Podcast: Play in new window | Download

As part of my research into my book on Lean Communication, I have been interviewing CEOs to get their perspectives on the general quality of communication they receive from their subordinates, and I’ve received excellent ideas and suggestions to pass on to my principal intended readers. But almost invariably the leaders I’ve spoken to have reflected on what they need to do to improve their own communication, and that has caused me to think about adding a special chapter on lean communication just for leaders.

If you’ve risen to a high level of leadership within your organization, you’re probably already a good communicator, even if you haven’t been formally exposed to Lean Communication. That’s the good news.

But the bad news is that as you rise you need to raise your communication to an even higher level, while at the same time you’ve got two factors working against you to erode whatever skill you have developed.

You need to raise your communication for the simple reason that your position gives you greater reach and influence, which means that every word you utter or write carries more value or creates more waste. You speak to more people about more consequential topics than ever before, and they listen more carefully and rely more heavily on what you say. That places a heavier onus on you to get it right without getting in their way or wasting their time. The higher you go, the more critical it becomes to be a lean communicator.

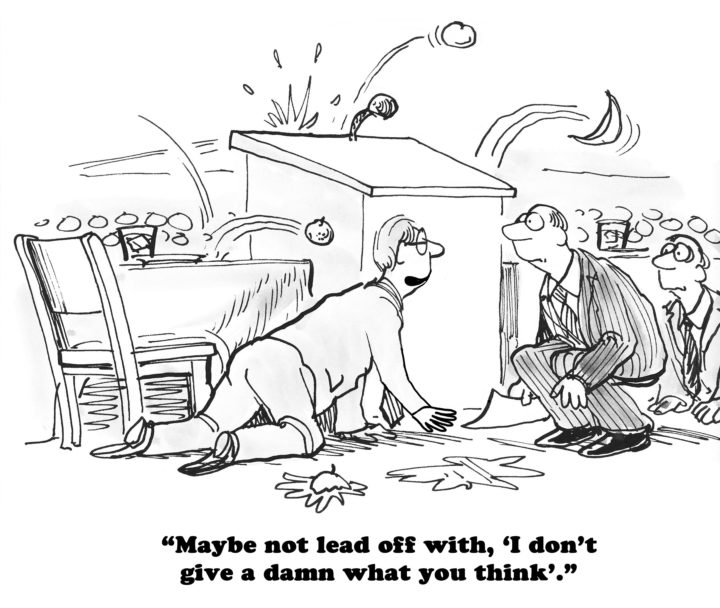

Unfortunately, just as it becomes more important to raise your game, you run into two natural human tendencies that can weaken your skill. To put it bluntly, you get lazy and you care less about what others think. Those are pretty tough words, so I’ll explain the first in this article and the second in the next.

What do I mean by “getting lazy”? Think about things that once came easy to you that you that you’d be hard-pressed to do well now: maybe remembering phone numbers; doing mental math; driving a stick shift; reading a map; baking a cake from scratch. As we find newer and easier ways of achieving our goals, of course it makes sense to stop using the old skills, and it doesn’t cause any harm—until we need them.

What does this have to do with leadership communication? Quite simply, the higher you go, communication seems to get easier, because people are more likely to listen carefully while you speak, laugh at your jokes, ask your advice, and do what you suggest.

Stanford Business School professor Jeffrey Pfeffer recently wrote:

“A colleague of mine who teaches at Duke University recently told me about a speech he attended on campus by the CEO of a company that is best left unnamed here. It turned out to be a terrible speech — riddled with platitudes, internal inconsistencies, and false facts. On his way out the door, my friend overheard two students discussing what they’d just heard.

“He’s incredibly rich,” one of them said. “He must be smart.”

That CEO gave a terrible speech, but paid no price for it. Do you think he’s going to work hard for his next one? Rich people, famous people, people with impressive titles: they all get a pass.

I personally see the trend with authors I admire. Their early work is excellent—it’s what gets them noticed and helps them become best-sellers. I buy the next book they write and maybe the next after that. Almost invariably, though, they seem to reach a stage when they mail it in, as if their name alone is enough to sell books. (When the author’s name on the book jacket is larger than the title, that’s a pretty good sign that they’ve reached that stage.)

Beware the Ethos Trap

I call it the ethos trap. As Aristotle taught us, there are three means of persuading others: logos (logic), pathos (emotion) and ethos, (personal credibility). Aristotle told us that ethos is the most important, which makes sense because as listeners we can’t help but be swayed by our perception—mostly rapid and unconscious—of the speaker’s trustworthiness. We decide to trust or not trust rapidly and unconsciously and only afterwards justify our reasons for doing so.

One of the most important signals we pay attention to is the speaker’s title or position, because we are also hard-wired to pay attention to relative status and defer to those of higher status. When the speaker does not have the automatic credibility that comes from their title, they know they have to work hard to gain credibility and trust, so they take pains to gather data to back up their claims, think carefully about the logic, and present it in terms of what the listener will most care about. In short, they prepare. But preparation takes time and effort, and if you’re a leader with a lot more important issues on your plate, it makes sense, doesn’t it, to save either one if you can?

Be honest: if people took everything you said at face value, would you take the time and effort to gather evidence to support what you know to be true? If people are prepared to do what you say without question, how much time would you devote to explaining your reasons, or crafting your message for maximum impact?

When a tool works for you every time, you use it more and stop using others. When “because I said so” gets the compliance you want, why rely on logos? Why make the effort to carefully prepare your case, to anticipate objections, to polish your prose, to weigh your words before you speak?

How to avoid the ethos trap

It takes a lot of self-awareness, discipline and humility to avoid falling into the ethos trap, but a little reminder can go a long way. You can’t hire a slave to whisper in your ear, “Remember you are mortal”, as Roman generals did when they were honored by a triumph after a major victory, so you need to remind yourself.

Fortunately, there’s a reasonably simple fix, as long as you remember to think about it. Researchers have shown how easy it is to induce feelings of greater or lesser power in their test subjects, and what works for them can work for you too. Any time you’re preparing for an important meeting with subordinates, you can prime your mind with a little humility in some easy ways. You can think of a time when you felt powerless; think of someone more powerful than yourself, and you can imagine that you have to convince them; prepare as if you’re presenting to your boss, and everybody has a boss, even if it’s the Board or Wall Street analysts.

In my next article of this series, I will explain why, even as your skills tend to get rusty, you fall into the second trap of leadership communication and you care less about what others think.