What’s the major cause of talking too long and losing your audience?

It’s something I’ve observed for too many presentations, and even one-on-one conversations. In fact, it’s the principal reason that many of my clients hire me to train their staff to become better communicators, because it’s one of their biggest sources of personal frustration—especially when they suffer through seemingly endless technical presentations.

I’m sure by now you’re wondering what it is, and I’m in danger of losing you, because I’m actually doing it to you right now.

Instead of getting right to the point, I’m taking the “long and winding road” or “tell them how to build a watch” approach, and I’m sure you’re familiar with it. In fact, by now you’re probably asking yourself, “Are we there yet?”

I call it BLAB, or Bottom Line At Bottom. As you can see, it’s frustrating, time-consuming, and even confusing.

What’s the antidote to BLAB? Simply put your bottom line at the top—start with BLUF: Bottom Line Up Front.

What if, instead, I had begun by saying: “The major cause of talking too long and losing your audience is putting your bottom line at the bottom”?

That would have helped you because you would have understood my main point unequivocally up front while you were paying full attention. At that point, you may have told me you agreed and I could have stopped. Or you may have wanted to hear my reasoning, and I could have given it to you, but at least you would have had the advantage of knowing the destination of the journey we’re going on together.

If you’re in love with BLAB, take heart: there’s still a use for it. Go ahead and use it as a summary and a call to action, if you’d like—but only as a bookend to BLUF.

But the bottom line is: move this line to the top.

Your time is more valuable than mine, so I’ll get right to the point: I recommend that you read Writing Without Bullshit, by Josh Bernoff.

Because so much of your business communication consists of words on screen or paper, you have to be able to write lean if you want to be a complete lean communicator. That’s because even though lean thinking applies equally to spoken or written communication, writing poses its own challenges that require specialized approaches.

How is writing different?

The principal difference between writing and speaking is that written communication is asynchronous, which is a fancy way of saying that production and delivery of the message don’t happen at the same time. That can help or hurt your communication.

It can help because usually the first time you say something, you don’t say it as well as you could. Writing is like a ballistic missile: you can choose your target and take pains to aim properly. You can take time to think carefully about what you want to say and choose your words, and you can edit and polish as much as you want. On the receiving end, the reader can absorb your message at their own pace, re-reading if they have trouble understanding or skimming over parts that they already know.

It can hurt because if you’re off target, you don’t have the feedback loop of real-time dialogue which allows you to adjust, clarify and take in the listener’s viewpoint to improve your original message. Plus, if you write the way you were taught in school, you’re almost guaranteed to produce crappy writing. That’s because the sole purpose of writing in school is to make yourself look smart, not to help the reader improve their outcomes.

That presents a great opportunity for a good writer. Since most business writing is bland, boring or baffling, you can easily stand out and make a reputation for yourself by just being a little better than everyone else. Unfortunately most people throw away the advantages of writing by not taking the time to carefully craft and edit their message, so the bulk of business writing is full of waste, or to use the more colorful term: bullshit.

So what?

Fortunately, Writing Without Bullshit supplies the antidote. If I were to write a book on Lean Communication as applied to writing (and if I were a better writer), this is the book I would have tried to write.

So much of what Bernoff writes aligns closely with LC principles. That’s no coincidence, because a lot of my LC ideas have come from studying and trying to apply ideas from books on writing. Lean keys such as outside-in thinking, Bottom Line Up Front, and Transparent Structure all apply as well to writing as they do to speaking. But this book brings a writer’s perspective to the principles.

Let’s just focus on one his Iron Imperative, which you see reflected in the picture above this post:

Treat the reader’s time as more valuable than your own.

That’s Outside-In Thinking, applied to writing. It’s powerful because it focuses your mind on adding value to the reader without wasting their time. If you stick a post-it note with it on the top of your computer screen, it will remind you to take the time and make the effort so that your reader won’t have to, and it will hugely improve your writing[1].

Actually, that’s not exactly true. You will throw away the advantage you have as a writer if you don’t take the time and make the effort to carefully craft your message and choose your words. That’s why the second half of the book is so valuable. It’s about the project management aspect of writing, and it will teach you how to be productively paranoid, find your flow, and edit your own and others’ work effectively.

The nice thing about becoming a better writer is that it will make you a better speaker as well. So if you truly want to add value with less waste no matter what medium you use, you must learn to get rid of the bullshit. You—and the rest of the world—will be better off.

[1] I would be guilty of peddling bullshit myself if I didn’t disclose some disagreements I have with Bernoff. While I agree with his Iron Imperative, I don’t believe it says enough about understanding the reader’s perspective and their needs. If the purpose of business writing is to change the reader, as he says, then one should think more deeply about the WIFM when writing.

Would your prospects and customers pay to talk to you?

The only way that’s likely to happen is if they know you will bring them useful ideas to improve their business outcomes without wasting their time!

One of the recurring memes in the B2B sales world is the idea that salespeople are an endangered species, because buyers have so many alternative sources that they can tap to get the information they need to make an effective purchase decision. And with all the other demands on their time, it’s no wonder that buyers put off talking to salespeople for as long as they can.

When quantity is unlimited, quality counts more than ever. Precisely because there is so much information available and so many voices clamoring for the attention of your dream buyer, they will welcome a trusted voice who will give them just what they need when they need it without wasting their precious time.

My new e-book, Lean Communication for Sales, will help you to become that trusted voice, by showing how to communicate more value in fewer words—and become a valuable asset to your customers. As a B2B sales professional, your role is to deliver the information buyers need to make the best possible decision.

Lean Communication for Sales will help you communicate higher value with less waste by applying the principles of lean thinking to your sales communication process. You will be able to apply 9 powerful ideas as simply as ABCD:

- Add value: Leave your customers better off by Answering the Question that is on every buyer’s mind, and using Outside-in Thinking to communicate what they value the most.

- Brevity: Save time and boost credibility by putting your Bottom Line Up Front, and use the So What filter to eliminate clutter.

- Clarity: Ensure that your message is heard, understood, and remembered through Transparent Structure, Candor, and User-friendly Language.

- Dialogue: Co-create value with your buyer through effective dialogue, using Just-in-time Communication and Lean Listening.

Talk less, sell more: improve the quality of your customer conversations with Lean Communication for Sales!

The best way to add value and reduce waste in communication is to provide your audience with “simplicity on the other side of complexity”.

I first came across this phrase in a fascinating blog post titled: Simplicity on the other Side of Complexity, by John Kolko, and he in turn took it from Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes who said, “I would not give a fig for the simplicity on this side of complexity, but I would give my life for the simplicity on the other side of complexity.”

The phrase resonated with me because it explains so clearly an idea that I am constantly trying to impart to participants in my lean communication and presentations classes. One of the most common reasons that companies bring me in to work with their teams is that their executives complain that they have to sit through unnecessarily complex and excessively detailed presentations, where masses of data substitute for clear understanding. The common complaint is “I ask what time it is, and they tell me how to build a watch.”

When you have to make a presentation to busy high-level decision makers—whether internally or to a potential customer—it’s because they need information to grasp the key issues about a complex decision, so that they can take effective action to improve outcomes. The simplicity with which you express information clearly adds value to them, because it reduces uncertainty and saves time and effort. But only if it’s good simplicity, which resides on the other side of complexity.

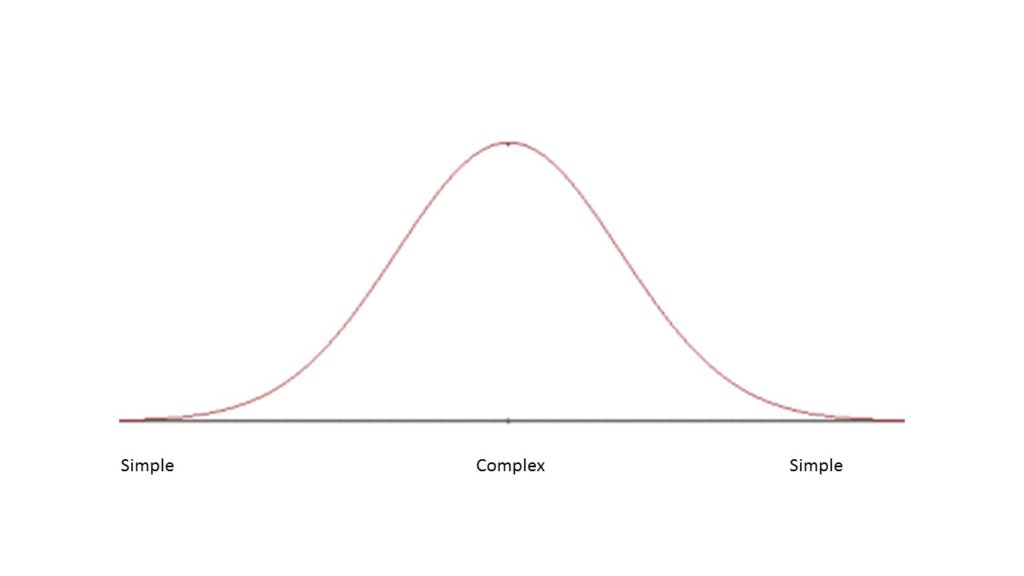

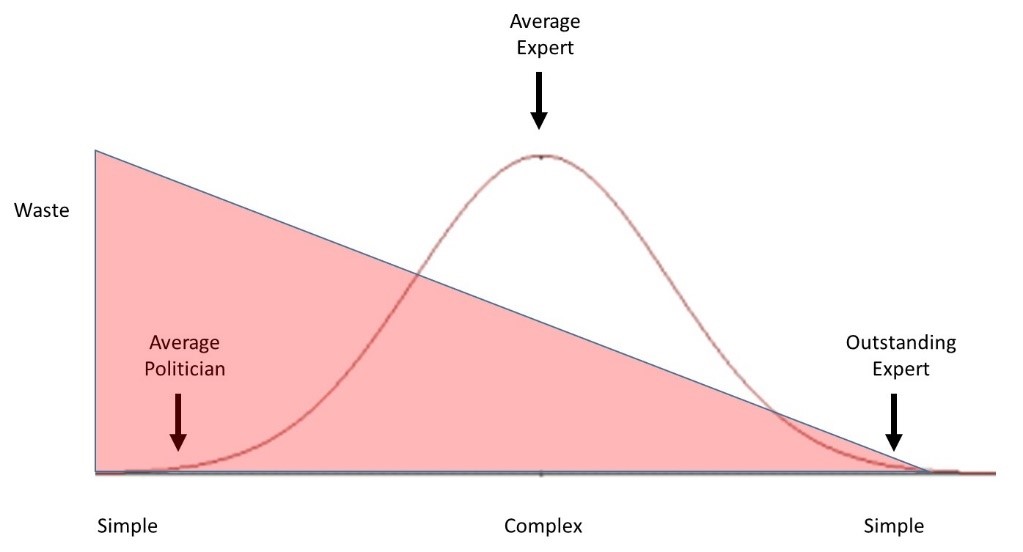

In essence, the gist of Kolko’s article is that the learning curve for a complex issue looks like a bell curve (I’ve added the labels to his simple drawing, and the rest of this article includes my additions to his):

At the far left, when people first approach an issue, they know very little about it, but of course that doesn’t stop most of them from jumping to conclusions or forming opinions. People who are intellectually lazy or who use motivated reasoning don’t proceed past this stage and enjoy the confidence born of ignorance. They forget what H.L. Mencken said: “Explanations exist; they have existed for all time; there is always a well-known solution to every human problem — neat, plausible, and wrong.” For examples of this type of presentation, just think back to the past two weeks of US Presidential conventions. This kind of simple is almost pure waste, because it’s either wrong, or it’s trivial.

But you’re a business professional, so you can’t afford to be intellectually lazy because you know if you present a simplistic and shallow case you will be eviscerated in the boardroom. So you take your time, gather evidence and analyze it, and see greater depth and nuance in the issues. If you stick to it, you eventually become an expert; you “get it”, so that’s the next natural stopping point. Complexity is the point at which the average expert feels they are ready to present their findings. However, the biggest mistake they make is that they include far more detail than the listener needs to use their findings, either through defensiveness or inability to connect to what the listener cares about. As one CEO told me, “I get a lot of detail but very little meaning.” They may have added value, but there is still a significant amount of waste, in the form of time, effort, and confusion.

Outstanding expert presenters know that you never truly know how well you know something until you try to explain it to others, so they take the next logical step. They add value to their listeners by distilling all their hard-won complexity into just the meaning the listener needs for their purposes. They know exactly why the listener needs the information, and give them just what they need to know to make the best possible decision, so that there is zero waste. Most times, they go beyond merely providing information and advocate for a specific decision (which is a given if it’s a sales presentation)—but it’s based on highly informed judgment.

The tools for achieving this type of good simplicity are the tools of lean communication: Outside-in thinking to know what the listener needs, Bottom Line Up Front to provide meaning right away, SO WHAT filter to root out waste, and pull to make adjustments as necessary.

Before you decide to strive for good simplicity, I would be remiss in not pointing out one personal risk you might run: if your goal is to call attention to how smart you are, it may not be the best way. As Kolko says, “The place you land on the right—the simplicity on the other side of complexity—is often super obvious in retrospect. That’s sort of the point: it’s made obvious to others because you did the heavy lifting of getting through the mess.”

But if your goal is to get the right things done, simplicity on the other side of complexity is the only way.