In my series on Lean Communication, I have so far focused on the transmission side of the communication: how to increase value and decrease waste in what you say or write.

But there is probably no aspect of communication which contains more waste than listening. We’re all guilty of divided attention, selective hearing, and overconfidence in our ability to understand. The result is error, inefficiency, wasted time, and damaged relationships.

Lean listening is such an involved topic that I will cover it in four separate articles. In this first one, we’ll examine the major cause of waste in listening, which by coincidence is also the best tool we have for ensuring maximum value with minimum waste. In other words, the obstacle is the way to lean listening.

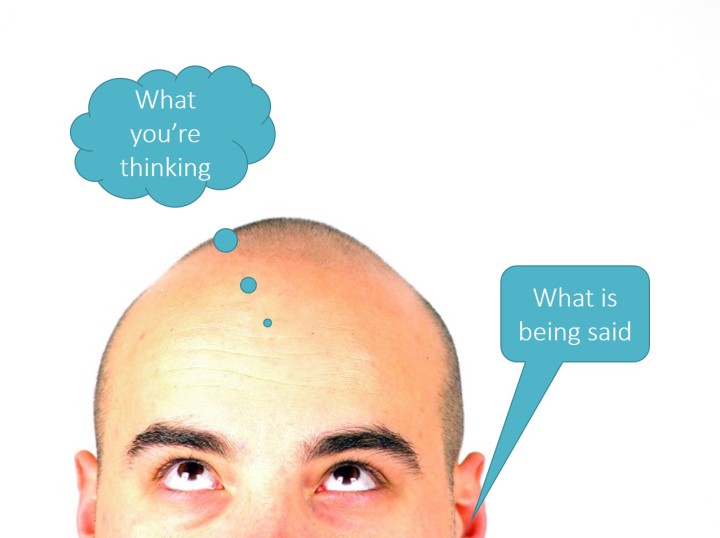

The major reason for waste in listening is the second conversation that goes on in our heads while listening, which is caused by the bandwidth mismatch between speaking and thinking. Standard American English speakers produce about 125 words per minute, but we process words mentally at least four times as fast (and flashes of insight and intuition may be orders of magnitude faster). While that should make it easier to follow what the other person is saying, what happens instead is that the extra processing capacity usually goes to the second conversation that we have with ourselves while someone is speaking.

It’s extremely difficult to avoid the second conversation during a dialogue. When the other person speaks, we listen to their words, and at the same time we listen to ourselves: our reactions, impressions, questions, or rebuttals that spring unbidden into our minds in response to their message. Or we use the extra bandwidth to think about something totally unrelated to the conversation, maybe because something else has caught our attention.

Sometimes that second conversation helps our understanding, but more often it interferes, because we truly can’t carry on both conversations at once. Even if it’s momentary, we stop listening to the other person long enough to hear ourselves—but sometimes we don’t revert to the first conversation in time, and miss something that was said. Or, we automatically assume we know how the sentence is going to end, and begin forming our response, and we miss the zig where we expected a zag.

So, what can we do about it? The trick is not to try to silence your second conversation—you can no more slow down your rate of thinking than you can control your heartbeat. The trick is to use the second conversation to support your listening rather than interfere with it. The second conversation become a help and not a hindrance when it gets you focus tightly on the value of what is being said, find or impose order on it, and cut through the clutter of waste in their conversation.

Think of the second conversation as a coach who is in the room while you are talking to the other person, who is closely paying attention and is asking questions to make sense of what’s being said and not said. But not just any random thought that comes to mind: this coach is listening for lean communication from the other party.

To make sense of that last statement, think about it this way: if the other person is communicating in a perfectly lean manner, you would not have to improve your listening, because you would get exactly the information you need for your purposes. But since that usually doesn’t happen, the main purpose of lean listening is to help the other person be lean. You do this by listening for the aspects of lean communication that contribute to value and waste, and ask questions or adjust where there are gaps.

The important thing about the second conversation is to keep it focused on asking questions only about what is being said (which includes non-verbals), not about what you are planning to say in response. The questions you ask yourself are the ones that keep you focused on finding the five major elements of lean communication, which is the topic for the next three posts: Lean Listening for Value, Lean Listening for Waste, and Lean Listening Techniques.

This is my 500th blog post, and I could think of no more fitting topic for such a milestone than this: the first rule of effective communication.

The first rule of effective communication is this: you must add value. I’ll describe what that means and share a checklist for measuring the amount of value you have added in any communication, whether it be a sales conversation, a presentation, or simply answering a question from your boss.

What does it mean to add value in communication? Remember that in lean thinking value is defined as anything the customer is willing to pay for. By analogy, value in communication is anything the recipient is willing to listen to, and use as a basis for a decision or action. What would make them be willing to listen and act? Because the information received is useful: it will improve their situation in some way.

Value is then defined as useful communication that respects the relationship. You know you have added value when one or more of the following things happen:

- Either or both sides are better equipped to make a decision or take action that improves their personal situation.

- The organization is better off or a higher purpose than individual gain is served.

- The relationship is preserved or enhanced.

In an ideal world, you would be able to meet those three conditions in every communication, but of course that’s not always reality. Which of the three you emphasize when there’s a conflict depends on you: on your judgment, your values, and your appraisal of the situation. But having said that, you can usually find ways to accomplish at least two of the three, and you should probably not open your mouth unless you can do so.

Here’s a checklist to ensure that your communication adds value to the other person. At the end of the exchange, here are some questions that will tell you whether you added value:

Did you answer the question? When someone else asks you a question, it’s usually easy for all concerned to tell whether you provided an answer. But the same test applies when you are the one initiating the conversation. There is always the question that requires an answer, although it’s not so obvious. That question is: “What do you want me to do and why?” If someone takes your call or attends your presentation, this question is always on their mind, or should be. You can hear people talk for hours and not be sure whether the question was answered.

Did you improve their situation or outcome? The second part of the question is “why?” The bottom line of communication is that the information received is useful: it enables the recipient to solve a problem, take advantage of an opportunity, or deal with a risk. To pass this test, you must tell the other person what he needs to know, not what he wants to know. Focus on WIFM: “What’s in it for me?” Did you provide a personal benefit to the listener? While this is not always possible, ultimately all decisions are personal, so you should strive to frame communications in terms of the other person’s benefit. The only exception is when they need to do it to benefit a higher purpose, such as what’s good for the business. If your ask does not benefit the other person or a higher purpose, your only alternatives are begging or coercion, depending on who holds the power.

Did you maintain or improve the relationship? This is not always possible—sometimes what the other person needs to hear is not what they want to hear. But you should always be respectful and sensitive to the relationship if possible.

Who did the work? Remember that you’re a knowledge worker, not an information worker. Many communications are a “data dump” in which the speaker tells everything they know, and the listener has to draw conclusions from all the detail. If you present all the information in your head without analysis or recommendation, you are asking the other person to do your work for you. Give them your best finished thought.

Did you listen and adjust? One problem with giving them the best of your finished thought is that you may fall in love with your own idea, and you may miss opportunities to create even more value. During the conversation (and I use this term very broadly, to include any type of ongoing discussion or communication), you can jointly create even more value through dialogue. Dialogue enables correction, adjustment and improvement to the original idea, and can often spark new and better ideas—not to mention greater engagement and commitment. Of course, this will only work if you are willing to be influenced yourself, and if you actively listen and pay attention to how your ideas are being heard, understood, and processed by the other person.

These five questions may seem like a lot to remember, but they can become automatic through awareness and practice. The bottom line, and the first rule of effective communication is this: Before you open your mouth, stick in a slide, or hit send, ask yourself: “What value am I adding?”

As I wrote last week, lean communication is an enormously useful tool for ensuring that your communication with others adds value, briefly and clearly. But human nature is too complex to be reduced to ironclad rules.

Think of this article as the disclaimer to that one. In persuasive communication, there are always exceptions. There are definitely times when you might want or need to violate some of the rules. Let’s go through each:

Added-value:

The rule here is to add value to the recipient, which means framing your message in a way that is good for the other person. There are times when this rule does not apply…

- If the situation demands instant compliance, brevity and clarity should trump added value.

- Some pies can’t be made bigger—you want a slice that will just make theirs smaller. When you want something from the other person and there is no clear benefit to them, trying too hard to make it seem like it’s in their best interests can expose your insincerity; it’s better to be up-front about the fact that’s it’s not win-win.

Brevity:

The rule is to eliminate unnecessary verbiage that does not add value to the communication. But you still have to be smart about it…

- Anyone who has a teenager knows the frustrations of dealing with excessive brevity. Keep the relationship in mind when deciding how brief to be. When EQ is more important than IQ, sometimes you have to take more time to make the other person feel heard or valued. It’s easy to cross the line from brisk to brusque, especially because it’s the other person who decides where that line is. You have to use your common sense and judgment and most of all pay attention to the other person.

- Never forget that brevity which derives from deep thought is a totally different concept than sound-bite brevity, which is a product of shallow thinking, closed-mindedness, and snap judgments.

Clarity:

In general, you want to transfer what’s in your head with as little chance for misunderstanding as possible, except in these cases…

- There are benefits to ambiguity, imprecision and wiggle room in communication. When the idea you’re proposing is likely to be opposed by the other person, it’s not a good idea to begin with the bottom line up front, because of the risk that they might immediately stop listening or listen only to poke holes in your argument. In such cases, the shortest distance between two persuasive points may be a loop that starts from where they are and gradually circles back to your point of view.

- If your listeners are already on your side but your logic is less than airtight, being too clear may expose your weaknesses. Am I advocating fudging? What do you think? You may find this distasteful, but it’s the foundation of marketing and advertising; let your conscience be your guide.

- When clarity crosses the line to being “brutally honest”, it has definitely gone too far.

- When it’s not worth your time: My friend Gary told me a story about being at a conference with a colleague who had an inflated opinion of his own speaking ability. After he spoke, he asked Gary what he thought of his presentation. Gary replied, “Of all the presentations I’ve seen today, yours was definitely the most recent.” The fellow beamed and strutted away.

In another context, George Orwell wrote six rules for writers that align with brevity and clarity, but probably the most important is his last: “Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.” In that spirit, strive to add value, briefly and clearly—except when it contradicts your more important goals, common sense, or good taste.

I’ve written before about applying lean manufacturing principles to business communication[1]. Although manufacturing and communication are two totally different activities, both share the goal of producing maximum value with minimum waste. In this post, I’ve tried to simplify it even further, and I’ve come up with the ABCs of lean communication.

I define lean communication as giving the other person the information they need to make a good decision, with a minimum of time and effort. Ideally, a conversation, presentation or a written communication will meet three tests:

- It must add value, leaving the recipient better off in some way.

- It must be brief, because attention spans are short and working memory is limited.

- It must be clear, so that they can glean useful ideas that they can put into practice immediately.

What does it mean to add value in communication? It’s communicating useful information that produces improved outcomes for both parties while preferably preserving the relationship. This implies three important ideas:

Lean defines value simply as anything the customer will pay for. By analogy, value in lean communication is defined as any information the listener finds useful, usually to take action or make a decision.

Second, while it’s certainly possible to communicate so that only one party improves their outcomes—such as a boss giving clear commands—it’s not sustainable in the long run. The word “both” recognizes that you have your own purposes for the communication, as you should, but you will be more effective and influential in the long run if you develop the habit of focusing on the needs, desires, and perspectives of the other person.

Third, I say “preferably” because sometimes the demands of the business or the situation will necessarily harm the relationship.

Adding value ensures that your communication is effective, but it’s also important that it be efficient, because everyone has limited time and mental resources. It has to be brief and clear.

Adding value begins with outside-in thinking, which the psychologists call perspective taking or cognitive empathy. The usefulness of your communication will be directly correlated to your understanding of the other person’s needs, wants, and existing knowledge. As Stephen Covey says, “Seek first to understand, and then be understood.”

Regardless how useful your message is, if your explanation is too long-winded it won’t add value because it won’t get heard. Being brief is your best chance at ensuring that your message will get through, because time is pressing and attention spans have withered away to almost nothing. But brevity is not just about efficiency—it also improves the quality of your message because it takes deep thinking to be able to distill your ideas into concentrated form. That’s why the paradox is that brevity takes time; you have to do the hard work so your listener does not have to. So, even though brevity is mostly about reducing waste, it’s actually another form of added value. Being brief also makes you sound much more confident and credible, which supports your purpose.

There are two approaches to cultivate the habit and discipline of brevity: BLUF and SO WHAT?

BLUF stand for “bottom line up front.” Give them the main point first, and then back it up with your logic and evidence as needed. It works for two reasons. For you, it forces you a clear conception of your own core message, which you often don’t know until you try to summarize it. For the listener, hearing the point you want them to accept helps them organize the incoming information, and it often creates its own brevity because they will stop you when they’ve hear enough.

In any communication, there is so much that could say, but only a small bit that you should say. Your mind is full of knowledge, some of which is integral to your key message, some important, and much that is interesting but irrelevant. SO WHAT? is your mental filter that ensures the first comes out, the second is available if necessary, and the last two stay in your brain.

While brevity focuses on shaving time from your message, clarity focuses on removing mental effort to understand it. Brevity and clarity can clash or cooperate. It’s possible to be too brief, because of the curse of knowledge. You don’t remember what it was like not to know what you know now, so you might leave out information that the other person needs to fully understand the situation. Besides leading to misunderstanding, the main cost to you is that when the other person does not understand your logic or your explanation, the default answer is likely to be NO, because they won’t make the mental effort to understand and they won’t admit it’s unclear to them.

But brevity and clarity can also cooperate, because stripping out unnecessary detail can make the structure of your thinking easy to follow. But just to make sure, it’s a good idea to surface your logic[2], which is making your logical argument explicit and providing signposts in your conversation. Tell them the structure of what you’re going to say, such as there are three reasons we need to do this. “The first is, the second reason is, etc.”

The second tool for clarity is the language you use. Speak plainly and directly, and don’t try to sound smart by using terms others won’t understand. It helps to make abstract concepts clearer by using concrete examples, but be careful you don’t insult the intelligence of your audience—which brings us full circle to the idea that knowing your audience is key.

Want to be known as a great communicator? It’s as simple as ABC: Add value, Briefly and Clearly.

Lean Communication: Delivering Maximum Value

Lean Communication: Reducing Waste

Lean Communication: Making Work Visible

[2] A wonderful phrase I learned from Bruce Gabrielle in his excellent book, Speaking PowerPoint.