In 1983, Ted Kennedy accepted an invitation from Jerry Falwell, the leader of the Moral Majority, to speak at Liberty Baptist College in Virginia. It could have easily been a disaster—one of the most liberal members of the Senate speaking to a group that was actively opposed to most of what he stood for.

In 1983, Ted Kennedy accepted an invitation from Jerry Falwell, the leader of the Moral Majority, to speak at Liberty Baptist College in Virginia. It could have easily been a disaster—one of the most liberal members of the Senate speaking to a group that was actively opposed to most of what he stood for.

Kennedy may not have changed many minds that day, but he did accomplish something very important: he got his audience to listen to him.

In an earlier article, I proposed a number of ways to earn your audience’s attention. Those techniques work very well when the audience is neutral or favorable to your point of view, but when they are skeptical of your position to begin with, or downright hostile to it, the game changes. In this article, we raise the bar and consider principles for engaging your audience’s attention when they really don’t want to hear your message.

In today’s distracted world, one of the most precious commodities is your audience’s attention. When you have the floor, it can be very disconcerting to notice that most of the members of your audience seem to have their attention directed anywhere but at you. Many presenters try to counter this by asking people to turn off their phones or put their laptop screens down while they speak. Personally, I believe this is the wrong approach: it focuses on the needs of the presenter, and it’s a lazy shortcut. It works for a short time—until listeners start getting restless and distracted.

In today’s distracted world, one of the most precious commodities is your audience’s attention. When you have the floor, it can be very disconcerting to notice that most of the members of your audience seem to have their attention directed anywhere but at you. Many presenters try to counter this by asking people to turn off their phones or put their laptop screens down while they speak. Personally, I believe this is the wrong approach: it focuses on the needs of the presenter, and it’s a lazy shortcut. It works for a short time—until listeners start getting restless and distracted.

In my own training sessions I never ask people to turn off their devices, because I use them as feedback. My goal is to make what I am saying more important than what is on their screens, and I can instantly tell when I am losing someone’s attention.

In other words, I want to earn and keep their attention. Out of pure self-preservation, over twenty years of training I’ve learned and adapted many techniques which I’ve found to keep the audience’s attention.

Grab their attention

The first few seconds of any talk are prime cognitive real estate, so you have to grab their attention right from the start. The best way to take advantage of this is to do something slightly counter to expectations.

Avoid opening amenities. If you’re giving a presentation or speech, they already know who you are from the agenda or the introduction. Don’t spend time introducing yourself or thanking the audience for being there. These opening amenities are like the fine print on an ad; no one pays attention to them.

Make it relevant. Your presentation has huge opportunity costs when you add up the value of the audience’s time investment. Step 1 is to have something relevant to say, but Step 2 is just as important—tell them right up front what’s in it for them to listen. The best story I’ve heard about this is the tax accountant who told his audience of senior executives: “I realize there’s nothing particularly interesting about tax law, but I can promise you this—ten minutes of listening just might keep you out of jail.”

Surprise them. We are lulled by the familiar, but we instantly notice something that breaks the pattern. Tell them something new or different. (But keep it relevant.)

Keep their attention

Use examples from their own experience, not yours. This will require some work on your part, but it’s worth it. They will understand you better and appreciate the effort.

Be concise. Despite your best efforts, the simple fact remains that we are all squeezed for time these days, especially in an economy in which companies are trying to do more with fewer people. Don’t presume on your listeners’ time an more than you have to. Figure out what they need to know to make their decision, and leave out all the stuff that you think is cool to know.

Front-load your message. During the Civil War, journalists learned to get the gist of their story into the first paragraph, because the telegraph lines could be taken over at any time by military traffic. Your audience’s attention can also be hijacked at any time, so get to your point quickly.

Simplify. People tune out if they find your message too difficult to follow. You may be trying to cram in too much information, or your slides may be too busy. When you overwhelm their capacity to keep up, they stop running after you.

Provide structure. Think of what happens when you’re on hold on the phone or in a long line. When you don’t know how much longer it’s going to be, it can get boring very fast. Let them know where you are in the talk to keep them involved and motivated to follow you. (“Which brings me to my third point… There are three main reasons that…”)

Get them involved

Use their names. People are always attuned to their own names. It’s called the cocktail party effect. You can be talking to someone, ignoring all the conversations around you, and still hear if someone mentions your name from across the room. Plus, if they know they are going to be called on, they are more apt to stay alert.

Ask questions. Questions beggar an answer, so they are an excellent way to keep people fixed onto your topic. You can ask questions of the general group, or you can occasionally call on individuals, which will really maintain their alertness.

Make them think. I recently saw a presentation about internal cost allocation, of all things, that actually kept everyone engaged because the presenter structured it as a mystery and everyone was trying to be the first to figure out the answer.

Make it compelling

Tell stories. Stories have narrative movement; listeners are compelled to stay with them to see how they end. You see it all the time on the evening news: a piece about unemployment, for example, will feature a struggling family trying to make ends meet. Just make sure they are relevant and short.

Pay attention to your listeners. Don’t get so focused on getting out the content, or in looking at your own slides, that you don’t watch the audience carefully. Eye contact will enable you to monitor reactions and adjust as needed if you see people are losing the thread or being distracted.

Variety. For longer presentations, don’t get stuck into a predictable pattern. This applies to your voice, your slides (e.g. endless bullet lists), your evidence, etc. Move around once in a while.

Vivid imagery. Engage your listeners’ imagination with vivid imagery, whether it’s actual visuals on slides or verbal imagery.

Talk to them, not at them. It’s still a conversation. When people feel like they’re in an actual conversation with another person, it’s personal.

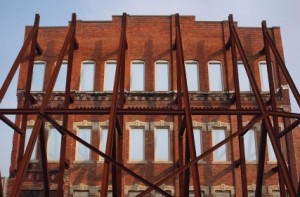

P.S. The picture above was not taken at one of my training sessions. (I think)

There was a FedEx commercial where a low-ranking employee suggests opening an online account to save shipping costs. No one responds. A few seconds later, the boss says exactly the same thing, only this time using emphatic gestures. Everyone cheers and adopts the solution. When the young guy points out that he suggested the same idea, the boss says: “But you didn’t go like this”, as he karate-chops the air.

There was a FedEx commercial where a low-ranking employee suggests opening an online account to save shipping costs. No one responds. A few seconds later, the boss says exactly the same thing, only this time using emphatic gestures. Everyone cheers and adopts the solution. When the young guy points out that he suggested the same idea, the boss says: “But you didn’t go like this”, as he karate-chops the air.

That scene may be a bit exaggerated, but the fact is that many speakers unconsciously disarm themselves by imprisoning their hands while they speak. They lose the effectiveness that gestures can contribute to the effectiveness of any presentation or conversation by supplying information, authenticity, and energy.

“Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

“Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

John Adams

Aristotle taught us that the art of persuasion rests on three legs: logos, ethos and pathos. Logos means a strong argument supported by sufficient evidence; ethos refers to personal credibility; pathos is emotional resonance.

Ethos and pathos are clearly important—most great speeches in history are engraved in our memories because they speak to our deepest feelings and values, or because they are linked to the great figures who uttered them. There will be plenty of discussions about them in this blog, but initially I’m going to stress logos because in a world of shrinking attention spans there seems to be an overemphasis on flash and superficiality, as if you can make a meal out of sizzle without the steak.