Podcast: Play in new window | Download

So far in this series about the psychology of persuasion, we’ve talked about the first three things that happen in a persuasive communication effort. You’ve made a first impression, grabbed their attention, and delivered your message so that they could understand exactly what you intended. So, we have the communication part covered, but now we turn to the persuasive part. There are three aspects that I will cover in this and the next two podcasts. First, will they believe you? Second, can you influence their decision? Third, will the take action?

If you want people to believe you, content is definitely king, but it doesn’t rule by itself. Let’s suppose you’re presenting an investment proposal to a roomful of decision makers. It could be an internal presentation to your C-Level, or maybe a sales presentation. You put together a slide deck filled with charts, tables and hard data, and you present an airtight case. Will it be enough?

The answer is—it depends. Someone may question your sources, someone may agree on the facts but draw different conclusions from yours, someone might sense a little uncertainty in your voice and someone might not like the fact that your shoes aren’t shined. Of course, they won’t mention anything like the latter two reasons if they run you down, but things like that do make a difference.

There’s a lot going on in the listener’s mind as they’re judging your credibility. They’re consciously paying attention to your content while at the same time forming unconscious judgments about whether to trust you. And everybody is different. Some are like Spock and can set aside “feelings” while others won’t even try to follow your logical arguments—they just know they can trust their gut.

So obviously you would prefer to be as strong as possible in both the material and the source. I’m going to start with what types of material people find to be the most credible, and then look at the personal qualities that they perceive while judging whether to believe.

Content

We have to start here because content is king. And keep in mind that this podcast is about business communication, so we have to operate within the presumption that there is an objective standard that’s going to be applied. In this case, bottom line profit. Besides, your most important persuasive communication opportunities will be with high level audiences, so you generally have more sophisticated listeners who have a higher “need for cognition”.

Here’s a rough hierarchy of they types of evidence that people value:

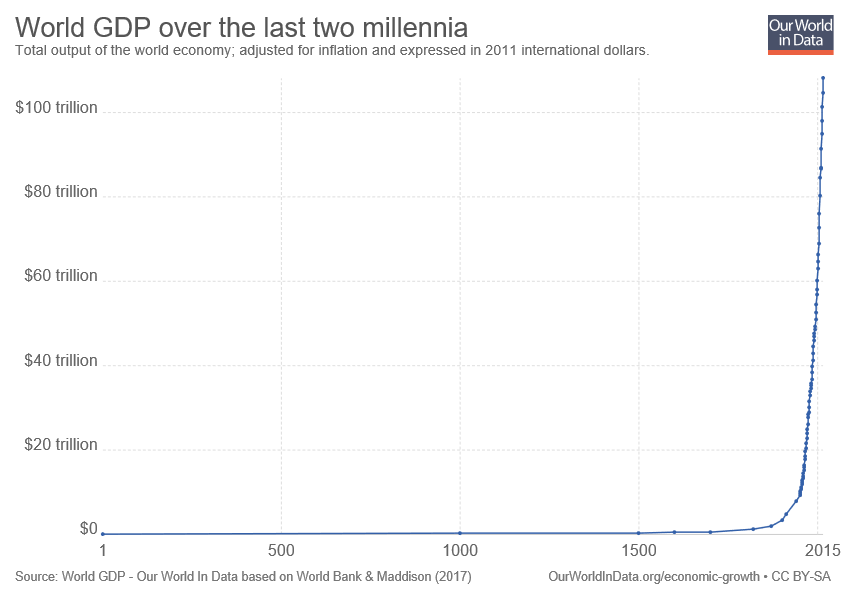

- Empirical data such as statistics and metrics – most business decisions are held to an objective standard.

- Personal observation – if you’re the only one who has been on the scene, they have to believe you.

- Appeal to authority- borrow credibility from someone with greater credentials or experience.

- Social proof – if other companies are doing it, we’d better not get left behind.

- See for yourself – make it concrete and visible.

- Causation and common sense – even if it hasn’t been done before, show that it’s plausible.

- Because I said so – Trust me, I’m an expert. (Only works when you already have credibility.)

Personal Credibility

Besides Content, there are four other C’s of personal credibility:

- Credentials – what are your qualifications and experience?

- Clarity – are you candid and direct, and do you have a command of the facts?

- Confidence – do you believe in your own proposal without being overconfident?

- Concern – do you care about what’s in it for me?