Although I’ve written almost 500 blog posts about the fundamentals and nuances of persuasive communication, sometimes it’s not that complicated. Often all it takes is establishing a connection with another person based on a favorable initial impression. That initial impression can take root in less than a second and color the rest of the relationship; and because bad is stronger than good, it takes a lot of good to overcome a bad first impression.

Although I’ve written almost 500 blog posts about the fundamentals and nuances of persuasive communication, sometimes it’s not that complicated. Often all it takes is establishing a connection with another person based on a favorable initial impression. That initial impression can take root in less than a second and color the rest of the relationship; and because bad is stronger than good, it takes a lot of good to overcome a bad first impression.

So, when you shake my hand, why don’t you look me in the eyes? Why do you offer your hand perfunctorily at the same time that you are smiling at the person next to me or scanning the room to see who else is worth seeing?

My System 2 mind tells me that there are many reasons this could happen. Maybe you’re painfully shy; maybe you come from a culture that does not encourage much eye contact; maybe you just don’t like me. Any of those reasons, even the last one, I can accept. But just because you have good reasons does not mean that you have a good excuse.

That’s because my System 1 has already made up its mind, before System 2 is even aware of what’s happened. It’s telling me you’re a d__k. It’s telling me that you don’t care about me. My amygdalae are telling me to be on guard against anything you say, because on the power-warmth grid, your warmth level is at zero. If you hold it up against Aristotle’s definition of ethos—good sense, good character and goodwill—you’ve already blown two out of three.

Think of a handshake as an electrical connection; it needs eye contact to complete the circuit. While it may seem to be a waste of space and time to write about something so simple, by my own unscientific estimate, about a quarter of you need to read this and take it to heart. It takes so little time and it’s so easy to do.

Oh, and if it’s not too taxing to think about, why not add a smile?

When others judge us, they do so on to dimensions: competence and warmth. People want to know what our intentions are toward them, and whether we have the ability to follow through on those intentions. It’s self-evident that it’s best to be perceived as being in the top right of that quadrant, as both likeable and competent. All things being equal, it’s best to be liked and respected. The world’s unlikeliest purveyor of wisdom, convicted bank robber Willie Sutton, said that you can get more with a kind word and a gun than with a kind word alone.

When others judge us, they do so on to dimensions: competence and warmth. People want to know what our intentions are toward them, and whether we have the ability to follow through on those intentions. It’s self-evident that it’s best to be perceived as being in the top right of that quadrant, as both likeable and competent. All things being equal, it’s best to be liked and respected. The world’s unlikeliest purveyor of wisdom, convicted bank robber Willie Sutton, said that you can get more with a kind word and a gun than with a kind word alone.

But if you have to choose, is it better to liked or respected?

It’s a conundrum that goes back at least to Machiavelli, who addressed the question of whether it’s better for a prince to be loved or feared. Machiavelli came down firmly on the side of fear[1], which equates to competence. But modern business life isn’t quite as cutthroat as 16th century Italian politics, so let’s dig a little deeper into the question.

If you want to be credible and influential in an organization, how helpful is it to be perceived as likeable? On the surface it might seem obvious. The old saw, “You catch more flies with honey than with vinegar”, is difficult to refute. Common sense tells us that we’re more apt to listen to and give the benefit of the doubt to people who are pleasant. As I’ve learned through years of travel, when a flight is cancelled, being nice to the ticket agent is far more likely to get me a free room voucher than trying to intimidate them.

Besides common sense, there is some good evidence that being seen as likeable can make you more persuasive. Studies that have examined the credibility of witnesses in mock courtroom trials have found that more likeable witnesses were seen as more credible, although the effect was more pronounced for women. Robert Cialdini, the godfather of influence studies, includes liking as one his top influence factors.

One component of likeability is goodwill, or the perceived intent of the communicator. We are more apt to listen to and trust others when we think they have our interests at heart: (“They don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.”) Doctors who have a better bedside manner are more likely to have their instructions followed and less likely to be sued for malpractice; students learn more when they think the teacher truly cares about them; likeable political candidates are perceived as more credible.[2]

Being nice clearly pays off.

So, why did Leo Durocher say that nice guys finish last?[3] Is there something about being nice that can actually harm your credibility? Amy Cuddy of Harvard Business School says that competence and warmth can be inversely related in peoples’ perceptions. People who come across as nice may be seen as dumber. Jeffrey Pfeffer, a Stanford professor of management, says likeability is overrated, that appearing tough or even mean can improve your perceived competence. In his book Power, he cites a 1983 study that demonstrated that people who wrote negative book reviews were perceived as more intelligent than those who wrote positive reviews.

Being too nice may also hinder effective communication. It’s natural to want to be liked and to shy away from confrontation, but this can hurt you when you don’t bring out necessary truths, such as during a coaching session with a subordinate.

So, there can be a cost to being too nice. What about the other extreme, being so good that you don’t have to be nice? If you read Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs, it’s clear that he was a world-class anus, but he was so off-the-charts good at what he did that he could get away with it. Of course, that also depended on the situation. Jobs initially lost his job at Apple partly because of his personality, but then when Apple was in dire straits they brought him back. As Admiral Ernest King, who commanded US naval forces during WWII, said, “When they get in trouble they send for the sons of bitches.”[4]

If people really don’t like you, then you need to be supremely competent—and valuable—to succeed. A study involving over 50,000 leaders found that only 27, or less than 1 in 2,000, were rated in the bottom quartile of likeability and the top quartile of leadership effectiveness. Chances are that you’re not a Jobs or a King, so keep that stat in mind when you wake up on the wrong side of bed in the morning.

Which brings us to the either/or question: Is it better to be a smart jerk or an amiable dummy? Most people would say they prefer competence over likeability. But when researchers studied what people actually did when faced with a real choice to collaborate with someone informally, they found that most people chose based on likeability. In other words, likeability trumped competence. The authors of the study think it’s because most of us know it’s politically correct to say we prefer competence, so we don’t admit—even to ourselves—that we would prefer to be around nice people. But the upside to this is that while it’s not only more pleasant to deal with nice people, it can actually be more efficient, because nice people are more likely to take the time to explain things in a way that others can get it.

The other point in favor of likeability is made in this HBR article: people infer likeability much faster than competence. You can usually tell very quickly when someone has warm intentions, but it can take much longer to accurately judge their competence. So, it makes sense to lead with likeability, which also increases your chances that people will listen to you long enough to discover your competence. You can be the smartest person in the room, but if no one wants to listen, then you’re as relevant as a tree falling in the forest with no one around.

Niceness probably plays a larger part in less important decisions; when the person being influenced does not care that much about the decision, they’ll take the easy way out and decide based on cues, and liking is one of the most powerful cues of influence. But when the consequences of the decision are significant, they’ll fully engage their System 2 thinking, and focus on the evidence and the logic, which is where your competence will be fully tested. That’s where content is king, and the competent jerk will beat the amiable dummy hands-down.

What else can be said in favor of competence? To some extent, this discussion mirrors the debate over whether cognitive intelligence or emotional intelligence is more important to success. In a job like sales, you might think that EQ is more important; we all know that people buy from people they like. Except that it’s not true. Adam Grant wrote Give and Take, which is all about the virtues of being a giving person, so you would expect he would come down firmly on the side of EQ. But, as he writes in his blog, he ran two tests with hundreds of salespeople and concluded that, “Cognitive ability was more than five times more powerful than emotional intelligence.”

Or, as a lesser-known old sales saying goes, “If you want a friend, get a dog.”

So, if even in a field like sales, brains are more important than social and emotional skills, it would seem that competence wins. If you have to choose, you would probably be better off being a competent jerk than an amiable dummy.

But here’s the clincher: it’s actually a false choice. In the same article, Grant tells us that there is a strong correlation between cognitive ability and emotional intelligence. Smart people are very good at learning the skills they need to succeed, and emotional intelligence is a skill, not an inborn trait. In essence, it’s easier for a competent jerk to learn to be nice than it is for an amiable dummy to get smart. The bottom line is, it’s nice to be smart, but it’s also smart to be nice!

[1] Although even he agreed it’s best to be both, if possible.

[2] Look up McCroskey and Tevens for various papers relating to these.

[3] Actually, what he said was “The nice guys are all over there, in seventh place.” He was referring to the Giants, and where are they now?

[4] When asked if he had actually said this, he denied it but said he wished he had.

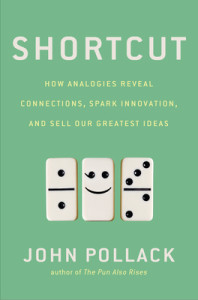

If you’re looking to make your persuasive communications more effective and efficient, a powerful tool is to master the use of analogy, as explained in a delightful book: Shortcut: How Analogies Reveal Connections, Spark Innovation, and Sell Our Greatest Ideas

If you’re looking to make your persuasive communications more effective and efficient, a powerful tool is to master the use of analogy, as explained in a delightful book: Shortcut: How Analogies Reveal Connections, Spark Innovation, and Sell Our Greatest Ideasby John Pollack.

Analogies are like the water that surrounds a fish: we don’t notice them but they are essential to the way we think and communicate. But it’s helpful to pay attention to analogies because they are powerful tools for persuasive communication; they’re essential to the way we think, learn, and react to new information.

Analogies work because our brains are hardwired to learn from experience and to make judgments with as little hard thinking as we can get away with. As we gain experience in the world, we build mental models of what works or doesn’t work, and what is good or bad. So whenever we encounter new information, we try to make sense of it by comparing it to something familiar. In essence, we choose an appropriate analogy from our vast internal database—usually instantly and unconsciously—and that colors how we react to the new information. Because there can be many familiar situations that might apply, the persuader who chooses the analogy for us creates an easy shortcut for us to take. An astute persuader chooses the best analogy; he does not leave the choice up to the recipient.

According to Pollack, there are five ways that analogies affect the persuasiveness of your ideas:

- Like a native guide in a strange land, they use the familiar to explain the unfamiliar. This is the most obvious function of analogy, and it’s particularly useful in reducing the perceived risk of new ideas.

- Like magicians who direct your attention for maximum effect, they highlight some things and hide others. They help you frame your message in the best possible light.

- They identify useful abstractions and make them concrete so that we can grasp and remember them easier. When FDR faced the difficult task of selling the American people on providing aid to Britain through Lend-Lease, he compared it to lending your neighbors your garden hose when their house is on fire.

- They tell a coherent story. In fact, an analogy is a distilled form of a story, and most stories are just extended analogies.

- They resonate emotionally. The feelings associated with the familiar transfer over to the new.

Analogies are subtle; they’re like the spoonful of sugar which makes it easier to swallow a difficult message—they help you bypass the normal reaction that people have against being told what to do. Analogies are vivid, which helps people remember your key points later on when they use the information you’ve provided to make their decision.

Most of all, analogies are powerful; once they’ve taken hold, they’re difficult to eradicate. It’s true that people who disagree with you may dispute your analogy, but there is definitely a first-mover advantage: if the analogy resonates, it’s difficult to fight it, even when they can point out flaws. An excellent example described in the book was used by John Roberts during his Senate hearings when he was nominated for Chief Justice. Roberts knew that Democratic Senators would challenge his fairness, so he opened by comparing himself to a baseball umpire; his point was that an umpire does not make the rules, he enforces them, and he does so fairly and impartially. Although then-Senator Biden pointed out that as Chief Justice, he would in fact be the one making the rules, the analogy had already taken hold. (If your opponent gets their analogy out first, it’s usually not enough to refute it. You have to fight fire with fire and come up with a better analogy of your own.)

The John Roberts example is just one of dozens that Pollack recounts in the book and which make it a pleasure to read. Read this book and you will be better able to tap into hidden superpowers of persuasion you might not even know you have.

Whether the current protests in Hong Kong turn out to be a flash in the pan that is soon squelched and forgotten, or explode into a major challenge to the Chinese government, is impossible to tell at this point. But one thing is certain, they have captured much of the world’s attention.

Improbably enough, one of the main leaders of the protests is a skinny 17-year-old kid with geeky glasses, Joshua Wong. As this article in today’s New York Times tells it, He has “been at the center of the democracy movement that has rattled the Chinese government’s hold on this city”. Ironically, at his young age Wong is already a veteran activist, who gained prominence at age 14(!) for founding a movement to fight—and defeat—the “patriotic education” that Beijing wanted to impose in Hong Kong’s schools.

I fervently hope that Joshua comes out of this alright. He has already been arrested for two days, and his fate realistically rests in the decisions of a few powerful men in Beijing.

But he has shown the incredible influence that anyone can command if they have the courage to speak out.

He has shown that leadership doesn’t have an age limit.

He has shown that leadership is not something that has to be given to you by the authorities.

How many 17-year-olds do you know that would have the courage to get up to speak in front of thousands of people, especially when stage fright may be the least of his worries? Have you ever had an idea but didn’t want to make waves? Have you ever seen an injustice but decided to go with the flow? I know I have; we probably all have. I’m just thankful that the world has people who can show us a better way.