In its purest form, lean communication is about making every word count, so in that sense repetition is just a form of waste. In fact, unnecessary repetition can even subtract value. For example, the old third T: “Tell them what you told them” can sound condescending to an intelligent audience. Or if they already got your point, they’re going to get restless and tune out if you belabor it by adding yet another example.

So in its purest form, the lean communication hero would be like the guy who, when his wife complained that he never said “I love you”, replied: “I told you I loved you when I married you. If anything changes, I’ll let you know.”

If you’ve already said something once, isn’t it a form of waste to repeat it? It may seem that way, but that’s like thinking that only the last blow of the sledgehammer cracks the concrete. If you remember that the most important requirement of lean communication is to add value, you can see why repetition can sometimes be essential. Value doesn’t happen just because it’s uttered; it has to be heard, understood, agreed and remembered. Any one of those things may not happen the first time you say something: they may have not paid complete attention, they may not have fully bought into your logic, they may be thinking of the consequences of what you said, and so on. So, if you said it and it did not have its full effect, what you said only once is waste unless you repeat it as often as it takes.

When done right, repetition is the ally of persuasion because of the mere exposure effect, which says that we tend to develop a preference for things just because they’re more familiar. Familiarity seems less risky, which is important because new ideas represent change, which can be scary at first but seem less scary as we grow accustomed to it.

Churchill said it best:

“If you have an important point to make, don’t try to be subtle or clever. Use a pile driver. Hit the point once. Then come back and hit it again. Then hit it a third time – a tremendous whack.”

Going beyond day-to-day business communication, repetition is one of the most fundamental instruments of inspirational and memorable oratory. In 1940, Churchill could have said, “We shall fight everywhere we need to.” Instead, he said:

We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills.

Martin Luther King could have said: “I have a dream, and in it I see the following (bullet points)”

Instead he said “I have a dream…” eight times. Was that wasteful? He said “Let freedom ring” eight times. Was that wasteful? He said “Free at last!” three times. Was that wasteful?

So repetition has its place even in lean communication, and it’s probably more important than ever because your listeners are so easily distracted. But if you decide to use it, you need to be smart about it so you don’t irritate your audience. Keep the following two rules in mind: First, pay close attention to the reactions of your audience and offer to go over parts that seem to be missing the mark. Second, when you do repeat your point, try to say it in a slightly different way.

Did you get all that? If not, go back and read it again.

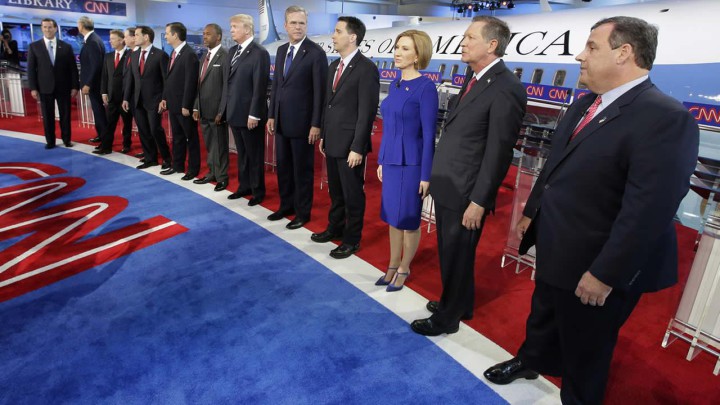

The Presidential primary races this election season have been interesting, entertaining, and hugely confounding, as persuasion experts like myself have been proven wrong time after time. I thought for sure that Donald Trump would be undone by his extremist and outlandish statements, but instead he has continued to rise in their polls and show remarkable staying power. And it’s not just Trump: his brand of rhetoric seems to have infected others who feel they have to ratchet up their remarks either in response or just to be noticed.

My hope in writing this post is that I can prevent the spread of that infection to your persuasive efforts, by explaining that what works for them will not work for you.

First, let’s look at what’s working for the candidates:

Appeal to fear and loss: We know from Kahneman’s Prospect Theory that fear appeals work, because people are more likely to take risks to avoid costs or pain than to move towards gain. That’s why there’s so much talk of what’s broken in America, how we’re under unprecedented threat that threaten our existence, and how we are losing our greatness.

Extreme opinions and expression: Political correctness has done a lot of good things for the tone and content of our discourse over the past 50 or so years, but it has also gone too far and created a climate where people can be so easily offended—or at least pretend to be, to further their own goals. So, there is an understandable pleasure that people get when they hear others say publicly what they might be thinking but would not dare say.

Ad hominem attacks: Reagan’s 11th Commandment, “Thou shalt not speak ill of fellow Republicans”, seems a quaint relic of more genteel days. Debates have turned into cage matches, with politicians attacking each other’s personality, motives, backgrounds, and even their looks. While this can actually liven up the race, it unfortunately crowds out criticism of their actual positions and prevents substantive discussion. Why take the time to patiently explain your position when it’s easier and faster to trash the competition?

Whether this brand of persuasion will continue to be effective in the coming weeks when voters actually go to the polls and make a choice is still an open question, but I’m not going to bet against it. It seems to be working really well, so why wouldn’t it work for you, in your sales or internal persuasive efforts? There are at least three good reasons:

First, others expect different things from you. In business there is still a strong expectation of professionalism and civil behavior, and violations are usually swiftly punished. Speak ill of the competition and you may not be invited back; overstate the fear appeal and you risk a backlash.

Second, you usually have to live and work closely with the people you’re trying to persuade, and scorched earth tactics that may work once will carry long term consequences. Trump can get away with saying shocking things because it’s part of his ethos; it’s what people expect from him. It’s highly unlikely that you could pull it off, and the unemployment lines are full of people whose career was undone by one careless remark. While a guy like Trump can’t lose from his tactics (he either wins the election or goes back to TV as an even bigger draw), you can.

Third and most important is the fact that the people you are trying to persuade in business are on average better educated, more intelligent, and usually have a strong stake in the decision you’re trying to influence. They are turned off by strong one-sided appeals and respond more favorably to two-sided appeals, in which you at least make an effort to understand the other side.

All this doesn’t mean that you can’t use some version—albeit much more moderate and toned down—of a couple of the candidates’ effective tactics. Here are a few suggestions.

Appeal to fear and loss: Don’t dump this as a useful persuasion tool. For example, SPIN selling approaches are powerful precisely because they bring in the Implication of inaction. But for that to work, the Implication has to be something the other person legitimately accepts, and that’s why questions rather than direct statements are the best way to bring them out.

Extreme opinions: That does not mean you should not have strong opinions or be candid when the situation calls for it. When something needs to be said, you should say it, but don’t confuse candor and directness. Candor is about having a responsibility to speak up when necessary, but directness is a choice about how to say it, and you can sometimes be more persuasive by mitigating your speech enough to make it palatable to your listener.

Ad hominem attacks: This is one tactic that I recommend you leave out of your repertoire entirely. Never do this, even when it’s being used against you. This includes trashing the competition, if you are a salesperson.

In summary, the rulebook for political persuasion may have changed, but it is still firmly in place for business and most personal persuasion, so don’t try to become a better persuader by closely following politics—spend that time reading this blog instead.

This blog post provides a holiday double-issue. It’s a Christmas gift to my readers and a suggestion for a New Year’s resolution wrapped into one.

Having trouble thinking of the perfect gift for your loved ones and your co-workers? How about a gift that won’t cost you a cent but will be priceless to those who receive it?

I’m talking about the gift of outside-in thinking.

Outside-in thinking is an attitude, an approach and a skill. It’s an attitude of taking responsibility for the other person’s outcomes, for improving their situation in some way. It’s an approach that reverses the normal thinking patterns we use when we try to sell our ideas, and it’s a skill which you can resolve to master and make a habit.

Outside-in thinking is about starting with why, by putting yourself in the other’s mind and seeing the situation from their perspective and understanding their needs and concerns. If you want to communicate effectively and improve outcomes, you need outside-in thinking because it’s not about you—it’s about your audience or your listener. You may have the idea and the impeccable logic to support it, but they have what you don’t: the power to understand, agree and act. Outside-in thinking will help you explain it in terms they can understand, give them reasons they can agree with, and move them to action.

Here’s a table that summarizes some of the major differences in attitude and behaviors between the two ways of thinking:

| Inside-out Thinking | Outside-in Thinking |

| Talking more | Listening more |

| Transmission | Reception |

| Message is the same for everyone | Customized message |

| Product-focused | Customer-focused |

| Win-lose | Win-win |

| Taking | Giving |

| Try to sound smart | Make them feel smart |

| Natural and easy | A skill that requires work |

| Show how much you know | Give them what they need to know |

| Trying to be interesting | Be interested |

| Golden Rule | Platinum Rule |

| Objections are obstacles to getting outcomes you want | Objections are opportunities to improve outcomes |

Some of the differences in the table speak for themselves, and some may require a little elaboration:

Outside-in communicators know that the quality of the reception is more important than the elegance of the transmission, so they begin their communication process from the point of view of the other person first.

Inside-out communicators craft messages and create slide decks that are one-size-fits-all. The message and its expression are the same for everyone. Outside-in communicators customize their messages and approach to the preferences and needs of the audience.

Inside-out communicators strive for win for themselves, even if it means a loss for the other party. Outside-in communicators look for ways to craft win-win solutions that increase the total value for all concerned.

Inside-out communicators worry about sounding smart by making things complicated; outside-in thinkers work hard to simplify and explain to make others smarter.

Inside-out communicators view listeners’ objections as obstacles to be overcome in order to get the outcomes they want, and they prefer to avoid them. Outside-in communicators welcome objections, because they provide a window into the other person’s needs, and provide information that may be used to work together with the other person to devise even better outcomes.

Inside-out communicators spend more preparation time fiddling with their fonts and animations than they do thinking about what the audience wants to hear.

Above all, outside-in thinking is based on the Platinum Rule, which is doing unto others as they want to be done unto, not as we want to be done unto.

Is it better to give than to receive? I think that depends on the person and the gift that is being exchanged. But the best part is that you don’t have to answer the question, because outside-in thinking is like that big-screen TV you buy for the family: it’s as much a gift to yourself as it is to the receiver.

Resolve to build your outside-in thinking muscle

To give yourself and others the priceless gift of outside-in thinking, it’s not enough to decide to change your attitude and approach—you’re going to have to work at it. So, here comes the resolution: resolve to make outside-in thinking a regular habit, and start right now.

Fortunately, outside-in thinking is not so much a skill you need to learn from scratch, as one you already have that you need to be reminded to use. It’s like listening: we all have the ability to do it well—when we remember to do it and make the effort, kind of like having a useful feature on your smartphone that you forget to use.

The holiday season is a natural time to get into the outside-in thinking frame of mind because we’re surrounded by reminders to give, but it’s so easy to revert to our old ways if we’re not constantly on guard.

There are a couple of reasons we don’t automatically apply outside-in thinking. First, we’re all selfish and egotistical, which is just another way of saying we’re human, and naturally we tend to approach things from our own perspective. Our own perspective already exists in our minds; someone else’s perspective has to be actively brought out. It’s not our default mode. Second, it’s hard work to get out of our default mode because it requires what Daniel Kahneman calls System 2 thinking, and our brains resist making any more effort than necessary.

Fortunately, research has shown that simply reminding yourself to take the other person’s perspective will make you much better at it. Reminding yourself “activates” the script in your brain. For example, when people participate in a group task, and then are asked how important their own contribution was to the final result, they usually grossly overestimate their share. But, if the same people are asked to first consider what others contributed, and then asked the question, the estimates of their own contribution drop considerably.[1]

You can prime outside-in thinking by using a brief checklist before every presentation, or even conversation or email. Ask yourself:

- What is in it for them?

- What do they know and don’t know?

- What are their needs?

- Why would they say yes or no to your idea?

- How do they like to receive information?

Print these questions and post them where you can see them. Ask—and try to answer—each of these questions the next seven times you have an important communication, and it will go a long way to turning it into a habit, and gift that will keep on giving for a long time to come.

So, to all my readers: Happy Holidays, Merry Christmas, and best wishes for a prosperous and peaceful 2016! Thank you for allowing me to present the gift of outside-in thinking.

[1] Epley, N., & Caruso, E. M. (2008). Perspective taking: Misstepping into others’ shoes. In K. D. Markman, W. M. P. Klein, & J. A. Suhr (Eds.), The handbook of imagination and mental simulation (pp. 295-309). New York: Psychology Press.

I got the idea for this post last week while I was conducting a training class on executive-level presentations. We were covering “executive presence” and I was comparing the concept to Aristotle’s idea of ethos as one of the three principal paths to persuasion. One of the participants asked me—totally out of context, I thought—what I thought of Donald Trump.

I replied that it would be unprofessional for me to share my personal opinion, as it would be irrelevant to the material being taught and could only lead to distraction (in lean terms, totally wasteful) , but I did seize the opportunity to turn the question around and ask them to apply Aristotle’s test to a real-life example, and that’s what I share here with you.

Aristotle taught us that the three available means of persuasion are logos (logic), pathos (emotion), and ethos (the perceived qualities of the speaker), and he claimed that ethos is the most important of the three. I would dispute that, because I think that any one of the three can be paramount depending on the situation; e.g. logos may come first if it’s a purely technical issue, and pathos may rule in a matter of personal taste. But, in the case of electing the leader of our nation for at least the next four years, ethos has to be first.

Ethos has to be first, if only because the product each candidate is selling is themselves. But it’s also critical because the future is so uncertain, and the most pressing issues in this election cycle may be totally forgotten by the second day after the inauguration. The emotions that people feel today—and anger appears to be the dominant emotion in the Republican primary—are poor guides to a decision with such lasting consequences, particularly as they are so easily manipulated by the political machinery. Logos is out as of now because at this stage in the primary cycle nobody listens to detailed policy prescriptions anyway.

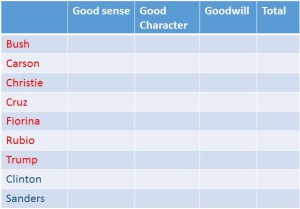

So, how do you measure ethos? Although you probably already have a gut-level feel of where you would place each of the candidates on the ethos scale, your vote is important enough to merit a deeper look. Ask yourself these three questions:

Does the speaker show good sense?

Does the speaker show good character?

Does the speaker show goodwill?

Good sense: The key here is not to use your level of agreement with the person’s logic as a measure of good sense; that would be logos. Good sense in a political candidate is shown by how they think, not what they think. For example, there are some candidates whose positions I disagree with, but I respect their approach to the question. Politics is the art of the possible, so they have to be pragmatic: will they be able to work with other people, will they be able to engage in outside-in thinking and take the perspective of the other side as well as their own? Do they think deeply about the issues, and are their assessments and descriptions of the issues anchored in concrete and facts and data, or are they only FOG: “Fact-deficient, obfuscating generalities”?

Good character: Character has long been one of the most important factors in American politics, but in this election cycle, we appear to be in uncharted waters with regard to its relevance. It was not that long ago that allegations of plagiarism during law school knocked a candidate out of the Presidential race; today, it seems that any skeleton can come safely out of the closet and be ignored. But I think it’s only because fear, anger and frustration—pathos—are currently overwhelming these questions, and they will eventually loosen their grip on voters’ judgment. These questions will reassert themselves: Does the person appear to be honest? Have they shown a tendency to do the right thing in the past? Do they share your values, and do they appear to live up to them?

Goodwill: Does the candidate appear to have the best interests of the audience at heart, or is he or she seen as lonely out for themselves? Do you get the sense they would do the right thing for you even if it is personally costly to them? Do they have your back, or just worship their own backside? Would they say or do anything just to get elected?

It’s important to note that ethos is not something the speaker “has”, so much as it’s a quality that the audience ascribes to him or her. In other words, ethos is in the eye of the beholder, which means that you are the ultimate judge. That’s why I did not directly answer the question that was asked of me in the class, nor do I here. My opinion does not matter, only yours does. To help you in your decision, here’s a template that you can use before you pull that lever: