One of the most important sources of waste in communication is the gap between the words and actions, between agreeing and doing. How many times have you left a meeting room after a successful presentation, one in which you knew you presented a strong case and everyone seemed to be in agreement to proceed—and then nothing happened? Somehow when people went back to their desks and got to work, the warm glow wore off and best intentions evaporated like the morning mist.

The hard fact is that the effectiveness of a presentation isn’t measured in terms of applause or good feelings. In lean communication, the only true measure of value is substantive action that improves outcomes, and this article will examine ways to maximize the odds that your audience will follow through on agreements and intentions. As Alfred Adler said, “Life happens at the level of events, not words.”

Although this article focuses on presentations to maximize action, the ideas apply to any persuasive communication opportunity: you get a “hunting license” as an approved vendor, but no orders ensue; you get a subordinate to commit to an improvement plan, but nothing happens; you convince yourself to change, but tomorrow comes and you slip right back into old habits.

Depending on your intent for the presentation, you may not need any of the ideas in this article. What kind of action do you want? There are three ascending levels of agreement: compliance, commitment, or leadership. If it’s simply compliance you’re aiming for, such as permission to proceed and approval of resources, you don’t need to read this; but if you need their active commitment or their enthusiastic willingness to take the baton from you and lead the charge forward, read on.

What does it take?

A presentation is a vehicle for getting things done, and every vehicle needs two things to do its job: motive power and direction. In those two factors lie the keys to ensuring that you get action. Your task is to provide a reason to act, and then a clear path to follow. That’s why the first principle of lean communication is to answer “The Question”: WHAT do you want me to do, and WHY should I do it? It’s that simple, but of course it’s not always easy, so let’s break those two factors down to see what we can do to make them as strong and compelling as possible.

Motivation

Causes must precede actions, so we start with why. Most sales or internal presentations already have a solid core of sound business logic built into them, so I’m going to assume you already have that covered as your table stakes. But a business case isn’t enough, because those are real people you’re talking to. Here are three ways to make the why even more compelling.

Engage their emotions. No one ever charged up a hill waving a spreadsheet. Logic is a powerful vehicle for gaining compliance, but commitment requires a different currency. For that, you need to engage the heart as well as the mind. A wonderful story I’ve told before from John Kotter’s book The Heart of Change is about a group that had failed to get traction in its efforts to change the company’s purchasing practices despite a $1 billion business case. They finally got attention—and action—by creating a “mountain” containing 424 pairs of gloves available in their purchasing system![1] Aristotle called it pathos, and it is just as much at home in business presentations as its counterpart logos. You can beef up your pathos by adding stories, analogies, visuals and examples to your “hard facts”.

Tap into intrinsic motivation. Emotion gets attention, but it also wears off, so you also need to inspire your listeners’ intrinsic motivation, so that they will contain within themselves the motivation to act when the time comes. RAMP up your appeal by couching the action in terms of Relationships, Autonomy, Mastery or Purpose.

Make it personal. As Stalin said, “When one man dies it is a tragedy; when a million die it is a statistic,”, which is why fundraisers know that it’s far more powerful to put a face on a victim than to cite impressive statistics. In your pitch, show how the problem is affecting someone they care about—even better, tie it to the specific personal motivations of the individual decision makers in the room.

The next step to clinch their motivation is to answer why now—to show them why it doesn’t make sense to wait. Prospect theory tells us that people are more willing to act or take risks to avoid losses than to strive for gains, so make sure you bring out the consequences of not solving the problem. In fact, in my own training I observe that people tend to spend too much time on touting the benefits of the solution and not enough on the nature and impact of the problem. Especially when your audience is risk-averse, such as in a “we’ve never done it this way” mindset, you can reverse the risk by showing them how inaction is riskier than action.

Scarcity is another powerful persuader which you can invoke by putting time limits on action (as long as they are true and believable). Better yet, is to add a little competitive juice by making it clear that someone else may beat them to it.

Direction

Even when the why is obvious and undisputed, the how can trip people up, as the millions of people who want to lose weight can attest. There’s a great story in the book Switch by Chip and Dan Heath about how researchers in West Virginia solved the problem. They suggested one single change, asking people to buy low fat milk instead of whole milk. They made the point that a single cup of whole milk contains as much fat as five pieces of bacon, and suggested that people reach for the low fat milk when they went to the supermarket. This simple and clear change raised the market share of low-fat milk from 18% to 41% in the communities where it ran. The campaign worked because it made the intended action clear and easy.

Clarity sells

There are potentially dozens if not hundreds of ways to “reduce calories from fat”, but the sheer range of choice can paralyze action. It’s not only psychologists who know the value of clarity. A study of the GE Work-Out program found that, “…when ideas were presented that were focused and tangible, they were much more often accepted than vague and general recommendations.” So, for example, instead of recommending that you to be clearer in their recommendations, I might suggest that you word your ask in specific and measurable outcomes that a high school sophomore could understand and repeat back to you.[2]

Your listeners must be absolutely clear about what you’re asking them to do. This starts with being clear in your own mind about your presentation purpose before you go in, especially the specific actions you want them to take. While it should go without saying, let me be clear about one more thing: make sure there is no doubt about your ask. Make your ask up front and be sure to repeat it in a confident and assertive manner in your call to action at the end of your presentation.

Make it easy

One of the major contributors to the success of Amazon was its development and patenting of one-click ordering in 1997. You may not be able to make it that easy for others to act, but you should strive as much as possible to reduce barriers to action. Chip and Dan Heath call this tactic “shrinking the change”.

The flip side of this is to make it harder for them to resist. That’s why you should welcome tough questions and objections from the audience; in fact, if you don’t invite them you leave smoldering pockets of resistance and possibly resentment that will flare up after you’re gone.

Another tactic is to get individuals to commit publicly to act, which increases compliance in two ways. First, it puts their credibility at risk if they change their minds and don’t come through and second, it taps into the Cialdini’s consistency principle. But make sure that they commit to something specific, not a vague generality.

Give them control

Most of us hate to be sold, even if we don’t mind buying, so do everything you can to make it the other person’s idea to do what you want them to do. Here I’ll contradict slightly what I said about being very clear about your ask. Even if you’ve made an excellent case for one choice, it helps to have another possible but less attractive choice, or go one step further and use Goldilocks framing to make taking action feel just right.

So here’s my call to action for you: you can be seen as a master of getting things done, unless someone else does it before you do, so next time you present, strengthen your why, your how, or both—it’s your choice!

[1] I wonder how many of the approved vendors of those gloves would have benefited from reading this?

[2] I didn’t say SMART goals, because five adjectives is too difficult to remember—and therefore less likely to happen.

Great speakers are self-aware but not self-conscious. What‘s the difference and why does it matter?

Self-awareness is the ability to accurately monitor one’s own behavior and the effect it has on others even while doing it. It allows a speaker to critique their own performance and make adjustments as necessary, whether real-time corrections or by finding things to work on to improve their skills. Self-awareness is objective and non-judgmental. As I wrote in my last post, the best speakers over time are those who know their improvement opportunities and are eager to work on them. No one becomes a great speaker without self-awareness.

Self-consciousness, on the other hand, is one of the greatest impediments to public speaking success. It’s different from self-awareness in two ways, both of them harmful to your performance and growth as a speaker.

First, it’s an acute form of self-awareness. While it’s helpful to know how your speech or presentation is affecting the perceptions others have of you, it can become debilitating to become overly concerned about what they think. In fact, it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. For example, someone who is afraid of being perceived as nervous by the audience can tie themselves into knots of anxiety and just make themselves even more nervous.

If you’re nervous about looking nervous, keep in mind that it’s not that easy for others to read your mind. I’ve had so many participants in my sessions tell me they were extremely nervous, and I assured them that no one noticed.

That’s because you’re probably wrong about what others think of you. Most of us overestimate the extent to which people actually pay attention to us, and we usually think the worst. If you’re wearing a shirt with a stain on it, you think the whole world is laughing at you, but the fact is, they most likely don’t even notice, and even if they do, they just don’t care, and even if they care, they won’t remember it.

If you’re skeptical, try this experiment. Go to work wearing a mismatched pair of socks, and pay attention to two things: how many times you think about it during the day, and how many people actually say something to you about it. If you enjoy the experiment, you have a healthy level of self-awareness. If you’re nervous about it all day, you’re probably a little too self-conscious.

When I run my presentations workshops, I always begin the post-presentation coaching session by asking the presenter for their own assessment of how they did. It’s a sure-fire way to gauge their understanding of the elements of effective presentations, and it can also save time in the debrief. In addition, it provides a glimpse into who they are; almost invariably, they tell me something about themselves without being aware of it.

It seems like every workshop contains a bell-curve distribution of self-assessment types. Here’s a range of reactions that I get, starting at the right (good) side of the curve:

- Those who did a good job in their presentations but can list the top three things they would like to improve.

- Those who did a good job but admit they’re not aware of what they need to improve—and want to hear what coaches have to say.

- Those whose presentations needed work and know it, and want to hear how to get better.

- Those who did a good job and are therefore uninterested in hearing any improvement suggestions.

- Those whose presentations fell short of expectations and know it, but they have a ready excuse, such as not having enough time to prepare, or they always do better in front of real customers.

- Those who didn’t do a good job but thought it was great. And when they get coaching, they argue against every point that is made. They embody what psychologists call the Dunning-Kruger Effect, where those who are least skilled are most overconfident in their ability.

It would seem pointless to even waste my breath trying to coach those last two, but I always make it a point to give them very detailed feedback, even though I know they aren’t listening. That’s because without knowing it they are serving as excellent teaching tools for everyone else in the class who does want to learn. And the best part is, they don’t even know the valuable part they’re playing!

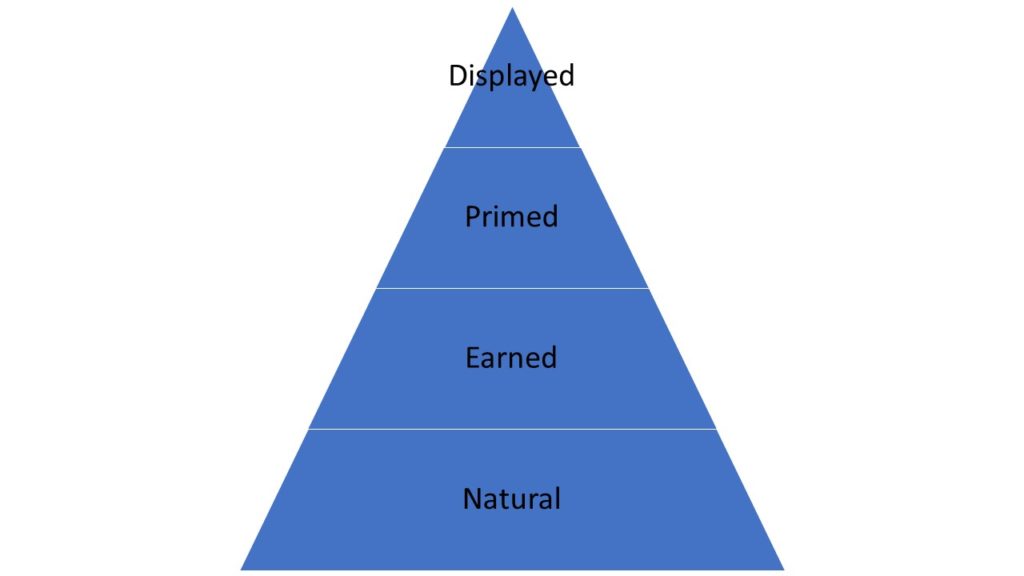

The level of confidence that you display to others can have a huge impact on your credibility and persuasiveness, but what people see is only the tip of the iceberg. While others only see what’s above the surface, that visible portion is hugely influenced by what’s beneath:

How much of what’s beneath the surface is under your control?

Natural Confidence

Some people are simply born with more confidence than others, a fact which is obvious when you compare your friends and acquaintances. They blithely charge ahead in situations where others may hang back, seemingly sure that they will get what they want regardless of the situation.

It may seem unfair, but often that confidence becomes self-fulfilling and self-reinforcing, for two reasons. First, by daring more, naturally confident people tend to win more (as long as they avoid catastrophic misjudgments), which of course confirms and reinforces their confidence. Second, the positive feedback loop is also fueled by the increased confidence of those who surround them.

It’s also backed by science; a recent study involving twins determined that self-confidence is at least as heritable as IQ, so there is clearly a “nature” component to confidence. Being extraverted also helps; being comfortable around other people and being the center of attention is a head start.

But we’re not going to spend any more time on the natural sources of confidence here, because you don’t get a Mulligan on choosing your parents. We’ll focus instead on what you can do to create and build on whatever you have naturally.

Earned confidence

Earned confidence is the most important factor under you control. It comprises two parts, general and specific. General confidence is that which you develop through your life experience and achievements, your status within the group, and your learning. You can increase your general confidence by continuously learning, building up your general competence, and successfully facing your fears by exposing yourself to stressful situations.

Specific confidence is what you have in a given situation, earned by ensuring that you have sound content and competence for that topic, that audience, and that time. When you thoroughly know your topic and you’re pretty sure you can get the other person to agree with your point of view, how can you help but feel confident? Being also promotes confidence, because the discipline and effort you put into clarifying your message will boost your confidence in that message, and in turn boost your listeners’ perception of your credibility.

Probably the most succinct statement of specific earned confidence is what Davy Crockett wrote on the title page of his autobiography: “Be always sure you’re right, then go ahead.”

Earned confidence is absolutely the most important layer of all, because it is completely in your control and it is the hardest to shake, even in the most stress-filled or intimidating situation. As Elaine Chao said, “Expertise empowers.”

If you are blessed with natural confidence and have prepared extremely well, you can stop reading now. But if you need just a little more of a boost, here goes:

Primed confidence

Even with a clearly-earned right to complete confidence, it’s still possible to be nervous despite yourself. Your conscious mind may know there’s nothing to fear, but your unconscious mind may not have gotten the memo. Besides, you can have a strong conviction that you are right and still feel a lack of confidence in your ability to get others to buy into your point of view, or you may have pre-speech jitters despite your solid grasp of your material. It’s completely natural to feel anxiety before a high-stakes meeting or big speech, and it’s just as natural to misinterpret that stress as a bad thing.

So, you may also need to get your head straight by priming your confidence level. Priming means getting yourself into the proper frame of mind to increase your felt confidence level. It prepares your unconscious mind to direct your behaviors when you speak to others, which saves you from having to spend your precious mental bandwidth thinking about your outward behavior.

This is where the psychology gets interesting. Your state of mind can influence your bodily behaviors, including posture, movement, gestures and facial expressions. But it also works in the other direction: your bodily behaviors can also influence your state of mind. Your feelings affect your actions, but your actions also affect your feelings. In fact, at any given moment, you are subconsciously reading your own body language to infer how you feel!

So, there are two general ways to boost your confidence before the meeting. You can prime your mind by changing your body, and you can prime your body by changing your mind.

Changing your body. It’s called embodied cognition: your mind takes cues from your body to help it decide how you are feeling. For example, studies have shown that simply clenching a pencil in your teeth, so that your lips are forced upwards, can make cartoons seem funnier.[1]

More importantly, acting confidently, such as taking up space and adopting “power poses”, can make you feel more confident. Doing this before your important talk boosts your confidence and actually carries over into the actual situation. Amy Cuddy and her colleagues found that the mere act of adopting a power pose for just two minutes raised testosterone levels and depressed cortisol in their test subjects. The former is associated with dominance and power and the latter is associated with stress.

They also found in a different study that subjects who adopted power poses before mock interviews were rated more highly and were more likely to be “offered the job” than those who put themselves in a closed, low power position.[2] The subtle part of the study is that there were no observable differences in behavior between the two groups during the interviews – but somehow they projected a more confident and assertive demeanor which translated to more credibility.

A power pose is one in which you open up and take up space. Stand with feet spread and place your hands on your hips with elbows out, or place both hands on a desk, more than shoulder-width apart. You can even do it sitting down; if you can get away with it, place your feet on a desk and lean back with your arms behind your head.

The important point in all of this is that you want to be fully “on” before important communications, and just like an old-fashioned vacuum tube television, you need a short warm-up period to get there.

Changing your mind. Take a minute to think back to a time when you spoke to a room full of people and you really rocked. You were totally on top of your material, you were confident and articulate, and you felt the almost scary power of having every single person tuned carefully into what you were saying. Can you picture the scene, maybe remember what you were wearing, or how you sounded? It felt good, didn’t it? You’re probably sitting up a little straighter and smiling a bit right now.

Now, imagine going through that same thought process before an important meeting or presentation. If you’ve already earned the right to be confident, it will be like lighting the afterburners on your confidence. You will feel much more confident, you will project that to the room, and your credibility will soar.

The process we’ve described is called priming, which means getting your mind into the right state before your performance. Actors do it – the best actors aren’t faking the emotions they show, they are actually feeling those emotions because they have gone through what’s called an “offstage beat”, in which they primed their minds to feel the right emotion for the scene.

There’s another equally important benefit to this. You can only feel one emotion at a time, so focusing on the right emotion will keep you from obsessing on the wrong emotion, the fear you feel before the speech.

What emotions do you want? I personally like to focus on the thrill of giving my listeners useful information that can make their lives better. Jack Welch used to prepare so much for some outside speeches that he would work himself into feeling that he could not wait to share his ideas. Think of a time when you had exciting news that you could not wait to share with someone. (In my case, I recall the time when I called my son at school to tell him that the mailman had just delivered an acceptance packet from his first-choice school.)

The great thing about priming excitement is that it feels very similar to anxiety, so it’s an easy step from one state of mind to the other.

Besides priming your mood, you can also benefit by channeling your focus. Confidence and charisma are closely related, and communication expert Nick Morgan tells us that charisma is simply focused emotion. Emotions are contagious, and someone who clearly feels an intense positive emotion is going to pass that on to anyone listening. If you can achieve that intense focus, you are going to appear supremely confident to others.

In my next post, I will focus on the visible part of the iceberg: the speech patterns and body language that affect your displayed confidence. But, if you haven’t earned and/or primed your confidence before you start, you have probably already lost.

[1] Dave Munger “Just Smile, You’ll Feel Better!” Will You, Really? http://scienceblogs.com/cognitivedaily/2009/04/06/just-smile-youll-feel-better-w-1/,

accessed May 16, 2014.

[2] Amy J.C. Cuddy and Caroline A. Wilmuth, The Benefit of Power Posing Before a High-Stakes Social Evaluation, Harvard Business School Working Paper, 2012.