Last week, my church brought in a guest pastor from out of state who delivered a technically perfect sermon. Her message was strong and well-organized, she had great stories, her delivery was enthusiastic with excellent vocal variety and gestures that perfectly choreographed with her key points.

And I didn’t care for it at all. There was something missing. The message made sense intellectually, but I wasn’t touched at all on a personal level. She did not connect with me; she did not tap into a feeling that I could relate to.

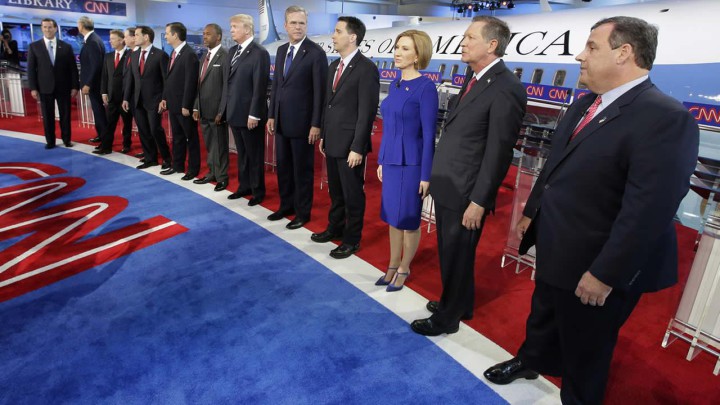

Similarly, I watched the presidential debates last night, and one candidate in particular piqued my professional admiration for his technique—but quite frankly he also gives me the creeps. That’s because I can’t tell whether he actually believes or feels what’s coming out of his mouth.

As I analyzed why I reacted this way to both of these examples, my first thought is that too much perfection is a bad thing. But as I reflected further, I don’t think it’s that. After all, Churchill, King and Reagan were also technically perfect, and they deeply touched millions.

I believe the pastor and the candidate missed the mark for two different reasons. The first can be cured with hard work, the second is probably terminal.

I think the pastor truly believed in her message, and genuinely cared about whether the audience benefited from it. Her intentions were pure, but she fell short in her technique. It wasn’t too perfect, it was just one step shy of perfection. Perfection is not only doing everything just right, but making it seem so effortless that it doesn’t call attention to itself. She gave off the impression that she was so proud of her skill that she wanted everyone else to notice it. The problem with that is that she succeeded: I was so busy watching the performance that I missed the message.

That can be cured by working on the technique even more, and getting it to the point where it’s truly unconscious and effortless competence. Here’s a practical example: most people don’t realize it, but natural gestures actually precede the words they support by a few milliseconds. When people are thinking about the gesture they want to use, it comes out at the same time as the words. The difference is so minuscule that we don’t consciously notice it, but something in our minds registers that it’s not right. So, how do trained actors get away with it? They “become” the person they’re portraying, and it becomes real. When you’re so good that it’s a part of who you are, the real you can come through, and that’s where connection begins.

The second reason is less about technique and more about character, which is why it might be terminal. Besides working on their craft over decades, the great speakers had something else that all the practice in the world won’t give you: they started from a place of genuine conviction and feeling and then honed their craft to improve their delivery. They did not work on delivery for its own sake. One got the sense that they cared how their message affected the listener, not how their delivery made them look. Reagan actually alluded to this when he said, “In all of that time I won a nickname, ‘The Great Communicator.’ But I never thought it was my style or the words I used that made a difference: It was the content. I wasn’t a great communicator, but I communicated great things…”

I am not against working on your style and delivery—after all, I make a living by helping people improve on those things. But I am against working only on style and delivery; I am against thinking that outer perfection can make up for inner conviction. If you don’t truly believe in your message, if you don’t truly believe that the product you are selling will help your listener, there is no amount of technical perfection that will help you in the long run.

In its purest form, lean communication is about making every word count, so in that sense repetition is just a form of waste. In fact, unnecessary repetition can even subtract value. For example, the old third T: “Tell them what you told them” can sound condescending to an intelligent audience. Or if they already got your point, they’re going to get restless and tune out if you belabor it by adding yet another example.

So in its purest form, the lean communication hero would be like the guy who, when his wife complained that he never said “I love you”, replied: “I told you I loved you when I married you. If anything changes, I’ll let you know.”

If you’ve already said something once, isn’t it a form of waste to repeat it? It may seem that way, but that’s like thinking that only the last blow of the sledgehammer cracks the concrete. If you remember that the most important requirement of lean communication is to add value, you can see why repetition can sometimes be essential. Value doesn’t happen just because it’s uttered; it has to be heard, understood, agreed and remembered. Any one of those things may not happen the first time you say something: they may have not paid complete attention, they may not have fully bought into your logic, they may be thinking of the consequences of what you said, and so on. So, if you said it and it did not have its full effect, what you said only once is waste unless you repeat it as often as it takes.

When done right, repetition is the ally of persuasion because of the mere exposure effect, which says that we tend to develop a preference for things just because they’re more familiar. Familiarity seems less risky, which is important because new ideas represent change, which can be scary at first but seem less scary as we grow accustomed to it.

Churchill said it best:

“If you have an important point to make, don’t try to be subtle or clever. Use a pile driver. Hit the point once. Then come back and hit it again. Then hit it a third time – a tremendous whack.”

Going beyond day-to-day business communication, repetition is one of the most fundamental instruments of inspirational and memorable oratory. In 1940, Churchill could have said, “We shall fight everywhere we need to.” Instead, he said:

We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills.

Martin Luther King could have said: “I have a dream, and in it I see the following (bullet points)”

Instead he said “I have a dream…” eight times. Was that wasteful? He said “Let freedom ring” eight times. Was that wasteful? He said “Free at last!” three times. Was that wasteful?

So repetition has its place even in lean communication, and it’s probably more important than ever because your listeners are so easily distracted. But if you decide to use it, you need to be smart about it so you don’t irritate your audience. Keep the following two rules in mind: First, pay close attention to the reactions of your audience and offer to go over parts that seem to be missing the mark. Second, when you do repeat your point, try to say it in a slightly different way.

Did you get all that? If not, go back and read it again.

The Presidential primary races this election season have been interesting, entertaining, and hugely confounding, as persuasion experts like myself have been proven wrong time after time. I thought for sure that Donald Trump would be undone by his extremist and outlandish statements, but instead he has continued to rise in their polls and show remarkable staying power. And it’s not just Trump: his brand of rhetoric seems to have infected others who feel they have to ratchet up their remarks either in response or just to be noticed.

My hope in writing this post is that I can prevent the spread of that infection to your persuasive efforts, by explaining that what works for them will not work for you.

First, let’s look at what’s working for the candidates:

Appeal to fear and loss: We know from Kahneman’s Prospect Theory that fear appeals work, because people are more likely to take risks to avoid costs or pain than to move towards gain. That’s why there’s so much talk of what’s broken in America, how we’re under unprecedented threat that threaten our existence, and how we are losing our greatness.

Extreme opinions and expression: Political correctness has done a lot of good things for the tone and content of our discourse over the past 50 or so years, but it has also gone too far and created a climate where people can be so easily offended—or at least pretend to be, to further their own goals. So, there is an understandable pleasure that people get when they hear others say publicly what they might be thinking but would not dare say.

Ad hominem attacks: Reagan’s 11th Commandment, “Thou shalt not speak ill of fellow Republicans”, seems a quaint relic of more genteel days. Debates have turned into cage matches, with politicians attacking each other’s personality, motives, backgrounds, and even their looks. While this can actually liven up the race, it unfortunately crowds out criticism of their actual positions and prevents substantive discussion. Why take the time to patiently explain your position when it’s easier and faster to trash the competition?

Whether this brand of persuasion will continue to be effective in the coming weeks when voters actually go to the polls and make a choice is still an open question, but I’m not going to bet against it. It seems to be working really well, so why wouldn’t it work for you, in your sales or internal persuasive efforts? There are at least three good reasons:

First, others expect different things from you. In business there is still a strong expectation of professionalism and civil behavior, and violations are usually swiftly punished. Speak ill of the competition and you may not be invited back; overstate the fear appeal and you risk a backlash.

Second, you usually have to live and work closely with the people you’re trying to persuade, and scorched earth tactics that may work once will carry long term consequences. Trump can get away with saying shocking things because it’s part of his ethos; it’s what people expect from him. It’s highly unlikely that you could pull it off, and the unemployment lines are full of people whose career was undone by one careless remark. While a guy like Trump can’t lose from his tactics (he either wins the election or goes back to TV as an even bigger draw), you can.

Third and most important is the fact that the people you are trying to persuade in business are on average better educated, more intelligent, and usually have a strong stake in the decision you’re trying to influence. They are turned off by strong one-sided appeals and respond more favorably to two-sided appeals, in which you at least make an effort to understand the other side.

All this doesn’t mean that you can’t use some version—albeit much more moderate and toned down—of a couple of the candidates’ effective tactics. Here are a few suggestions.

Appeal to fear and loss: Don’t dump this as a useful persuasion tool. For example, SPIN selling approaches are powerful precisely because they bring in the Implication of inaction. But for that to work, the Implication has to be something the other person legitimately accepts, and that’s why questions rather than direct statements are the best way to bring them out.

Extreme opinions: That does not mean you should not have strong opinions or be candid when the situation calls for it. When something needs to be said, you should say it, but don’t confuse candor and directness. Candor is about having a responsibility to speak up when necessary, but directness is a choice about how to say it, and you can sometimes be more persuasive by mitigating your speech enough to make it palatable to your listener.

Ad hominem attacks: This is one tactic that I recommend you leave out of your repertoire entirely. Never do this, even when it’s being used against you. This includes trashing the competition, if you are a salesperson.

In summary, the rulebook for political persuasion may have changed, but it is still firmly in place for business and most personal persuasion, so don’t try to become a better persuader by closely following politics—spend that time reading this blog instead.

As I wrote last week, lean communication is an enormously useful tool for ensuring that your communication with others adds value, briefly and clearly. But human nature is too complex to be reduced to ironclad rules.

Think of this article as the disclaimer to that one. In persuasive communication, there are always exceptions. There are definitely times when you might want or need to violate some of the rules. Let’s go through each:

Added-value:

The rule here is to add value to the recipient, which means framing your message in a way that is good for the other person. There are times when this rule does not apply…

- If the situation demands instant compliance, brevity and clarity should trump added value.

- Some pies can’t be made bigger—you want a slice that will just make theirs smaller. When you want something from the other person and there is no clear benefit to them, trying too hard to make it seem like it’s in their best interests can expose your insincerity; it’s better to be up-front about the fact that’s it’s not win-win.

Brevity:

The rule is to eliminate unnecessary verbiage that does not add value to the communication. But you still have to be smart about it…

- Anyone who has a teenager knows the frustrations of dealing with excessive brevity. Keep the relationship in mind when deciding how brief to be. When EQ is more important than IQ, sometimes you have to take more time to make the other person feel heard or valued. It’s easy to cross the line from brisk to brusque, especially because it’s the other person who decides where that line is. You have to use your common sense and judgment and most of all pay attention to the other person.

- Never forget that brevity which derives from deep thought is a totally different concept than sound-bite brevity, which is a product of shallow thinking, closed-mindedness, and snap judgments.

Clarity:

In general, you want to transfer what’s in your head with as little chance for misunderstanding as possible, except in these cases…

- There are benefits to ambiguity, imprecision and wiggle room in communication. When the idea you’re proposing is likely to be opposed by the other person, it’s not a good idea to begin with the bottom line up front, because of the risk that they might immediately stop listening or listen only to poke holes in your argument. In such cases, the shortest distance between two persuasive points may be a loop that starts from where they are and gradually circles back to your point of view.

- If your listeners are already on your side but your logic is less than airtight, being too clear may expose your weaknesses. Am I advocating fudging? What do you think? You may find this distasteful, but it’s the foundation of marketing and advertising; let your conscience be your guide.

- When clarity crosses the line to being “brutally honest”, it has definitely gone too far.

- When it’s not worth your time: My friend Gary told me a story about being at a conference with a colleague who had an inflated opinion of his own speaking ability. After he spoke, he asked Gary what he thought of his presentation. Gary replied, “Of all the presentations I’ve seen today, yours was definitely the most recent.” The fellow beamed and strutted away.

In another context, George Orwell wrote six rules for writers that align with brevity and clarity, but probably the most important is his last: “Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.” In that spirit, strive to add value, briefly and clearly—except when it contradicts your more important goals, common sense, or good taste.