One of the easiest mistakes for a presenter to make is to use language that your audience does not understand. Two of the most common ways to do this are using specialized jargon and using sports analogies. However, there is another problem which was brought home to me during today’s presentations class: the use of terms that only your generation understands.

I was telling the group that a good way to keep their presentations concise is to front-load their message by giving the headline and then the key points first, and then adding additional detail as necessary—just as a newspaper article is written. One of the participants said, “What’s a newspaper?” Of course, she said it tongue-in-cheek, but then she added seriously that many of her peers do not read newspapers, and haven’t for a long time. So, my analogy did not have the effect I thought it would have.

Brevity is a communication virtue because it increases the chance of your message being heard and understood. The best way to be brief is to state your point up front and then add detail as necessary.

In this increasingly distracted world, people just won’t take the time to listen for very long to what you have to say, so it’s important to get your message across succinctly and efficiently. Make sure that if they tune out, they have at least heard the main point.

Think about a newspaper article. The headline tells you the main point, so that if you’re too busy to read the article, at least you have a general idea of what happened. Next, you read the first paragraph, which tells you the “who, what, where, when, how and why”. Journalists call this the inverted pyramid technique, in which the critical information is at the top of the pyramid and the least significant details at the bottom.[1]

Besides ensuring that your main point will be heard, brevity will make it easier to understand. The mental discipline that you go through to figure out your main point can only help to clarify your message. This is why busy leaders like Churchill and Reagan insisted that any issues presented to them had to be contained on one sheet of paper. Think about it: Should we invade France in 1943 or 1944? Negotiate with this fellow Gorbachev? One sheet of paper.

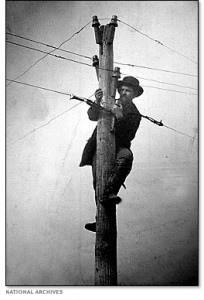

[1] In my classes, I’ve often told the story that the inverted pyramid was invented by America journalists during the Civil War who feared the lines could be cut at any time. Sadly, in researching this article I have just discovered it’s a myth. I say sadly, because it’s a good story and it allows me to compare your listener’s attention to telegraph wires that can be cut at any time.

A common theme among most presentation books and blogs is the importance of having and displaying passion for your topic. We’re told that passion excites and engages audiences and furnishes you with the fire to be strong and credible. And they’re mostly right: when you’re trying to instill a vision, motivate your listeners or inspire them to act on their beliefs, your passion may be the crucial ingredient that makes the difference.

But everything good comes with a cost, and too much passion can damage your credibility and effectiveness, especially for certain types of business presentations, for example when you’re trying to get a proposal approved internally, or selling a complex business solution to a key customer.

I generally try to post new articles on Tuesdays and Thursdays, but as of last night I had no clue what I was going to write about today. That quandary was resolved when I woke up about 5:30 after a series of very vivid dreams with a clear idea for today’s topic, in fact for a series of topics. My dream actually involved sharks, and my reluctance to dive into murky water to retrieve something I had lost because I suspected they were waiting to snack on my bony body.

I think the reason I woke up convinced that it was time to write about pathos is that the dream reminded me how reluctant we sometimes can be to dive beneath the surface of logic and explore the sometimes dangerous passions, feelings and sentiments that lurk below.