importance, so he built four plants when everyone said he was crazy, and magnesium was delivered when it was needed in huge quantities.

Henry J. Kaiser proved on a colossal scale that the ability to anticipate a need, overcome obstacles and sell the vision, and then to deliver on the promise—are qualities that not only win sales but can help win wars.

For years, I have habitually purchased office equipment and supplies from Office Depot. Whenever I needed something, rather than comparison-shopping or thinking carefully about my choices, I would automatically get into my car and drive to their nearby store. I also have other purchasing habits as well. You’ve probably figured out by now that I buy lot of books, and my habit is to log on to Amazon, place my order, and either read it immediately on my Kindle or, if I prefer a hard copy, get it within two days with free shipping.

It’s probably the same for you, regardless of the store or the category of goods. Once you get into the habit, you tend to stick to it. And, as Charles Duhigg tells us in his fascinating book, The Power of Habit, forward-thinking businesses invest a lot of research into finding ways to change our habits to their benefit. They look for ways to create self-reinforcing habit loops, in which a cue (low on office supplies), triggers a routine (get in car and drive to store), that leads to a reward (customer satisfaction).

Yet, those who live by habits can also die by habits, if they don’t pay attention to the details that can cause their customers to stop acting automatically and take a moment to think for themselves. Another powerful psychological phenomenon is that Bad Is Stronger than Good: and one bad experience (negative reward) can undo a lot of good ones. That’s what happened to me at Office Depot today.

I went to buy ink for my printer, not because I had an immediate need, but because I received a cue in the form of a $15 coupon in the mail towards printer ink. Unthinkingly, I performed my usual routine and drove to the store, expecting my reward (peace of mind of knowing I won’t run out of ink in the middle of a major project). Instead, what I got when I came to the checkout counter was:

“I’m sorry, you can’t use this coupon.”

“Why not?”

“It’s only good for printer ink, not toner.”

“What’s the difference?”

“Ink is liquid, toner is powder.”

“You’re kidding, right?”

“No.”

“I’ll buy it somewhere else, then.”

So, I came home and activated my other habit loop, which I had never done before for office products, and logged on to Amazon. I found the brand name cheaper even than if I had been able to use the coupon; but, since I was now in a thinking mode, I decided to break another habit and buy a remanufactured cartridge, saving much, much more. Then, I figured while I was on there to look at other office supplies. It never occurred to me that I can also buy pens and paper there, too!

Companies pay the big bucks to the smart people on the front end to figure out how to entice customers, and then forget to take care of the person who actually talks to the live customer. Customer loyalty is the Holy Grail of business, yet it is one of the most fragile assets you can have, and one that retail companies entrust to poorly paid workers who receive little or no customer service training and have zero power to exercise their own judgment.

So I’m not upset with the clerk. Actually, I’m not upset at all, because I now have a new habit which will save me a lot of money; so thank you, Office Depot, for ticking me off! (And thanks for suggesting a topic for today’s blog post)

When I first learned about The Art of the Sale last Friday, I knew I had to read it. I downloaded it immediately to my Kindle and finished it on Saturday morning somewhere between California and Florida. It’s that good.

When I first learned about The Art of the Sale last Friday, I knew I had to read it. I downloaded it immediately to my Kindle and finished it on Saturday morning somewhere between California and Florida. It’s that good.

There are three key messages in this book:

The overlooked importance of selling in business and life

The book is useful for sales professionals and non-salespeople alike. I wish everyone in business who is not in sales would read this book, because it explains why nothing in business would happen without the special talents, tenacity and hard work of salespeople. Business is fundamentally about two things: a) producing goods and services and b) selling them. Guess which one of those two is almost never taught in the typical MBA program? “All over the world, from the most basic to the most advanced economies, selling is the horse that pulls the cart of business.”

In spite of this, “Many supposedly well-educated people in the business world are clueless about one of its most vital functions, the means by which you actually generate revenue. The absence of knowledge about sales has opened a class division between salespeople and the rest of business.” If you want to contribute to closing this class division, give copies of this book to your leadership team.

And it’s not just business; in life, you are always selling or being sold to. Unless you’re a hermit, most of what you do in life has to be done through others, and selling is the vehicle of interpersonal relationships.

Examining the dilemmas and tradeoffs of selling

Broughton also helps to put into perspective and clear up some misconceptions about the motivation and integrity of those who sell for a living. Of course there are dishonest and pushy salespeople, and there are those who see customers only as instruments of their own commissions. The same could be said for any other profession. Broughton examines the balance and sometime contradiction between trying to sell a product and being paid to sell it.

Selling is neutral; intention makes the difference. When you sincerely believe that what you are selling will improve the life of the buyer in some way, there is nothing wrong with trying hard to sell them on it. In the end, it’s much easier to be really good at something when it aligns with your values and your sense of meaning, and as Broughton tells us, “…the best salespeople see themselves as the means by which customers achieve their purpose.”

Portraying the qualities of great salespeople

If you’ve been in sales for any length of time you won’t learn anything new in this book, but you will be inspired and recharged by the stories of some remarkable individuals who portray the great virtues that all of us could use more of: optimism, resilience, lifelong learning, and work ethic. When you read about the pace kept by Memo, the Mexican immigrant who has created a successful construction business, you realize that you don’t work near as hard as you could. Majid in Tangier reminds you about submerging your ego, keeping quiet and learning. Although I’m not sure what its lesson is, the story of Ted Turner’s pitch to the New York advertising agency is worth the price of the book. It’s not a story I can repeat on a PG-rated blog, so you’ll have to buy the book.

The common thread in most of these stories is that selling is the “great leveler”; when you can sell, when you can apply these virtues in sufficient quantities, you can make what you want out of your life.

Ditch the Pseudo-Science

The book does contain one annoying flaw. The science parts feel as if they have been bolted on to please a marketing manager; whenever it seeks to inject science into the discussion, it’s forced, superficial and inaccurate. For example, he tries to explain one salesperson’s success using a technical explanation involving fluid intelligence and working memory that mostly points out ignorance of what those terms really mean. In another chapter, he throws in a few pages about the evolution of cooperation and altruism, and tries to connect it to the use of Salesforce.com. (May I just don’t have the fluid intelligence to understand the connection.)

Despite that last complaint, I strongly recommend this book. If you’re in sales, you will want to read it; if you’re not, you need to read it.