This past Memorial Day focused our attention on the sacrifices of the soldiers, sailors and airmen who won World War II. As the son of one of those warriors who fought in the air over Europe, I am as admiring and respectful of their achievements as anyone else. However, his B-17 bomber did not make itself, nor did the millions of tons of equipment, clothing and food that sustained them in their fight.

Those all came from the astounding ability of the American economy to convert itself to war production, as recounted in a fascinating new book, Freedom’s Forge, by Arthur Herman. That book is well worth reading for several reasons, but here I concentrate on one of the true heroes of the American war effort, Henry J. Kaiser. The two main purposes of business are to make things and to sell things, and Kaiser was a genius of both.

Kaiser’s sales skills were honed early in his life. A restless child, he quit school at 13 and was a traveling salesman at 16. His first business failed, and when he met his future wife at the age of 23, her well-off father agreed to the marriage only on the condition that he could save $1,000 and earn at least $125 a month. Kaiser took a train to Spokane Washington and began making the rounds of local businesses in search of a job. When that failed, he opted for a targeted approach and began pestering McGowan Bros. Hardware for a job. He showed up one day after a fire had swept through the business, and McGowan said, “Are you crazy? Can’t you see I’m ruined?” Kaiser offered to salvage what inventory he could and sell it. With the store back in business, within 10 months he was earning $250 a month and had bought a house for his bride.

He soon got into the roadbuilding business. One of his employees was on vacation when he overheard two men discussing a contract that was going to be awarded for a major road to Redding, California. He called Kaiser, and soon the two were on the train to the town. Unfortunately, during the trip they found out that the train they were on was an express which did not stop in Redding. Unfazed, Kaiser decided to jump from the train when it slowed down three miles outside of town. They showed up bloody and dirty but won a half million dollar contract. It probably did not hurt that when they were in the waiting room, the receptionist mentioned that her feet were cold. Kaiser went out and bought her an electric heater and never had trouble getting an appointment.

In later years Kaiser’s business grew and in partnership with five other companies built the Hoover Dam and other massive projects. By 1940, as America slowly and belatedly woke up from its isolationist dream that it could stay out of the war, Kaiser was already a famous and accomplished businessman.

1940 was a grim year for Western civilization. By the end of that year, only Great Britain held out in Europe, but they depended on a fragile lifeline of cargo ships which were being sunk three times as fast as they could be built. Existing shipyard capacity in the US was taken up by the Navy, in a belated effort to gear up for a war that the American public still believed they could avoid.

Kaiser saw an opportunity and decided to compete for a contract to build cargo ships, in spite of two minor (for him) disadvantages. The most obvious was that he had no shipyard and would be hard-pressed to tell you what the pointy end of a ship was called.

The second, ironically enough, was his reputation for superb salesmanship. Jesse Jones, one of the top gatekeepers in determining who would get the business, actually forbade his people from meeting with Kaiser alone, complaining that they would come back from meetings saying, “Mr. Kaiser is wonderful; he convinced me to give him my watch.” One secret of his sales technique was that he had excellent questioning skills. It was said that he would ask questions to get the response he wanted, and then say “That’s a great idea”.

Yet Kaiser was persistent, and had a mesmerizing ability to sell a vision and engender confidence in his ability to deliver. His motto seemed to be: “Overpromise and overdeliver.” He concentrated on the British, and brought their buyers to an empty patch of mud flats in California. The confused buyers asked, “Where are your shipyards?” Kaiser said, “Right here. Give me the contract and within months there will be a shipyard here and thousands of workers.”

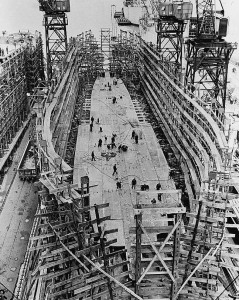

When he won the contract in December 1940, Kaiser called one of his men, Clay Bedford, and said “You’re going to build me a shipyard.” Bedford simply replied, “Where?” They had to build not only the facilities for shipbuilding, but also housing for the thousands of workers who began streaming in from all parts of the country. Starting from the mud up, the yard laid the first keel just four months later. Although they had never heard of the term “thinking outside of the box”, Kaiser, his son Edgar, and Bedford, used their unfamiliarity with shipbuilding to their advantage and revolutionized the construction process.

Kaiser knew how to spot top talent and get the utmost effort from each. Bedford and Edgar ran competing shipyards and strove to outdo each other. At the start, it took 220 days to build a Liberty ship. Both shipyards soon managed to whittle that down to less than 80 days, but still the Germans were sinking them faster than they could be built. The military clamored for faster production. By November 1942, Bedford made a special effort and built and launched the Robert S. Peary in 4 days and 15 hours, and it sailed the seas until 1963. Although that was more of a stunt than anything, it was said that they were launching ships so fast that one lady arrived at the shipyard to christen a new ship, but it was launched before she got there. She was told, “Don’t worry, Ma’am—just wait here and another will be along in a few minutes.”

In just 56 short months, Kaiser’s shipyards produced 1,490 ships.

Kaiser also had an uncanny ability to perceive a need well in advance of most people. In 1940, while most Americans were deluding themselves that they could avoid war, he realized that magnesium was going to be a metal of strategic importance, so he built four plants when everyone said he was crazy, and magnesium was delivered when it was needed in huge quantities.

Henry J. Kaiser proved on a colossal scale that the ability to anticipate a need, overcome obstacles and sell the vision, and then to deliver on the promise—are qualities that not only win sales but can help win wars.