Most consultative sales approaches, my own included, rely on the salesperson being able to sell the economic value of their solution, by connecting the solution to measurable financial and operational results. The value the customer uses to make the decision is extrinsic, and usually measurable in some way. In some cases, intangible or “soft” benefits that are not directly measurable can be important factors in the customer’s decision, even if they may need to find creative ways to justify these benefits numerically.

Most consultative sales approaches, my own included, rely on the salesperson being able to sell the economic value of their solution, by connecting the solution to measurable financial and operational results. The value the customer uses to make the decision is extrinsic, and usually measurable in some way. In some cases, intangible or “soft” benefits that are not directly measurable can be important factors in the customer’s decision, even if they may need to find creative ways to justify these benefits numerically.

But even if we include these intangibles, we’re still dealing with the WIFM model, in which people are looking for some extrinsic reward or benefit in exchange for a favorable decision. Value is expressed in extrinsic and transactional terms.

Yet people also make decisions based on values, even to the extent that they will act against their own economic best interests, or willingly undergo pain or sacrifice in pursuit of some larger goal than extrinsic reward. Persuaders who can enlist the power of values can tap into the powerful force of intrinsic motivation.

In The Art of Woo, there’s a story of how Bono approached Senator Jesse Helms to enlist his support for African debt relief so that those nations could devote more resources towards combatting AIDS. He began his pitch with a data-filled explanation of the problem, (this approach had worked very well with Bill Gates), but quickly saw that Helms was losing interest. Bono, a born-again Christian who knew Helms was also, switched to the language of the Bible and quoted Scripture to make his case. By the end of the meeting, Helms rose to his feet to embrace him, and went on to help raise $435 million for the cause.

Leaders and organizations have long used values to instill commitment instead of mere compliance: to guide and motivate their behaviors and decisions without needing to be constantly monitored, directed and rewarded. Some might say that’s the key difference between leadership and management.

As a salesperson, connecting your idea or solution to your customer’s values can be tremendously powerful: it can show a deep understanding of who they are; it can get you willing champions who will sell your idea internally when you’re not there; it can even win over those who stand to lose out in the short term if your idea is adopted. Best of all, it’s a gift to them, because it helps people bring out the best in themselves. If there is such a thing as a perpetual motion machine of persuasion, that’s it.

But values-based selling can be like TNT, very powerful yet tricky to use. It’s tricky because as an outsider it can be difficult to find out what the customer’s governing values are, and clumsiness in your approach can easily backfire on you.

You have to really understand your customer to know what they truly value. It’s not enough to go to their website and copy down their vision and values statements—too often these are the stuff of plaques and platitudes that no one takes seriously; I used to refer to them in my sales training classes until I quickly realized that most of the participants couldn’t even pick out their own corporate values statements in a multiple choice question. In some companies they’re actually held in contempt, and woe to the salesperson who tries to spout them.

In addition, trying to combine values with value can backfire on you. In Made to Stick, Chip and Dan Heath tell the story of a marketer of a fire safety video who tested an identity appeal against an incentive appeal. The first question was “Would you like to see the film for possible purchase for your educational programs?” The second question was “Would your firefighters prefer a large electric popcorn popper or an excellent set of chef’s carving knives as a thank-you for reviewing the film?” The first question received unanimous “yeses”; the second question was discontinued after receiving the first two replies: “Do you think we’d use a fire safety program because of some #*$@% popcorn popper?” Because the firefighters valued their role as safety educators, they resented the implication that they might need external rewards to recommend the film.

HOW TO SELL ON VALUES

To use values as part of your sales message without getting burned, it’s critical to know your audience and then to apply just the right touch to your message.

Know your audience: how to discover their values

- Start with their written values. Sometimes they are what people really value, and it can help to at least open the conversation and improve your questions.

- Research beyond the customer’s web site; check out articles written by others, speeches by their top executives, etc.

- Ask your champions and coaches: if you want to try something in a presentation or a sales call, run it by one of them first to see what they think.

- Ask and listen: when you’re asking your questions to uncover their business and personal goals, listen for stories, examples and words that indicate personal or corporate values. If you don’t hear any, you can probe a little deeper, by asking whya certain goal is important to them. Listen carefully for things such as:

- Why and how were previous important decisions made?

- Who are their heroes and why?

- What do they measure and reward?

- Get them out of the office. In social situations, people are much more apt to open up about their personal motivations and values.

Apply the right touch

Even if you get their values absolutely spot-on, you may provoke pushback by tying your message too explicitly. People tend to resent being reminded about their obligations to higher values from outsiders, so it’s better to get them to think of these values on their own and make the connections themselves. Fortunately, the process you go through in discovering their values has the added benefit of bringing those values to the top of their minds as you’re talking to them.

During your situation questioning, it’s appropriate to get them to talk about what’s important to them. You can ask about their business goals, and when told, go a step further and ask why a particular goal is important to them.

If you have a good enough relationship with someone, it’s easier to be more transparent in your appeal, so you can be more direct by getting your coach or champion to make the appeal for you.

I’m not an art expert, but I think it’s safe to say that painters paint the picture first and then worry about the frame. In persuasive communications, you need to do the opposite: choose the frame first and then paint your word picture. If you manage the frame, you manage the message.

A frame is simply a point of view, or a perspective to take on a particular situation. People have long known, and psychologists have recently confirmed, that changing perspective can change conclusions drawn and the choices made. In one disturbing example, even physicians were more apt to recommend a procedure with a 90% survival rate than one with a 10% mortality rate. You probably would not consider it fair if a store told you that you had to pay a surcharge for using a credit card, how we look at the decision has a significant—often decisive—effect on the final decision. Expert persuaders pay as much attention to the frame as they do to the objective facts.

Frames are so powerful because your mind doesn’t process all the millions of bits of information that simultaneously bombard your senses; it simply can’t. And, even if it could, it would not be the most efficient use of brainpower and time: our ancestors survived long enough to pass on their genes to us because in emergencies they were able to focus on a limited—but correct—set of the incoming information. When we “choose” what to attend to, we exclude a vastly larger set of information. We each see the world through a limited “window”, whether or not we’re aware of why we choose that particular point of view at the time. That’s why several people can view a scenario and come away with very different perceptions and interpretations of what happened.

So many different frames to choose from

Let’s visit the frame shop and see what a rich array of choices we have for framing our arguments for maximum persuasive effect:

Positive/negative framing: In a nutshell, people are more likely to take risks and incur costs than to achieve gains. In an example I’ve written about before, about ¾ of respondents choose one decision when it is framed one way, and ¾ choose the exact opposite decision when it is framed another way. The effect is so strong that even when I use the example in my classes, many of the participants reverse their preferences even when they know there is no objective difference! If you were mulling over an investment that could make your company more competitive, do you suppose it might make a difference if you focused on the possibility that your competitor might implement it before you do?

This doesn’t mean all your messaging should be framed in a negative way. If the other person has already decided to do something, but not necessarily what, frame the what positively—they’re much more likely to buy the 90% lean beef than the 10% fat.

Identity framing: This is one of the strongest frames because it draws on intrinsic motivation. Everyone sees themselves in a certain way, and seeks to act consistently with that picture. In his book, Primer on Decision Making: How Decisions Happen, James March tells us that when confronted with a decision, people make a rapid unconscious calculation that answers these questions: What kind of situation is this? Who am I? What does a person such as I do in this type of situation? It also works at the organizational level. Last year, when I had a billing dispute with the local hospital authority, I quoted from their values statement on their web site in my letter to the CEO, and got immediate and complete satisfaction.

Fairness framing: The need for fairness is so ingrained in our psyches that we will often hurt ourselves just to punish someone we perceive as acting unfairly. But what is perceived as “fair” is extremely subjective, as this scenario illustrates. You’re thirsty while sitting on the beach on a hot day. Your friend offers to pick up a beer for you at the swank beach-side hotel bar a block away. How much would you be willing to pay for the beer? What if he was going to buy the beer at a run-down grocery store? Would that change how much you’re willing to pay? Most people would pay $5 or more in the first instance, but not above $2 in the second. Keep in mind that it’s the same beer, and they are going to drink it in the same place, but for some reason the higher price seems fair in one scenario but not the other.

Goal framing: There’s an old saying that where you stand on an issue depends on where you sit. The people you are trying to persuade will evaluate your message in relation to the goals they are trying to accomplish. Suppose you are selling an idea that will reduce your customer’s cost of goods by 5%. How would you position it? Most people in my classes tell me they would stress the impact of cost savings on the bottom line. But if the company’s stated business strategy is to increase market share, the more effective frame might call for applying the cost savings to price reductions, and this would change the entire focus of your sales strategy, including who you approach.

In the interest of brevity, I’ll cover several other excellent frames in a future article, including analogies, narratives, and contrast effects, so for now, let’s consider what this means to you as salespeople and/or general persuaders.

With so many different frames to choose from, how do you figure out the best approach? First, you have to know your audience so well that you can figure out how they’re currently framing the decision and which frame will most resonate. If they match, great—express your idea within that frame, if possible. If they don’t, figure out how to change their frame. Once you’ve selected your frame, that’s when you paint your word picture: just make sure everything you say is relevant and consistent within that frame.

One of the most widely-held beliefs about presentations and about learning is the idea that people have a preferred learning style—auditory, visual, or kinesthetic—so students learn more when the lesson is delivered in their learning style. A study cited in yesterday’s Wall Street Journal found that 94% of secondary school teachers they surveyed believed this is true.

And it’s not just teaching—a lot of sales experts tell us that we can sell more by using this idea: “Let’s see what the numbers look like. How does that sound to you?” (Full disclosure: I used to teach the idea in my own sales training, until I saw the science.)

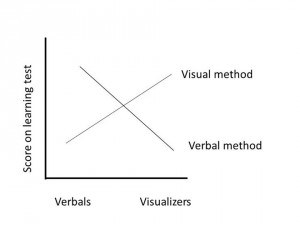

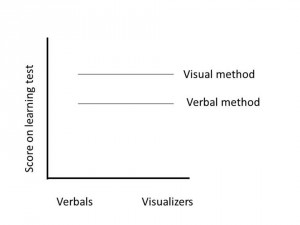

Here’s a neat little experiment and accompanying visual that Richard Mayer reports in his book, Applying the Science of Learning. They first asked students a questionnaire to have them self-assess whether they were visual or verbal learners, and the strength of their preference. (e.g. “strongly more verbal than visual” compared to “slightly more visual than verbal”). They then taught a lesson to two randomly chosen groups, one in a verbal style and one in a visual style.

If the phenomenon does work, you would expect results to look something like this:

Instead, this is what the actual results looked like:

The first conclusion that can be drawn from these results is that even if Dick sees himself as visual, and Jane considers herself to be a verbal learner, they both learn the same amount, under either teaching style.

The second point is that the visual method results in greater learning, regardless of personal preference. As you can see, we are all visual learners.

Why should a salesperson care about this? There’s enough to keep track of in a sales conversation without spending valuable bandwidth worrying about the customer’s learning style and trying to change pick the right word to suit. Forget these tricks, and focus instead on sincerely understanding the customer’s needs and motivations, and on clearly explaining the value you bring.

I trust you hear my message loud and clear, that you see what I mean, and that you can wrap your arms around this concept.

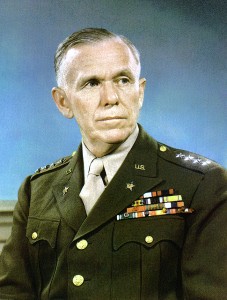

On May 13, 1940, as the Western front was reeling under Hitler’s blitzkrieg attack on France and the Low Countries, the United States had a small third-rate army, equipped with obsolete weapons. The new Army Chief of Staff, George Marshall, was trying to change that, but President Roosevelt wasn’t buying.

That morning, Marshall accompanied Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, according to the story as told by Thomas Ricks in The Generals: American Military Command from World War II to Today, to the White House to make the case for a major increase in spending to build up the military. Roosevelt made it clear that he did not want to talk to them, and after Morgenthau spoke in support of the measure, Roosevelt cut him off and said, “Well, you filed your protest.”

Morgenthau then asked the President to listen to Marshall, but FDR said, “I know exactly what he would say. There is no necessity for me to hear him at all.” Others in the room sat quietly, offering no support. As the meeting ended, Marshall approached Roosevelt’s desk and said, “Mr. President, may I have three minutes?”

The President assented, and then began to say something else, but Marshall, afraid that he might not get to speak, spoke right over him. He spoke rapidly, full of facts and figures, saying, “If you don’t do something…and do it right away, I don’t know what’s going to happen to this country. You have got to do something, and you’ve got to do it today.”

At this point, he had FDR’s full attention, and he went on: “We are in a situation now where it’s desperate. I am using the word very accurately, where it’s desperate.”

It must have been a powerful presentation, because the next day, Roosevelt asked Marshall for a list of what the military needed.

What can we learn from this extremely short but momentous speech? That sometimes it is possible to dramatically alter the listener’s attitude and position quickly if that’s the only chance you have. You too, can pull off this feat, as long as you have:

Command of the facts: It begins with content: your proposal has to be grounded in reality, and you must have the facts to back up your position. You must command your material so well that without overwhelming the listener with detail, you leave no doubt that you have all the details if needed. Besides being convincing, facts also provide a face-saving way for the listener to change his mind. When it’s about opinions, it’s hard to change someone’s mind because it can get personal.

Conviction: Conviction is not the same as passion, which is easily dismissed by the listener as purely emotional. Conviction comes from a solid foundation of thought, and the deep belief that your cause matters. It certainly contains a strong core of emotion, but that emotion may actually be more powerfully expressed by keeping it in check.

Courage: It takes tremendous guts to stand up to the President of the United States, but Marshall had the character and devotion to duty that in effect left him with little choice. But the collateral benefit of having the courage to state the truth to power, even when it can be personally very costly, is that it can confer tremendous credibility.

One final thought: Marshall already had a reputation in the Army for his ability to boil down complex issues to succinct statements. It was a skill he had honed over years, and it paid off for his country when it was needed most.