Are sales presentations dead? In this age of Sales 2.0, it’s easy to get that impression. We’re told that buyers are better informed than ever, that they have already gone through more than half the buying process when they first engage us, and that no one likes to be “sold”.

If this is true, then it would seem there would no longer be any need for a sales professional to know how to deliver a compelling presentation. Maybe it’s a far better use of their time to master social media instead.

On the other hand, that news would be extremely surprising to many top sales professionals who have made their year—maybe even affected the trajectory of their careers—by succeeding in those all-important strategic presentations. What does strategic mean? Quite simply, it’s improving your position (or clinching the deal) by saying the right things to the right people at the right time in the sales process. As an example, a top executive from a major technology firm told me that when a sales team from a major PR firm presented to their top management, within two seconds of their leaving the room, the president said: “Hire them.”

Sales presentations are still crucial to success in the complex sales for several reasons.

- It’s true that your buyers are getting a lot of information from the internet and other sources, and we all know that the information we get on the internet is 100% reliable, right? Whether your buyers are misinformed, or have missed some important insights, often the only way to correct the discrepancy is to gain the attention of the right people early enough in the sales process to be a part of their decision-making conversations.

- Most complex sales don’t end with a single transaction. The sales team must remain closely involved with implementation and ongoing support to ensure that the customer achieves the best possible outcomes from their purchase decision. The sales presentation may be the only way for all the people involved in the decision to get to know and gain a level of comfort with the sales team. You may represent a company that has billions of dollars in assets, but to them you are the company.

- If done right, the strategic presentation is definitely not a one-way transmission of information. It’s a superb way to have an interactive dialogue with all the relevant stakeholders and share insights that lead to better solutions.

- According to research cited in The Art of Woo: Using Strategic Persuasion to Sell Your Ideas, important corporate decisions involve an average of eight people in the decision. Major purchasing decisions will require at least that many, so at some point someone will have to present to all of them together. Why shouldn’t it be you?

- Other research by the HR Chally Group found that salesperson effectiveness accounted for 39% of the buying decisions of 300,000 customers surveyed[1]. A presentation to a high level audience is the most direct and dramatic way of demonstrating your effectiveness.

- Another interesting insight from my interviews with senior-level decision makers is that while they are often not experts in the technologies they are asked to decide upon, they do pride themselves on their ability to read people. They welcome the presentation because it gives them an opportunity to “scratch the surface” in a presentation and gauge the competence of the person presenting to them.

Willie Sutton was a famous bank robber in the 1950s. When he was caught, supposedly a reporter asked him why he robbed banks. Willie replied: “That’s where the money is.” The same still applies to strategic sales presentations today, no matter what some pundits will tell you.

I bet you never thought you would learn about one-celled organisms in a blog about persuasion, but bear with me for a few paragraphs because I want to make an important point.

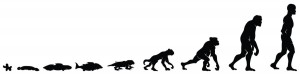

It’s been quite the fashion over the past few years in sales and persuasion circles to focus on our three brains: the reptilian brain, the rat brain, and the human brain. The idea is pretty simple: our human brains have evolved over eons in a different environment than our modern world; since evolution by definition proceeds from what went before, as our newer brain structures and functions evolved, the old structures remain and continue to be quite active. It’s kind of like the separation of powers in the Federal government: all three branches get involved in the process. So, if you want to persuade someone, you have to appeal to the simpler brains as well as to our logical faculties.

That may be true, but why stop at the reptile brain? If we trace our ancestry even further, we all evolved from one-celled organisms—amoebas, if you will, and we were amoebas even longer than we were reptiles. So, should we also tailor our persuasive efforts to the amoeba brain that surely lurks within all of us?

I can see it now: make sure you have a lot of light when you make your presentations, because amoebas move toward the light. You wouldn’t have to explain your solution, because people can get it by osmosis. We could call it “celling”. I realize I’ve reached the point of absurdity, but unfortunately so have many of the “scientific” persuasion experts.

The basic idea is sound, as long as it’s not carried too far. Aristotle, the father of modern persuasion science, made it the core of his Rhetoric, acknowledging that persuasive appeals comprise three strands, ethos, pathos, and logos. More recently, research has categorized and measured myriad ways in which our decisions and behaviors deviate from the purely rational. Science has learned a lot about the brain in the past few decades, and technologies such as functional MRIs let them see real time into our brain activity as we make decisions, respond to stimuli, etc. A lot of that research has confirmed, refined, or changed our understanding of how our minds work.

But new scientific discoveries are inevitably seized upon immediately by modern-day snake oil salesmen to add some legitimacy to their half-baked ideas. The ink was barely dry on the first edition of Darwin’s Origin of Species when the Social Darwinists hijacked his theories to justify their own notions of how society should be organized. In the same spirit, a lot of experts have picked up on the colorful pictures showing various areas of the brain lighting up during controlled laboratory experiments to market their services to companies, promising that they can read consumers’ brains and know what makes them tick, even better than the consumers themselves can. (By the way, if you’ve ever been inside of one of those machines, you know just how “natural” that situation is.)

When a book applies the idea to B2B sales, telling us that, “In spite of our modern ability to analyze and rationalize complex scenarios and situations, the old brain will regularly override all aspects of this analysis and, quite simply, veto the new brain’s conclusions.”[1], then the idea has gone too far.

I have a lot of respect for the work of one of the deans of persuasion science, Robert Cialdini, but even he goes a little too far. His six principles for influence are implied to be so powerful that you can’t sell a good idea without them, and you can definitely sell bad ideas with them. You can trigger fixed-action patterns that cause people to act like a mother turkey does when she hears “cheep-cheep”, and that’s what his book is about.[2] Cialdini at least acknowledges the importance of rationality—in a footnote—saying of course material self-interest is important, but that it goes without saying.

Yet, that’s the problem: it doesn’t go without saying. When a Harvard Business School professor tells us that “what you say is less important than how you say it”, and “style trumps content”, then it has to be said.

Content has to come first

This article is a plea for a little more, well, rationality in the understanding of what it takes to get ideas approved and products sold. Of course it’s important to be able to appeal to more than just the rational parts of the brains of your persuasive target. I’ve written about ways to do that many times on this blog. But it has to start with a sound, logical and defensible business or personal case—with what Cialdini called material self-interest.

One of the oldest sayings in sales is that you should sell the sizzle, not the steak. But what happens when they buy the appetizing sizzle and then find out the steak is crappy? They won’t come back. That’s why you have to make absolutely you have an excellent steak before you worry about the sizzle. Regardless of how many persuasive cues you employ, or which regions of the brain turn which color in the fmri, if the idea does not work, you soon won’t, either. Bad ideas are bad ideas, no matter how they’re dressed up.

One problem with fixation on techniques to appeal to the old brain is that they distract from the main job of putting together a strong proposal. There are people who spend most of their time learning “the tricks of the trade” in the hope of finding shortcuts, when they should be learning the trade itself. I’ve seen people put more time in the choice of fonts for their slides than they do in critically examining the strength of their ideas.

Whether you’re trying to get a proposal approved internally or selling a solution to a customer, most business decisions are complex enough to require extensive data, deep analysis, and careful decisions. That’s the reality of our modern world, which was built by the human brain. Never forget that it’s still the most important decision maker.

[1] Patrick Renvoise and Cristophe Morin, Neuromarketing, viii.

[2] Robert B. Cialdini, Influence: Science and Practice.

One of the more common ideas in motivation is what some people call the Bannister effect. For decades, once people began keeping records, it was thought to be impossible to run a mile in under four minutes, until Roger Bannister did it at on a windy spring day at Oxford on May 6, 1954. Two months later, he raced his great rival John Landy of Australia and won that race, with both men going under four minutes, and within three years 16 runners had gone under the barrier.

The moral of the story, of course, is that so often our limitations exist only in our minds, and when someone erases the mental limits, performance takes off. It’s also a testament to the power of belief, because Bannister’s belief is seen as the magic key that unlocked the sacred door.

It’s a great story and a powerful moral, except that, as in much of real life, reality is a bit more complicated.

When five o’clock rolled around after work one day last week, I was not motivated at all to do my evening workout. After a full day of proofreading and editing my new book, I was motivated to crack open a Heineken and relax.

Yet, despite my lack of motivation I still ended up doing a hard and productive workout, because even though I was not motivated, I was determined.

And that got me thinking, why do we always spend so much time focusing on motivation, when the real work gets done by determination? Why do so many of us listen to motivational speakers but don’t seek out those who tell us how to improve our determination?

I read a lot of biographies, and the thought struck me that when you read about the accomplishments of great men and women, the word motivation almost never appears. So I put it to the test, using the trusty Google Ngram viewer, which tracks the frequency of words in English language books, and this is what I found:

The word determination traces back to 1374, but in the meaning I’m using it here, as the quality of being resolute, it dates to 1822. Looking a little further, I traced the word motivation to 1873, and its use in the psychological literature to 1904, meaning “inner or social stimulus to action.”

And that’s the key word, stimulus. A stimulus will get you moving, but when things get tough you need a lot more than stimulus. Motivation gets you to the starting line, but determination gets you to the finish line.

Motivation is a state, determination is a trait. Motivation is about preferences, which can change at any time; determination is about character, which is a part of who you are.

Maybe that’s why the word determination started losing favor around 1960. Using the word implies a value judgment, and the sixties roughly coincided with the rise of political correctness in which words like character became embarrassing and judgmental. I don’t know for sure, but I’ll bet 1960 is roughly about the time that kids’ sports leagues started giving out prizes to everyone—not just the winners. They did that to keep kids motivated, which is an admirable goal.

But if no one ever loses, how do they develop the character that keeps them going when things get tough? How do they learn to hate losing and quitting so much that they stubbornly refuse to let it happen?

We need determination because we’re all pretty bad at predicting how we’re going to feel about a situation before we’re in it. For example, smokers underestimate the cravings they will feel when they’re trying to quit. We know we will be tired in the last lap of the race, but the reality feels worse than we imagined. Determination keeps us on course even when reality is worse than anticipated, and it often is.

So much of achievement depends on the patient and consistent application of the right process and method to achieve a long term goal. The goal motivates, but sometimes when the pain, fatigue and boredom speak louder than the eventual payoff, it’s easy to cut corners. That’s when you need determination—the unwillingness to quit and the firm resolution to keep going. Determination in some ways is a negative word: not quitting is more important than keeping going.

Motivation without determination is fragile and fleeting—compare the attendance at any gym in America in early January and early February to see how far motivation alone will take you. Motivation prompted Roger Bannister to dare the four minute mile; determination kept him doing the laps and the intervals even while pursuing his medical degree full-time.

Motivation with determination scales mountains, breaks the four-minute mile, paints the Sistine Chapel.

- Motivation contemplates the future; determination focuses on the here and now.

- Motivation is fragile and flighty; determination is strong and steady.

- Motivation is Red Bull; determination is red meat.

- To paraphrase Mike Tyson, “Everyone is motivated until they get punched in the face.”

- Motivation soars in the clouds; determination slogs grimly through the mud.

Determination is not a guarantee: on Everest, Mallory and Hillary both had it. But it’s that lack of guarantee which makes it so much more meaningful and so much more noble.

By the way, that Heineken I wanted? It made for a great recovery drink after my workout.