I listened to a sermon on Sunday in which the theme was that the pursuit of money is not the surest path to happiness. The pastor’s contention was that money does not automatically lead to freedom and safety.

I listened to a sermon on Sunday in which the theme was that the pursuit of money is not the surest path to happiness. The pastor’s contention was that money does not automatically lead to freedom and safety.

It’s one of those “yes, but…” themes: no one disagrees, but no one does anything. We get messages like these all the time—from motivational speakers, from our bosses, from our parents, but very little actually changes.

If you’re the one delivering the change message, how do you get out of the “yes, but…” rut? How do you break through inertia and complacency and actually make an actual difference in someone’s behavior? One of the most common devices that speakers use is a role model which listeners can measure themselves against, and, being found wanting, act to close the gap. Role models are excellent because they show what’s possible and they provide lessons for how to improve.

But that’s where a lot of speakers and writers make a mistake: they choose the wrong role models. They are either unrealistic or too different from the target audience.

It’s tempting to choose the most prominent person in the field, which is why we use Steve Jobs, or Martin Luther King, or Winston Churchill as shining examples of the speaker’s art, and churn out books such as “The Presentation Secrets of (insert famous name here)”.

What’s wrong with using folks like them as role models? You can’t identify with them: you don’t have the resources of a multi-billion dollar corporation behind you; you will never be Prime Minister with 40 years of parliamentary speaking experience under your belt, and if you ever get the chance to address a quarter of a million people from the Lincoln Memorial, please invite me.

If you’re coaching a high school freshman to play quarterback, who’s a better role model, Tom Brady or the senior starting QB? The role model has to be better, but not so much better that he or she is totally out of reach (insert picture of a dog reaching for a treat?)

If I want to get my dog to work hard for his treat, I have to hold it just the right distance from his nose. Too low, and he snaps it up immediately; too high, and he doesn’t even bother. But if I hold it just a millimeter beyond his reach, he will jump as high as possible and won’t quit until he gets it. It’s the same way with examples. Lofty, heroic examples make for dramatic stories, but they won’t inspire emulation, because we just don’t realistically see ourselves doing the same things that the outliers do.

Role models only work if we can identify with them, and plausibly see ourselves doing the same things they do. The pastor for Sunday’s sermon used a member of a Panamanian jungle tribe as his example of someone who had very little money but lots of freedom and safety. He totally lost me, because I could not even remotely relate—I couldn’t picture myself in a loincloth, eating monkeys for breakfast. If instead he had named someone from our community who exemplified those values, I believe my mind would have been actively engaged in comparison with that person.

In their book, The Power of Positive Deviance, the authors write about their successes in driving change from within societies or organizations, such as getting villagers to improve their eating habits, or encouraging hospital staff to wash their hands. The heart of their approach is to find people under the same circumstances who are already exhibiting the behaviors that need to be copied. That’s key: it can’t come from outside “experts” because they’re not seen as relevant or realistic, but when you see people just like you who are behaving better, you know that you can do it also.

So, when you’re choosing a role model, the question is not, “Who does it best?” It’s, “Who will help your target audience to do it best”?

Since reading The Elements of Eloquence, I am seeing tropes everywhere. Unfortunately, most people seem to go for the low-hanging fruit (Boo, badly overused metaphor!), especially in the titles of blog posts.

Numbered lists are probably the most common, for three reasons:

- Someone did some research once and found that they lead to more click-throughs, so there’s at least a pseudo-scientific basis for this one.

- They give the impression of completeness.

- They promise a quick and easy read.

Alliteration is a cheap way to win one’s attention. It’s easy, and personally pleasing to peoples’ ears, even when it results in rotten writing.

Why do rhetorical questions get our attention? Is it because they spark curiosity? Do they exploit our continuous search for meaning in a chaotic world? Who knows?

William Shakespeare was perhaps the most eloquent writer in the English language, but according to Mark Forsyth, author of The Elements of Eloquence: Secrets of the Perfect Turn of Phrase

William Shakespeare was perhaps the most eloquent writer in the English language, but according to Mark Forsyth, author of The Elements of Eloquence: Secrets of the Perfect Turn of Phrase, he was not a natural genius. He achieved his eloquence by mastering—through painstaking practice, time and sheer hard work—simple, well-known tools. Well, actually they were well-known tools in his time, because back then students still learned rhetoric in schools. No one learns rhetoric anymore, which is why the world is awash in crap, cliché and corporate communication.

Why do some combinations of words sound so much better than the ordinary? In that previous phrase, everyone will recognize alliteration. I don’t think anyone knows why we like to hear words in succession that start with the same sound, but we do. You may have also recognized the use of tricolon: we like things in threes, especially when the last one is the longest.

Forsyth’s contention is that eloquence is a skill that can be improved by knowledge of the classic elements that were first catalogued by the Greeks and Romans so long ago. It’s like the difference between basic dinner fare and a gourmet meal. An amateur chef can produce a tasty meal, but a professional, with the right ingredients and long experience in combining them just so, can turn out great meals consistently. But eloquence is harder than cooking, because you have to produce a different meal every time you speak or write.

I love this book and strongly endorse it even though it contradicts two of my favorite themes.

The first is that content is king, so my first inclination was to disagree with Forsyth’s other main point: poets succeed not because they express profound ideas, but because they express ordinary ideas exquisitely. But it really is true. Sometimes we hear a phrase that just sounds so right that it’s easy to assume it’s a profound or novel thought. But when you strip away the eloquence and consider the idea, you might find it’s quite ordinary, or even nonsensical. Shakespeare could have said “your dad’s body is thirty feet deep”, but he instead said, “Full fathom five thy father lies.”

Ian Fleming deliberately gave his main character a nondescript name, yet when he said, “Bond. James Bond”, he spoke one of the most memorable lines in movie history. He used diacope, which is a verbal sandwich in which you say a word or phrase, insert an interruption, and then repeat the word or phrase.

It’s easy to assume that I have a suspicion of superficial elements that dress up an untrue or inferior idea. Yet I love a well-turned phrase at least as much as the next person.

There are three ways to read this book. First you have to read it and enjoy it. That’s easy. Then you have to study it. That’s tough but useful. Finally you can practice, practice, practice. (Parataxis with epizeuxis thrown in) You can simply enjoy it, which is easy to do because Forsyth has not only done a great job in compiling examples of the various elements, he has also come up with plenty of his own. You can also study and learn the elements so that you can recognize them when you read or hear them. Don’t worry, it won’t ruin your appreciation of good phrasing—understanding how the effect was created does not make it any less impressive. The third way is to do what Shakespeare did: actively practice. This is risky, as it’s easy to create a lot of crap that just misses the mark, but over time you might just improve the quality of your expression.

The difficulty in writing a review of a book like this is that everything sounds so pedestrian. Anything you write pales in comparison to the greats, so does that mean that one should not aspire to occasional flights of fancy? Is there a place for the elements of eloquence in ordinary business communication, or are they reserved for writers and other creative types? (Rhetorical questions)

I personally believe that while simple, plain and clear expression is perfectly fine most of the time, if you can occasionally slip in something that makes people sit up and take notice, or to repeat what you said afterward, the effects on your personal credibility and reputation may not be to your dissatisfaction. (Litotes) They make you sound smart, the elements do. (Prolepsis)

Hyperbole is something that corporate communication does a lot of, but not well. When everything is awesome or world-class, nothing is. For comparison, note how Dashiel Hammett described the skills of a detective: “(he) could have shadowed a drop of salt water from golden Gate to Hong Kong without ever losing sight of it.”

Another of my themes is the importance of efficiency and concision in speaking and writing, of cutting out unnecessary words, but religiously sticking to that would rule out merism and eliminate lines such as,

“Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon in front of them…”

which could have more concisely said by, “Cannon all around them.”

Of course, King could have shortened his speech by not saying “I have a dream…” so many times. (anaphora)

So, it’s OK to use more words than mere efficiency would dictate, but if that bothers you, you can even out the balance through zeugma (leaving out a verb) or syllepsis (using one word in more than one way), as demonstrated by,

“Sir Edward Hopeless, as guest at Lady Panmore’s ball, complained of feeling ill, took a highball, his hat, his coat, his departure, no notice of his friends, a taxi, a pistol from his pocket, and finally his life. Nice chap. Regrets and all that.”

There are two things this book may do for you–make you a better speaker, or make you a worse speaker. It could be easy to overdo it, or to get so carried away with your own wordcraft that you produce more of the aforementioned crap, which is why you should, when preparing for a speech that is one of the most important of your life, one that will determine the subsequent arc of your personal success, such as a keynote to the 2008 Democratic National Convention, or to your own CFO, who by the way despite her reputation for terseness and brevity is not immune to the power of eloquence, try out your lines on a trusted friend, one who can provide a fresh ear, sounding board, and impartial opinion. (That was hypotaxis, which has probably mercifully gone out of fashion, but was fun to write.)

It’s your choice. You can buy this book and work hard on becoming more eloquent, or you can ignore this and keep producing… (aposiopesis)

I’m going to the polls today holding my nose. After enduring months of attack ads on television and dozens of daily calls to my home phone (thank God for caller ID), it’s impossible to muster any enthusiasm or respect for either candidate for governor, or for anyone else.

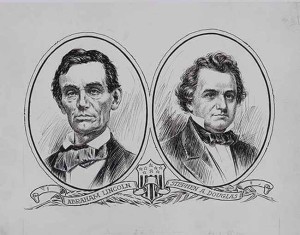

Is this the best that today’s persuasive communication can do? Billions of dollars and presumably some of the brightest minds in the business fail to produce a spark of intelligence or positivity. Our political process has devolved: through a process of survival of the nastiest, we’ve gone from the Federalist Papers and the Lincoln Douglas debates to name-calling on TV.

The scary thing is that they tell us they do this because it works. That’s scary because of what it says about us, the voters, more than what it says about them. Are we so shallow that we are susceptible to such superficial arguments? Are we so selfish that we will sell our vote for one narrow interest? Are we so distracted that we can only pay attention for thirty seconds at a time? Have we lost the skills to listen to carefully considered arguments, weigh the evidence, and form reasonable conclusions?

We complain about politicians all the time, but maybe we’re getting exactly what we deserve.