The three most important persuasion tools any speaker or salesperson can use are stories, questions and visuals. Imagine the power if you could put those three together?

Last September I wrote an article about how to use questions to get the buyer to tell you their story. It works great during a sales call because it guides the listener to tell you a compelling story that makes your solution their idea. In effect, it gets your listeners to tell you what you want them to hear.

In this article, we’ll take it to another level by adding the third tool—visuals.

You can put all three tools together into an irresistible combination by using a whiteboard or flipchart to create the visuals in real time during your presentation. If you do it right, you can get the customer to show you what you want them to see.

Your eyes are—by far—more important to your presence and persuasive effectiveness than every other tool in your physical inventory, as John Travolta teaches Danny DeVito in this clip from the movie Get Shorty. By themselves, they can convey confidence, enthusiasm, credibility and personal connection.

Research has shown that listeners pay far more attention to the speaker’s eyes than to any other part of the body: 43% of the time, compared to the second-most part, the mouth.[1]

Even without the research, we instinctively know this to be true. To stress the importance of eye contact, think of what people infer about you if you don’t look them in the eyes when you talk to them. They either think you’re ignoring them, you’re lying, or you lack confidence.

There’s a good reason listeners pay so much attention to your eyes: they can be incredibly expressive and brutally honest. They are quite literally windows into your brain as you speak.

Eye contact makes you more persuasive. It’s much easier to ignore someone if they don’t make eye contact, which is why most of us tend to avert our eyes when a panhandler approaches us on the street or people sitting next to a vacant middle seat on Southwest Airlines look away when someone walks down the aisle looking for a place to sit.

It can make you seem more powerful. More powerful people look at people when talking and away while listening. I don’t advocate the latter, but the former will definitely make you seem more dominant.

It can make you more genuine because the eyes can be very expressive of genuine emotion. At least unconsciously, listeners are calibrating the emotional content of your words against the message conveyed by your eyes.

For speakers, the most important point is that eye contact can even make you more credible to people who are not the target of the gaze. Courtroom research shows that witnesses who look at the cross-examining attorney are perceived as more credible with juries. That means that you don’t have to look at everyone to be credible, but you do have to look at someone. People who suffer from presentation jitters are often advised to look over the heads of the audience; this may calm them, but it will suck the credibility right out of their message.

Finally, and just as important, eye contact also helps you maintain your audience focus and awareness. How are they responding? Are they listening, or tuning out? Do they look confused? Do they agree with your message?

With so much riding on your eyes, you can’t leave it to chance. The most important rule is to look your listeners in the eyes when you speak to them. Although that’s obvious, too many presenters violate the rule either out of sheer nervousness or by spending too much time looking at their own slides. Keep your slides uncluttered and make sure you know your material.

To ensure that you keep the visual connection, think of your listeners not as an audience, but as a group of individuals, each of whom is critically important to the success of your presentation. In most sales or internal presentations, the audience will be small enough that it’s realistic to try to make direct eye contact with everyone.

Scan the room, but make sure you look at one person for a second or two and then move on, or you’ll look like a human sprinkler. Your gaze can linger on one person immediately after making an important point, but don’t lock on for more than about two seconds or it can get uncomfortable.

You can also kick up the level of personal engagement by providing “customized eye contact”—when you make a point that is most relevant to a particular person in the room, look directly at that person. Some of the best moments in sales presentations occur when you seem to be momentarily having a private conversation with one person, and you are rewarded with a nod of agreement.

Finally, be aware that it’s possible to err on the side of too much eye contact. There are two likely scenarios where this can happen. The most common mistake salespeople make is to focus too much on the most important person in the room. Since their opinion counts for so much, it’s natural to be more concerned with their reactions, but it can cause you to ignore others in the room. The other problem is to spend too much time monitoring the reactions of the one skeptic or opponent in the room. If it’s not going well, it can make you uncomfortable or throw you off your message. Unless they have veto power over the decision, your eye time would be better invested with the other influencers in the room.

If you’re speaking to a larger audience in a ballroom-type venue, you can mentally divide the room into slices, such as left –middle-right, and then choose a friendly face in each segment to focus on. Sometimes this may not be practical, because when you’re on stage with the lights shining on you the audience may be invisible; just fake it and no one will know.

[1] Dale Leathers and Michael H. Eaves, Successful Nonverbal Communication, p. 57.

Stephen Ross, the billionaire owner of the Miami Dolphins, proved yesterday that you can be successful without being a good speaker, but also that it’s not a good idea.

Ross delivered a statement honoring retiring Dolphin Jason Taylor yesterday before the start of the game against the Jets. After fifteen spectacular years in the league, Taylor was playing in his last game, and fans were asked to be in their seats early to witness the tribute.

The “tribute” was underwhelming at best in both content and delivery. The words seem to have been put together from some prepackaged corporate template, as if all some anonymous staffer had to do was consult a checklist, fill in a few blanks, and remind Ross how to pronounce his name.

If you’re going to tell someone you appreciate them and will miss them, make it personal. Tell them specifically what you appreciate about them; don’t say something like, “you were an integral part of this organization.” (I don’t remember the exact words—and that’s the point.) Instead, tell a story about something that person did, that exemplifies a special quality they had. Or talk about what would have been different if that person had not been there.

Don’t say, “You will be missed.” Besides sounding like the most overused cliché at a funeral, it’s about as passive and impersonal as can be. Say something like, “Next year, when our defense is backed up to the goal line in a tight game, every one of us in this statdium will look for old number 99—that’s when we will all miss you.”

The only thing worse than the wording was the delivery. Ethos is the special quality of a speaker that adds or detracts from the power of the message. Ross owns the team, so he has the right to speak, but based on the jeers that followed his introduction, maybe someone more respected should have spoken. The perfect candidate would have been Zach Thomas, Taylor’s long-time teammate and brother-in-law. And if you’re going to speak from the heart, don’t read from notes. If it’s important enough to say, it’s worth a few minutes of your valuable time to rehearse and remember.

Does any of this matter? It absolutely does. Let’s look at it from a strict dollars and cents point of view. A sports team derives its value from the loyalty of its fans, those like myself who have bought season tickets for almost thirty years, and who tune in to watch the games even when the team is hopelessly inept. That loyalty is heavily driven by attachment to specific individuals who represent the organization. For the Dolphins, those individuals included Don Shula, Larry Csonka, and Dan Marino. At this moment, there is nobody associated with the team who comes anywhere close to that stature. In today’s era of interchangeable players and rotating coaching staffs, the owner may be the only enduring face of the franchise.

It would help if he could learn to speak in public.

Whether you’re trying to sell important ideas internally, or complex solutions to customers, chances are you’re going to have to convince a high-level audience at some point. To the uninitiated, this can be pretty intimidating, unless they can figure out a way to cloak themselves in that indefinable aura called “executive presence”.

On the surface, it may seem difficult if not impossible to define exactly what executive presence is. We may be left in the position of Justice Potter Stewart when he said of pornography: “I know it when I see it.”

Yet, if you define it properly, it then becomes possible to deconstruct and examine the elements that contribute to executive presence. In Aristotle’s Rhetoric, ethos was one of the three pillars of persuasive argumentation. Ethos is a quality of the speaker that determines whether the audience believes and trusts them. It is the impression created by your reputation, behavior, and appearance that adds to the persuasive power of your presentation.

Ethos is also specific to the audience; every audience has a different view of what constitutes credibility. Mitt Romney would be very credible to an executive audience, but probably not so much if he were to speak to Occupy Wall Street protesters.

Putting those two ideas together, we will define executive presence in this chapter as reputation, behavior and appearance that creates a positive feeling of credibility and trust in you among an executive audience.

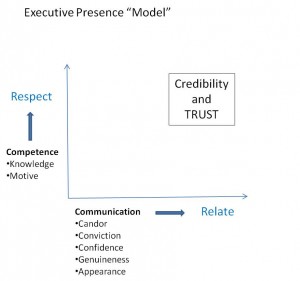

That definition allows us to create a model that captures the ideal elements of executive presence, as shown in this figure.

On one side of the chart is competence: do you know what you’re talking about, and do you apply that knowledge and ability with their best interests in mind? If you can do that, we will respect you and your message.

Competence is not enough, though, if you can’t communicate effectively. If they can relate to you personally, they are much more likely want to listen to you. Here we see five qualities that make a difference in how executives perceive you: candor, conviction, confidence, genuineness and appearance.

Just like any other model, it’s a simplification of reality, but it allows us to isolate specifics that we can work on. Let’s define each of these essentials:

- Knowledge: Do you know what you’re talking about? For many, their reputation and credentials are an advance signal of their knowledge. If someone is introducing you, have them tout your credentials, so you don’t have to come across as boastful or defensive. Otherwise, you can subtly signal your credentials through your stories, examples and questions.

- Motives: Do you have my best interests at heart? You can be the smartest person in the room but if they don’t trust your motives anything you say will be immediately suspect. The best situation is to have no motives other than the good of your listeners. If you are completely disinterested—you have nothing to gain if the listener does as you advise, your credibility goes sky-high. But of course, that’s not possible to do as a salesperson. They know you’re there to sell them something and that you benefit if they buy. So, don’t try to hide it; see #3 below.

- Candor: Do you tell it like it is? Sophisticated audiences prefer two-sided arguments, so they will appreciate a speaker who candidly discusses disadvantages and weaknesses, or who is open about their motives.

- Conviction: Do you believe it? This is probably the most important element of all in projecting credibility. Your listeners may not agree with you, but they will respect and appreciate anyone who clearly and strongly believes in the proposal they are presenting. Don’t be afraid to let your conviction show through. Conviction is not the same as passion, which can be viewed with suspicion at executive levels.

- Confidence: Are you confident? As social beings, humans are exquisitely attuned to the relative power between individuals, and confident language and demeanor are our principal tools for expressing our power, so it’s important to be aware of how your speech patterns and demeanor affect your persuasiveness. As to speech patterns, be concise and avoid power leaks, such as hedges and excessive filler words. For a confident demeanor, follow the advice your mother taught you when you were very young: “Stand up straight, look people in the eye, and smile”.

- Genuineness: Are you real? People want to relate to you as a real person. It does not mean “letting it all hang out” and being completely transparent and honest. It means presenting your best self for that particular situation. Be friendly and professional, and act like you’re excited to be there.

- Appearance: Do you look the part? Even though we’re all familiar with the old saw that you can’t judge a book by its cover, we all do. In fact, in our increasingly distracted society, we are probably less likely to take the time to look past the cover if it does not attract us. It’s the same with your presentations: the world is not a fair place, and the unfair fact is that attractive people are more likely to get their way. While you can’t control your physical looks, you can dress professionally, pay attention to your grooming, and make sure that all accessories, such as slides and handouts, are professional and well-designed.

If you can project these qualities, you should easily be able to project executive presence, even if you aren’t tall, grey-haired and square-jawed.