For some reason, most of us draw a clear line between conversations and presentations. It’s like crossing the border from a comfortable and familiar territory into a dangerous land–I’ve known incredibly charismatic and articulate individuals who totally lose their personalities or morph into stuttering fools when the number of listeners leaves single-digit territory.

When these individuals learn how to approach presentations more as conversations, they tend to relax a bit more. They begin to talk with, not at, the audience, they dial back on the formality, and they engage the individual audiences on a more personal level. Both sides benefit from the change.

However, based on some recent coaching experiences I have had, I’ve come to realize that sometimes the equation should also work in reverse: some people might be helped by seeing their individual conversations more as presentations.

Why? When you cross into presentation territory, you know people are judging you, so your guard goes up and you increase your preparation, focus and situational awareness. A well-crafted presentation has a clear purpose and structure, the speaker is more careful in his word choice, and generally has a heightened awareness of his demeanor, delivery, and impact on the minds of the listener.

These characteristics raise your game and make for successful presentations, so why do speakers forego those advantages when they let their guard down in daily conversations? In letting their guard down, what they gain in relaxation they may pay for in terms of reduced conversational effectiveness. They may be unfocused or rambling, they get sloppy in how they express their thoughts, and pay less attention to how the listener is receiving their message.

Even a conversation between two peers who work closely with each other on a daily basis—certainly when a subordinate is speaking to a superior, there is some judging going on, even if neither party is conscious of it. At one of my clients, it’s commonly accepted that “you’re always interviewing for your next job.”

Just like TV news anchors occasionally get into trouble by saying something inappropriate because they think they’re off the air, you should treat every business conversation as if your mike is on. Even in a “normal” conversation, why wouldn’t you have a clear purpose and focus for the conversation, why wouldn’t you choose your words carefully, why wouldn’t you pay attention to your demeanor and delivery?

We’ve all been on the receiving end of long and convoluted explanations. We ask someone a simple question and get a dissertation in response. When it happens, we get impatient, interrupt, look for a graceful way out, while the oblivious talker merrily keeps right on going. We often leave those conversations feeling like we know less than we did when we began.

We’ve all been on the receiving end of long and convoluted explanations. We ask someone a simple question and get a dissertation in response. When it happens, we get impatient, interrupt, look for a graceful way out, while the oblivious talker merrily keeps right on going. We often leave those conversations feeling like we know less than we did when we began.

This situation is far too common when experts on a particular topic explain things to others. A lot of explanations proceed like a sailboat against the wind; they tack back and forth and take a long time to reach their destination; “on the one hand, on the other hand…”

It’s bad enough to have to listen to those who talk too much, but what if you are the one on the transmitting end of those explanations?

Why it’s a problem

Short memory and attention spans. Attention spans are shorter than ever, so it’s important to get your point in as quickly as possible. Since they won’t remember every detail you told them, don’t bury your main point in interesting but irrelevant detail. It’s especially important as you talk to higher-ranking executives.

It erodes your credibility. When you talk too much, you appear insecure and unsure of yourself and your position. Most people believe, like Einstein, that if you can’t explain something simply, you don’t understand it well enough. That may not always be true, but that is the impression they get when you over-explain. Concise explanations convey confidence.

Talking past the close. When you’re trying to sell others, they generally listen until they’ve heard enough to make a decision. If you keep talking after they’ve decided to accept your idea, you run the risk of giving them a reason to change their minds.

Loss of influence. Over time, people will stop coming to you for information if it takes them too long. They’ll stop asking for your input at meetings; they’ll turn and go the other way when they see you coming down the hall.

Possible causes

You’ve learned about the topic from the ground up, so you think that’s the best way to “teach” it.

You may be more concerned about seeming smart than about the needs of the questioner. Short, simple answers don’t show how much work it took to arrive at the conclusion.

You’re passionate about the topic, and you overestimate the interest that others take in it.

Because you know so much about the topic, small differences that are inconsequential to the questioner seem major to you.

You’re not prepared. When you hear a question for the first time, your answer is always going to be a rough draft. As any writer knows, the first version that comes out of your head can always be improved.

Solutions

Know your audience. If you know why they want to know, you can tailor your explanation to fit. It does not hurt to simply ask them why they want to know, or ask them a question or two to gauge their level of familiarity with the topic.

Prepare for conversations. This is related to knowing your audience, but also takes into account the specific topic and their relationship to it. Why do they care? What concerns or questions are they likely to have? What do they need to know to make the decision? If you’re giving a presentation, rehearsal helps you shave away unnecessary detail. For example, you’ve probably noticed that when you tell a story several times, it tends to get shorter.

Listen carefully. It’s hard to give just the right amount of information if you didn’t fully hear or understand the question. Give the other person your full focus. Even when speaking, you want to keep an eye on their reactions. It may not be as obvious as looking at their watch, but you can generally tell when you’re giving them more than they need.

Think briefly before opening your mouth. You’re not on a game show, where you have to answer as quickly as possible. Because you can think much faster than you can talk, even a very brief pause can help you compose your thoughts and formulate a shorter and better explanation.

Start with the headline. Make your explanations like a newspaper article. Give them the gist of the entire story in your opening statement, and then drill deeper as needed or asked. For example, if they ask you, “Will it work?” you don’t begin by saying, “Well that’s a complicated issue. There are a lot of factors that go into an accurate answer to that question, depending on the situation…”

Instead, you can say, “In most cases, the answer is yes (or no), although there are certain factors which might affect that.” By putting out qualifiers like in most cases, you signal to the other person that there are nuances they might want to explore further, but the choice is theirs.

Go for quality over quantity. As Churchill said, you should treat your facts like cigars: Choose only the strongest and the finest. One strong reason to do something is better than one strong reason plus three weaker reasons. You can keep the weaker reasons in reserve, and send them in only if needed.

Be as precise as necessary, but not more so. It’s better to be roughly right than precisely ignored.[1]

[1] Is there ever a time for long explanations? Of course: when the other person asks for it, or when they are about to make a decision based on dangerously incomplete information. The first one is easy, the second is a judgment call you need to make.

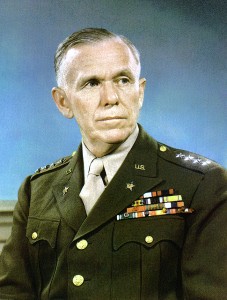

On May 13, 1940, as the Western front was reeling under Hitler’s blitzkrieg attack on France and the Low Countries, the United States had a small third-rate army, equipped with obsolete weapons. The new Army Chief of Staff, George Marshall, was trying to change that, but President Roosevelt wasn’t buying.

That morning, Marshall accompanied Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, according to the story as told by Thomas Ricks in The Generals: American Military Command from World War II to Today, to the White House to make the case for a major increase in spending to build up the military. Roosevelt made it clear that he did not want to talk to them, and after Morgenthau spoke in support of the measure, Roosevelt cut him off and said, “Well, you filed your protest.”

Morgenthau then asked the President to listen to Marshall, but FDR said, “I know exactly what he would say. There is no necessity for me to hear him at all.” Others in the room sat quietly, offering no support. As the meeting ended, Marshall approached Roosevelt’s desk and said, “Mr. President, may I have three minutes?”

The President assented, and then began to say something else, but Marshall, afraid that he might not get to speak, spoke right over him. He spoke rapidly, full of facts and figures, saying, “If you don’t do something…and do it right away, I don’t know what’s going to happen to this country. You have got to do something, and you’ve got to do it today.”

At this point, he had FDR’s full attention, and he went on: “We are in a situation now where it’s desperate. I am using the word very accurately, where it’s desperate.”

It must have been a powerful presentation, because the next day, Roosevelt asked Marshall for a list of what the military needed.

What can we learn from this extremely short but momentous speech? That sometimes it is possible to dramatically alter the listener’s attitude and position quickly if that’s the only chance you have. You too, can pull off this feat, as long as you have:

Command of the facts: It begins with content: your proposal has to be grounded in reality, and you must have the facts to back up your position. You must command your material so well that without overwhelming the listener with detail, you leave no doubt that you have all the details if needed. Besides being convincing, facts also provide a face-saving way for the listener to change his mind. When it’s about opinions, it’s hard to change someone’s mind because it can get personal.

Conviction: Conviction is not the same as passion, which is easily dismissed by the listener as purely emotional. Conviction comes from a solid foundation of thought, and the deep belief that your cause matters. It certainly contains a strong core of emotion, but that emotion may actually be more powerfully expressed by keeping it in check.

Courage: It takes tremendous guts to stand up to the President of the United States, but Marshall had the character and devotion to duty that in effect left him with little choice. But the collateral benefit of having the courage to state the truth to power, even when it can be personally very costly, is that it can confer tremendous credibility.

One final thought: Marshall already had a reputation in the Army for his ability to boil down complex issues to succinct statements. It was a skill he had honed over years, and it paid off for his country when it was needed most.

Have you ever heard someone (perhaps even yourself) say something like, “our best-in-class quality and performance provide superior value that leads to unparalleled increases in productivity for our customers”?

Try to picture each of these words in your mind. You can’t, because they aren’t real or tangible. There’s nothing “wrong” with words like quality, performance and productivity, but you’re not doing yourself a favor if your conversations don’t use words that listeners can see, hear, feel, taste, or smell.

What do you give up when you lose concreteness?

When you give a presentation, or just have a conversation to persuade someone, you want your listeners to: listen, understand, believe, imagine and remember. Here’s how being more concrete can help:

Listen: People can’t be convinced if they don’t pay attention. Business abstractions such as quality, synergy, world-class, are used so often that we automatically block them out as meaningless buzzwords, while concrete words have the power to grab the listener by the shirt and force them to listen. You can talk about quality, or you can give a dramatic demonstration of it, by showing how beautiful or how tough your product is.

Understand: It’s tough to convince people who don’t understand your ideas. When we first learn about something, we learn about real objects, and then we gradually climb the ladder of abstraction. When everyone in the room shares a high level of knowledge, abstraction is efficient and can convey credibility. But when you’re selling an idea to someone, they typically don’t know as much as you do about it, so there’s always a danger that you will be more abstract and vague than you need to be.

Believe: One of the best ways to earn credibility is to show that you have been there and done that. Those who have, talk about real events, real people, and real things, not airy abstractions. You can mention customer complaints, or you can name a specific customer and share the language they used. Being specific is another aspect of concreteness, which is why even numbers can be used to make something more real. You can say your solution speeds up their process, or you can tell them it makes it 17% faster, which translates to $3.4 million in additional revenue.

Imagine: You are much more likely to be killed by a deer bounding across a highway than by a shark, so why do you think about sharks when you swim in the ocean but don’t worry about deer when you drive? Maybe it’s because the mental picture of having your living flesh ripped from your bones as the water turns red around you is a bit more vivid than a collision with a moving object.

People act on your ideas because they want to move away from pain or toward gain, and they are more likely to move when they can actively imagine the pain or the gain. Imagining real pains gets the motor running, and envisioning the future can get the wheels moving in the right direction. King’s Dream speech is memorable and inspiring because he helped an entire nation picture a better future. On a more mundane level, research has shown[1] that concrete and specific implementation intentions are much more likely to be carried out than general desires.

Remember: Unless someone is making an immediate decision, which is unlikely in a complex sale, they’re going to have to remember what you said when they weigh the pros and cons. They will remember things and sensations more than they will remember concepts, especially when everyone is using the same concepts (quality, value, etc.) in their presentations.

How about a concrete example?

When Boeing designed the 727 in the 1960s, they could have told their engineers to design a best-in-class, high quality and high performance airplane. Instead, they told them to build a plane that could carry 131 passengers nonstop from Miami and land on runway 4-22 at La Guardia (because it’s a short runway).[2] Besides making it clear for the engineers, do you suppose it made it easier to sell to the airlines?