We’ve all been on the receiving end of long and convoluted explanations. We ask someone a simple question and get a dissertation in response. When it happens, we get impatient, interrupt, look for a graceful way out, while the oblivious talker merrily keeps right on going. We often leave those conversations feeling like we know less than we did when we began.

We’ve all been on the receiving end of long and convoluted explanations. We ask someone a simple question and get a dissertation in response. When it happens, we get impatient, interrupt, look for a graceful way out, while the oblivious talker merrily keeps right on going. We often leave those conversations feeling like we know less than we did when we began.

This situation is far too common when experts on a particular topic explain things to others. A lot of explanations proceed like a sailboat against the wind; they tack back and forth and take a long time to reach their destination; “on the one hand, on the other hand…”

It’s bad enough to have to listen to those who talk too much, but what if you are the one on the transmitting end of those explanations?

Why it’s a problem

Short memory and attention spans. Attention spans are shorter than ever, so it’s important to get your point in as quickly as possible. Since they won’t remember every detail you told them, don’t bury your main point in interesting but irrelevant detail. It’s especially important as you talk to higher-ranking executives.

It erodes your credibility. When you talk too much, you appear insecure and unsure of yourself and your position. Most people believe, like Einstein, that if you can’t explain something simply, you don’t understand it well enough. That may not always be true, but that is the impression they get when you over-explain. Concise explanations convey confidence.

Talking past the close. When you’re trying to sell others, they generally listen until they’ve heard enough to make a decision. If you keep talking after they’ve decided to accept your idea, you run the risk of giving them a reason to change their minds.

Loss of influence. Over time, people will stop coming to you for information if it takes them too long. They’ll stop asking for your input at meetings; they’ll turn and go the other way when they see you coming down the hall.

Possible causes

You’ve learned about the topic from the ground up, so you think that’s the best way to “teach” it.

You may be more concerned about seeming smart than about the needs of the questioner. Short, simple answers don’t show how much work it took to arrive at the conclusion.

You’re passionate about the topic, and you overestimate the interest that others take in it.

Because you know so much about the topic, small differences that are inconsequential to the questioner seem major to you.

You’re not prepared. When you hear a question for the first time, your answer is always going to be a rough draft. As any writer knows, the first version that comes out of your head can always be improved.

Solutions

Know your audience. If you know why they want to know, you can tailor your explanation to fit. It does not hurt to simply ask them why they want to know, or ask them a question or two to gauge their level of familiarity with the topic.

Prepare for conversations. This is related to knowing your audience, but also takes into account the specific topic and their relationship to it. Why do they care? What concerns or questions are they likely to have? What do they need to know to make the decision? If you’re giving a presentation, rehearsal helps you shave away unnecessary detail. For example, you’ve probably noticed that when you tell a story several times, it tends to get shorter.

Listen carefully. It’s hard to give just the right amount of information if you didn’t fully hear or understand the question. Give the other person your full focus. Even when speaking, you want to keep an eye on their reactions. It may not be as obvious as looking at their watch, but you can generally tell when you’re giving them more than they need.

Think briefly before opening your mouth. You’re not on a game show, where you have to answer as quickly as possible. Because you can think much faster than you can talk, even a very brief pause can help you compose your thoughts and formulate a shorter and better explanation.

Start with the headline. Make your explanations like a newspaper article. Give them the gist of the entire story in your opening statement, and then drill deeper as needed or asked. For example, if they ask you, “Will it work?” you don’t begin by saying, “Well that’s a complicated issue. There are a lot of factors that go into an accurate answer to that question, depending on the situation…”

Instead, you can say, “In most cases, the answer is yes (or no), although there are certain factors which might affect that.” By putting out qualifiers like in most cases, you signal to the other person that there are nuances they might want to explore further, but the choice is theirs.

Go for quality over quantity. As Churchill said, you should treat your facts like cigars: Choose only the strongest and the finest. One strong reason to do something is better than one strong reason plus three weaker reasons. You can keep the weaker reasons in reserve, and send them in only if needed.

Be as precise as necessary, but not more so. It’s better to be roughly right than precisely ignored.[1]

[1] Is there ever a time for long explanations? Of course: when the other person asks for it, or when they are about to make a decision based on dangerously incomplete information. The first one is easy, the second is a judgment call you need to make.

My favorite quote from Stephen Covey’s book is also probably his most famous: “Seek first to understand, and then be understood.” It was the fifth habit in his classic book, but it was in his own estimation the most important one of all in terms of interpersonal relationships.

My favorite quote from Stephen Covey’s book is also probably his most famous: “Seek first to understand, and then be understood.” It was the fifth habit in his classic book, but it was in his own estimation the most important one of all in terms of interpersonal relationships.

Yet most people stress the first half of the quote and treat the second half as filler. Even Covey devoted only two pages in a 22 page chapter to that side of his principle.

My point is not to downgrade the importance of “seek first to understand”. It is crucial, and anyone who has read more than a handful of the posts in this blog knows how much I stress the idea of outside-in thinking.

But…if you make a living by persuading others (and who doesn’t?), you don’t get paid for understanding people; you get paid for being understood. Understanding is crucial, but it’s not enough. Unless you can use that understanding to increase the chances that they will understand you, you haven’t gone far enough.

Some fascinating research cited in Dan Pink’s To Sell Is Human indicates that radiologists are far more meticulous and accurate in reading CT scans when there is a picture of the patient attached to the scan. No one is saying that radiologists don’t care about their patients, but somehow the simple reminder that they are looking at unique individuals unconsciously influences the way they approach their task. In the same way, I would submit that just making the effort to understand the person you’re trying to influence can unconsciously make you a more effective communicator. But there are also conscious ways that you can use your understanding to improve your chances of being understood:

Be clear, concise and candid: When you have something to say, say it—don’t beat around the bush. Lower the cost of figuring out what you’re trying to say, by speaking simply, avoiding big puffed-up words, using appropriate analogies, stories, and visuals. Focus on the why and the so what, and omit technical detail where possible.

Being concise aids clarity by forcing you to strip out anything that is not essential, and has the added benefit of making sure your message fits into today’s shrinking attention spans.

Taking the time and making the effort to understand someone else’s point of view will usually get them to open up more to you. You now have the obligation and the right to open up to them.

Customize: If you take the time to really listen and understand where the other person is coming from, and then launch into the same canned presentation that you give to everyone, you’ve just blown up any goodwill that you’ve built. You’ll look like you were merely faking it. Customization means delivering a unique message that could only pertain to them. Present the benefits of your idea in terms of their goals, aspirations and needs; use their words and their analogies; connect to what they already know.

Curtail choice: I was at a bar in Newark airport once when a man with a foreign accent asked if he could have a different side with his hamburger. The bartender said, “Of course. This is America, we have choices.” We think having a lot of choices makes us freer, but it can actually be paralyzing when we’re trying to decide. Since you’re trying to influence a decision, you need to make it easy for them to decide, by limiting the choices you present. When you don’t understand those you’re trying to influence, you tend to use a shotgun approach in hopes that something will catch their fancy. Yet we know now that too much choice reduces the likelihood someone will act or buy. Use your understanding of your listeners to present only two or three options.

Collaborative agreements: Being understood is not always a matter of expressing your thoughts in the clearest way. The strongest agreements are those that the other person decides are their own idea, when you get them to tell you what you want them to hear. You can get this done through questioning, turning your quest for understanding into a mutual process where your questions help the other person understand their own situation and motivations more clearly.

Confirm: George Bernard Shaw said “the single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.” Delivering the message is not enough. You need to confirm that it has been received in the way you intended. Sounds simple enough, but sometimes you’re afraid of what you might hear in return. I call this the 51+ rule: take at least 51% of the responsibility for your side of the communication. Don’t assume that just because you said it they understood or agreed. Test them: look them in the eyes for understanding, maybe even ask them to repeat or to confirm what they understood or what they plan to do as a result.

To summarize, let’s use Covey’s second principle: “Begin with the end in mind.” Always remember that when it comes to persuasive communication, seeking to understand is the means to your end, which is to be understood.

Everything I write and everything I teach is wrong—sometimes, under certain circumstances.

Everything I write and everything I teach is wrong—sometimes, under certain circumstances.

Often in my classes someone will say something like, “I tried that and it didn’t work.” Or, “I didn’t do it that way and I was successful.” And they are usually right when they tell me that.

There are no absolutes in persuasion, and if someone tells you there is, they are fooling themselves or trying to fool you. Communication, thinking and decision making are too varied and capricious to be perfectly predictable, because people can be so different, situations can be complex, and times can change.

That’s why honest experts allow for the occasional deviation from the rule book. Any rule that tells you what to in a specific situation is actually based on a probability. When someone says, do this in order to succeed, what they actually mean is: “If you do x, there is a ___% chance that y will happen.”[1] The corollary to that statement is that there is always a chance that y will not happen.

Of course, they’re not going to say it this way. This doesn’t necessarily mean they are purposely hiding something from you. When you teach someone, you have to give it to them in a usable format, and if you delivered all your advice and instruction in the above format, you would quickly confuse your charges, leading to little or no learning, or give them so little confidence that they would never try your advice. Besides, for many rules, the percentage probability that y will happen is high enough that the rule becomes a reliable guide for most of the situations that they will face. You would be foolish to ask for another card if you’re holding 19 in blackjack, even if it is no guarantee of winning.

So, if you’re the one learning the rules, my point is not that you should immediately question every guideline or bit of advice you read or learn in a training class, or start breaking rules just because you feel like it. Just because a rule does not work in some circumstances does not mean it’s useless. In fact, the only reliable way to develop the judgment to decide when a rule does not apply is to learn the process and the rules so thoroughly that you can recognize when an exception is called for.

Here’s why: when an unexpected question or situation comes up during a sales call or presentation, you will not have time for cautious and deep deliberation about your response. You’ll have to use your judgment and intuition; but I’m not referring to some magical, being-in-tune-with-the-universe type of gut feel. I’m referring to Gary Klein’s definition of intuition as rapid pattern recognition: expert intuition is the ability to instantly and accurately size up the situation and respond correctly. In his studies of the application of expert judgment, he found that experts don’t compare options at the moment of decision—once they’ve sized up the situation, the decision becomes obvious to them. How does an expert develop that ability? Only by becoming so deeply immersed in the fundamentals of his or her domain, which means learning and following the rules thoroughly. In other words, to know when to break the rules, you have to be thoroughly steeped in them.

Sometimes you have to break the rules, but you had better know which rule you’re breaking, why, and what the risks are. For example, you should always plan your important sales calls, but be prepared to throw away the plan and improvise on the fly when something totally unexpected happens. The customer is always right, except sometimes they are so misinformed that you have to hit them right between the eyes with the truth. Always be passionate in presenting your point of view, except when it blinds you to the legitimate perspectives of others who may not share your passion.

If you are the one dispensing the rules, realize that there is no one perfect answer that applies every single time. Have the humility and the open mind to learn from experience, especially in a fluid environment. Also, beware the curse of knowledge. There may be exceptions to the rule that are so obvious that you don’t realize they’re not obvious to other people.

The humility of acknowledging that everything you say may be wrong under certain circumstances might even help politicians on both sides of the aisle in Washington come together to produce practical and lasting legislation. It’s the only way to get things done when each side has “principles” that they hold dear.

Practical wisdom starts with accepting that every rule is wrong sometimes—maybe even this one.

[1] This is called “stripping” the claim, and it comes from Daniel Willingham’s book, When Can You Trust the Experts?

The most important principle in persuasive communication is what I call outside-in thinking: the ability to plan your approach and frame your message according to a deep understanding of how the other person thinks and how they view the situation. Outside-in communicators know that one size does not fit all; it all starts with taking the perspective of the other person.

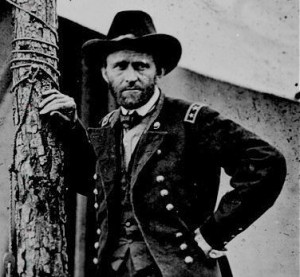

Throughout history, great generals have applied this concept by getting into the mind of their adversaries and adjust their strategy accordingly. Although “adversary” isn’t the way we want to consider those we’re trying to persuade, the principle of outside-in thinking is the same in both contexts. A story I just read about U.S. Grant in The Man Who Saved the Union, by H.W. Brands, illustrates this idea beautifully.

In February 1862, Grant commanded the Union forces that attacked the neighboring Confederate forts, Henry and Donelson, which guarded the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. Fort Henry fell relatively quickly, but Fort Donelson was a tougher nut to crack. It was nominally commanded by John Floyd, but Grant knew that he would defer to the judgment of his second in command, General Gideon Pillow. As Grant later wrote in his memoirs, he knew Pillow from their previous service together in the war against Mexico, and he was confident that he could approach aggressively against him.

Knowing they could not hold out for long, on February 15th the Confederates launched a vigorous attack against the Union forces in attempt to escape the fort. The plan came close to success, but the Union lines just managed to hold on. Fearing Union reprisals, both Floyd and Pillow—establishing a tradition that incompetent CEOs follow to this day—snuck out during the night, leaving Simon Bolivar Buckner to unconditionally surrender the fort[1].

Buckner, who had served with Grant in California, told him that if he had been in command Grant would not have gotten up close to Donelson as easily as he did. As Grant later said in his memoirs: “I told him that if he had been in command I should not have tried in the way I did.”

[1] He was pretty ticked off about the unconditional surrender demand, having banked on his long friendship with Grant and the fact that he had loaned him money to return home from California after he left the service.