Have you ever shelled out extra money to buy your dog that special dog chow, the one in the commercial that shows the dogs enjoying the meaty flavor of flame-broiled filet mignon served on pure silver? You feel good about it, but Poochy doesn’t care. Poochy, if he’s like my dogs, just wants something in his dish that will fill him up—and lots of it.

Whenever you try to sell a product, service or idea to an audience, you’re probably pretty proud of what you have to offer. You’ve got a great story to tell. You work for a fantastic company. Your product is the greatest thing since cold beer. You’ve put in hours of hard work to create eye-popping slides. And best of all, you have passion.

Guess what?

They don’t care.

Your listeners don’t care that you have a great story to tell. They have seen hundreds of presentations that open with the seller’s story, complete with company history and photos of your snazzy new headquarters building. They care about their own story, and whether you can help them have a happy ending.

Your listeners don’t care that your company is fantastic. They care about whether you can make their company fantastic.

Your listeners don’t care that your product is fantastic. Well, that’s not totally true. They expect that it will be fantastic, so they first want to focus on why they might need it.

Your listeners especially don’t care about your eye-popping slides. If you can just talk to them, peer to peer, in plain language and show them how to produce eye popping results, they do care about that.

Lastly, your listeners don’t care about your passion. In fact, they may view passion with suspicion because they think it may blind you to objective truth. They care about how you can show them how to advance their passions.

Of course, I’m not advocating buying any old junk to feed your dog. As a responsible owner who loves your pet, you take your charge seriously to give them solid, healthy nutrition; you just don’t waste resources on stuff they don’t need and don’t care about.

Why should it be any different with your customers?

I had dinner the other night with some friends at a seafood restaurant. Their special for the night was the “Lazy Lobster”. I asked about the name, and they told me it was the meat from a one-pound lobster, cleaned and put into a dish so that the diner would not have to go through the trouble of picking out the meat themselves. The special was so popular that there was only one left, which my friend ordered.

He got an excellent dish; I got an excellent metaphor.

When you present to busy executives for a decision, you should serve them the lazy lobster. Too many presentations are put together like a whole lobster, where the recipient has to go through the trouble of picking the meat out themselves.

You serve the “lazy lobster” by separating out the meat is in your presentation from the shell of unnecessary detail, and then serving it to them in an appealing and easily digestible format.

You should do the thinking so that they don’t have to. I’m not implying that decision makers are lazy or stupid, but they are faced with tons of information and decision points every day, so they will appreciate the clarity provided by someone who has made it easy for them. It’s not “dumbing down”; it’s adding value by figuring out precisely what they need to know and why it’s important to them, and then laying it out in an orderly and logical manner.

Your audience is like any parent who reads these dreaded words on Christmas Eve: “some assembly required”. They will be grateful for anyone who does the work for them.

In my last post on presentations, I cautioned against taking a one-size-fits-all approach to presentations, and suggested that you should adjust the relative length of different sections depending on the audience’s relationship toward the situation. When it comes to selecting your goal for the presentation, the same idea applies.

In my last post on presentations, I cautioned against taking a one-size-fits-all approach to presentations, and suggested that you should adjust the relative length of different sections depending on the audience’s relationship toward the situation. When it comes to selecting your goal for the presentation, the same idea applies.

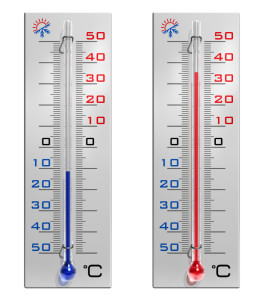

While the ideal would be to get your sale closed or your project approved in every presentation, that’s not realistic. There’s a certain thermodynamics to persuasion, in the sense that the audience’s attitude has to reach a certain temperature before they will act. The presenter is responsible for supplying the necessary heat (emotion) and light (logic) to raise the temperature.

It’s also important to keep in mind that you can sometimes cause problems by trying to raise the temperature too fast. People need time to adjust to new ideas and if they are pushed too hard too early they may shut down or strike back.

Favorable audience

A favorable audience may range from lukewarm to hot, but you’ve got to get them to boil over to take action. There are three possible goals with a favorable audience. First, you might want to strengthen their support, either to reinforce attitudes already formed or to recommit to previously agreed changes. If they’re in favor but don’t have the authority to make it happen, you have to arm them with arguments and information to sell your idea for you. If they need a push, you have to inspire them to take action. Regardless of which your goal is you should have some specific measurable agreements or actions you expect to judge whether you achieved your goal.

Neutral audience

If your audience is tepid, your goal depends on why they’re neutral. If they don’t know about the situation, you have to inform them. If they know about it but don’t see why they should care, you have to get them to agree to the consequences or costs of inaction. If they know and care, but haven’t decided on what to do or choose, your task is to gain agreement that your alternative is the best.

Unfavorable audience

When the audience is cool or even cold to your proposal, they are unlikely to become strong supporters after just one presentation. You have to be realistic in your goal: you might be able to nudge the needle into neutral, or get them to agree not to stand in your way, or at the very least continue to keep talking.

Of course, all this begs the question that you have to do some legwork before the presentation to find out the attitude of the audience. It’s further complicated when different attendees may have different views, in which case it helps to know who the decision makers and important influencers are. That’s why it helps to have a champion or coach to act as your guide. Just don’t charge in blindly with a one-size-fits-all goal.

I’ve harped on the need for rehearsal often enough in this blog, so I won’t belabor the point that I think it’s always a good idea, and the more the better.

But I also recognize that it’s not going to happen for many of you. You certainly won’t rehearse all thirty minutes of your next presentation when you:

- Are a very accomplished and experienced speaker

- Deliver roughly the same material all the time

- Have so many demands on your time

But some parts of your presentation are much more important than others, and you want to make sure they are absolutely as strong as possible. Here is a list of rehearsal priorities, in descending order of importance:

Opening: First impressions are enormously important in capturing attention and establishing your credibility. There’s never an excuse not to rehearse your opening.

Close: Almost as important as the first impression is the call to action or the feeling you leave listeners with at the end. Don’t leave this to chance by fading away at the end.

Key lines: This point applies more to an inspirational speech as opposed to a more workaday presentation. If there are one or two key lines you want the audience to remember, make sure you deliver them exactly as you intend.

Transitions: One of the best ways to look professional and in control is not having to keep looking back at your slides, and that definitely takes practice.

All the rest: I know you won’t, so nothing else to be said here.