Have you ever heard someone (perhaps even yourself) say something like, “our best-in-class quality and performance provide superior value that leads to unparalleled increases in productivity for our customers”?

Try to picture each of these words in your mind. You can’t, because they aren’t real or tangible. There’s nothing “wrong” with words like quality, performance and productivity, but you’re not doing yourself a favor if your conversations don’t use words that listeners can see, hear, feel, taste, or smell.

What do you give up when you lose concreteness?

When you give a presentation, or just have a conversation to persuade someone, you want your listeners to: listen, understand, believe, imagine and remember. Here’s how being more concrete can help:

Listen: People can’t be convinced if they don’t pay attention. Business abstractions such as quality, synergy, world-class, are used so often that we automatically block them out as meaningless buzzwords, while concrete words have the power to grab the listener by the shirt and force them to listen. You can talk about quality, or you can give a dramatic demonstration of it, by showing how beautiful or how tough your product is.

Understand: It’s tough to convince people who don’t understand your ideas. When we first learn about something, we learn about real objects, and then we gradually climb the ladder of abstraction. When everyone in the room shares a high level of knowledge, abstraction is efficient and can convey credibility. But when you’re selling an idea to someone, they typically don’t know as much as you do about it, so there’s always a danger that you will be more abstract and vague than you need to be.

Believe: One of the best ways to earn credibility is to show that you have been there and done that. Those who have, talk about real events, real people, and real things, not airy abstractions. You can mention customer complaints, or you can name a specific customer and share the language they used. Being specific is another aspect of concreteness, which is why even numbers can be used to make something more real. You can say your solution speeds up their process, or you can tell them it makes it 17% faster, which translates to $3.4 million in additional revenue.

Imagine: You are much more likely to be killed by a deer bounding across a highway than by a shark, so why do you think about sharks when you swim in the ocean but don’t worry about deer when you drive? Maybe it’s because the mental picture of having your living flesh ripped from your bones as the water turns red around you is a bit more vivid than a collision with a moving object.

People act on your ideas because they want to move away from pain or toward gain, and they are more likely to move when they can actively imagine the pain or the gain. Imagining real pains gets the motor running, and envisioning the future can get the wheels moving in the right direction. King’s Dream speech is memorable and inspiring because he helped an entire nation picture a better future. On a more mundane level, research has shown[1] that concrete and specific implementation intentions are much more likely to be carried out than general desires.

Remember: Unless someone is making an immediate decision, which is unlikely in a complex sale, they’re going to have to remember what you said when they weigh the pros and cons. They will remember things and sensations more than they will remember concepts, especially when everyone is using the same concepts (quality, value, etc.) in their presentations.

How about a concrete example?

When Boeing designed the 727 in the 1960s, they could have told their engineers to design a best-in-class, high quality and high performance airplane. Instead, they told them to build a plane that could carry 131 passengers nonstop from Miami and land on runway 4-22 at La Guardia (because it’s a short runway).[2] Besides making it clear for the engineers, do you suppose it made it easier to sell to the airlines?

Stories are all the rage in business persuasion today. Everyone loves stories. I love stories, and have written several posts about how they can be so helpful in ensuring your message gets heard, believed and remembered.

Being of a slightly contrarian frame of mind, however, I think it’s important that we remind ourselves that stories do have limits, and excessive reliance on them can weaken our persuasive efforts, especially when our listeners start probing a little deeper to find the real truth behind them.

There are three possible ways that a story can mislead:

The story may be untrue or exaggerated

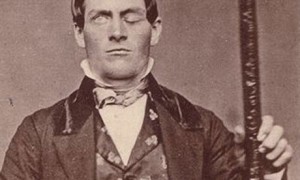

One of the best examples of this for those who are familiar with psychology is the story of Phineas Gage, the railroad company foreman in the 19th century who was impaled by an iron rod. Gage’s accident took out all or part of his left frontal lobe, and the prevalent story is that it turned him from a likeable and effective person into an unstable and angry man. Almost any book that deals with the role of emotions cites this story to show how important emotions are to a normal, stable life.

It’s a vivid and compelling story, but as this article explains, most of it is not true. Gage went on to lead a reasonably normal life, working successfully in occupations that would have punished erratic behavior. In fact, the story about the story is a cautionary tale about how a few facts can be spun into a convincing story that can be used to “prove” almost any point we want to make.

Stories are always incomplete

By design, stories simplify real life; nuance and complexity get in the way of a good story. Good storytellers know that they have to keep them short and focused, so they omit details that do not contribute to the main point. That’s not a bad thing, unless the omitted details substantially alter the conclusions drawn.

Think back to any of the three presidential debates we’ve just seen: both candidates chose stories to tell about their opponent. They didn’t have to lie (although fact-checkers on both sides will assert that the other one did), they just had to choose which facts to leave out.

The story may be true, but insufficient.

This is one of the most common ways that stories can mislead. It is especially true as the story gets more vivid or compelling. We see it all the time in the media. A savage and shocking crime feeds the perception that a much bigger problem exists, leading to a demand for more law enforcement or for new legislation. Because stories draw us in, we focus on the specific details, which distracts from the larger picture: maybe this situation is not that common.

Don’t throw out the baby with the bathwater

Please don’t assume from what I’ve written that I am against the use of stories in presenting your ideas. Stories are a powerful and indispensable tool in any persuader’s kit, but they should never be used alone. Stories and other forms of evidence work best when they support each other. Stories can dramatize statistics, for example, and statistics can prop up the truth of a story. Used together, each is much the stronger for it.

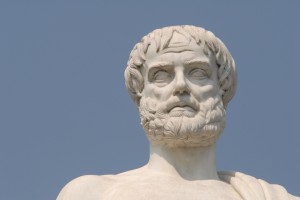

What possible use does the ancient art of rhetoric have in the twenty-first century? Although rhetoric was once an indispensable part of any real education, it began to go out of style in the 19th century, and is rarely taught in colleges today. If fact, the term itself has become mostly derogatory, signifying ornate, empty and manipulative language.

Fortunately, there are still a few people such as Sam Leith keeping the flame burning. His book, You Talkin’ to Me?: Rhetoric from Aristotle to Obama shows us that rhetoric does not have to be ornate, formal language, nor is it only empty wordsmithing. In fact, as Leith says, the only time we use rhetoric as a pejorative is when the rhetoric is obvious. Any time a person uses language to influence another, they are using the time-tested tools of rhetoric, and so much of what has been written about presentations and persuasive communication (including my own material), is a restatement or an elaboration of what Aristotle, Cicero, and Quintilian wrote so many centuries ago. The only reason we still recognize those names today is because they were so good at it, and because they knew how to pass on their knowledge to others so well.

Aristotle was the first to give us a written definition, and you can’t get any more clear or comprehensive that it: finding the available means of persuasion.

Rhetoric covers five major subjects, and they are still useful today, whether you are selling a product, trying to get an idea approved internally, or running for President.

Invention: Finding the right arguments. What is the approach that is likely to work for this audience, for this particular decision at this time? As you can see, it’s not just about what you see as the best reasons, but about what will resonate with the other person. The right approaches usually require some combination of ethos, logos and pathos. In more modern terms, we might use Daniel Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2 thinking, but we have to appeal to both. When candidates try to encapsulate their campaign into a slogan, that’s invention.

Arrangement: There are various ways to arrange your material for best effect. Aristotle preferred the simple approach of just two main parts: in the narrative, you lay out the issue at question; then in the proof you give the reasons why your idea is superior. Other manuals recommended up to six parts, but the main thing is that a clear structure helps you think clearly and makes it easy for the audience to follow.

Style: How do you say it? Style seems to command most of the attention today. Most of the negative perception around rhetoric applies to the grand style, with big words and flowery sentences. Most of us prefer speakers who are authentic and use clear and plain language. But Barack Obama showed that we can still respond to the high style on the right occasion. The most effective speakers match their style to the audience and the occasion.

Memory: in ancient times, speakers were expected to speak at length without notes, and had to learn mnemonic techniques to make sure they could remember it all. Of the five subjects, memory may seem to be the least relevant today, but the way that speakers so often use slides as a crutch suggests that they may benefit from it.

Delivery: In today’s attention-deficit world, delivery is extremely important, because it’s the only way to maintain an audience’s attention long enough to persuade them. We no longer have to worry about projecting our voices to be heard by hundreds, but we still have to appear confident, open, and in control.

I suppose you don’t have to study formal rhetoric to be an excellent speaker and persuader, but why not learn from the best?