When Is It Your Duty to Disagree?

When the group consensus says one thing and you think another, should you speak up? When do you have a duty to disagree?

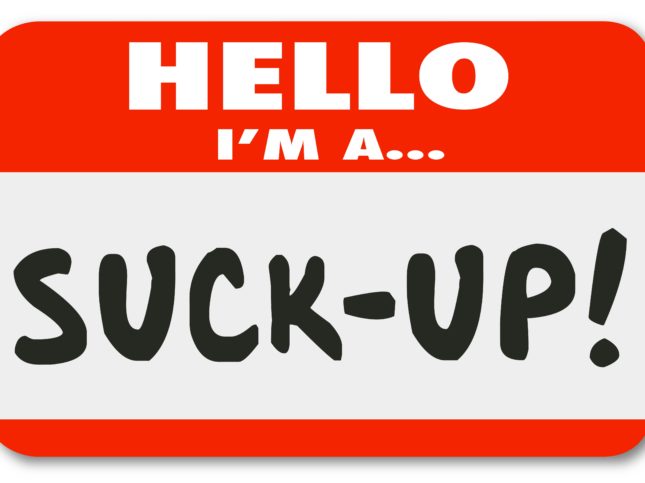

Common sense tells us there are a lot of good reasons to keep quiet. We all know you “need to go along to get along”, and “the nail that sticks out gets pounded down”.

In his new book, Conformity: The Power of Social Influences, Cass Sunstein says there are two main reasons we don’t speak up even when we disagree with the group. One reason is that we may be wrong. If the question is complicated or we lack complete information, we may not be totally sure of our own position, so we look to what others are saying or doing for information. Second, we crave acceptance by our group, and disagreement threatens that acceptance.

These two reasons can exert enormous power even when the answer is fairly clear-cut. Solomon Asch conducted some famous experiments in which subjects were shown a line, and then asked to select which one of three lines matched the length. It was a simple task, and by themselves, they were right almost 100% of the time. But when others in the room (who were secretly planted by the researchers) chose a different—and wrong—line, they got it wrong 37% of the time. Even though it was obviously wrong, more than a third of the time, they let the group consensus win. And the majority were willing to keep their mouths shut: in twelve iterations, 70% of subjects got it wrong at least once.

That still leaves a third of people who were willing to speak up and disagree with the group, but remember that the question was pretty clear cut. I don’t have statistics, but it’s a safe bet that when the question is more nuanced, rugged individualists are few and far between.

Lack of disagreement makes a group run more smoothly, but there may be a price to pay. When getting along becomes more important than results, performance can suffer. Investment clubs that are formed on the basis of social connections perform worse than those formed by people who weren’t socially connected, for the simple reason that members were much more likely to openly disagree. Unanimous decisions were worse than split decisions.

It reminds me of the story of GM CEO Alfred Sloan who once ended a meeting by saying:

“If we are all in agreement on the decision – then I propose we postpone further discussion of this matter until our next meeting to give ourselves time to develop disagreement and perhaps gain some understanding of what the decision is all about.”

The “go along at any price” crowd think that those who disagree are selfish, because they put their own views ahead of the group’s. But the truth is, disagreement comes with a price, so if you’re willing to pay that price for the good of the group, disagreement is a totally unselfish act. In fact, you have a duty to speak up, regardless of what it may cost.

The good news is that your risk may pay off. Even when the group seems unanimously united in opposition, remember that up to two thirds of them may harbor doubts but are afraid to speak up. By saying out loud what they are privately thinking, you may encourage them to join you. (And if you are right, you also have two other powerful allies on your side: time and truth.)

But be smart about it: choose your battles. Your best guide to decide whether you have a duty to speak up is the first rule of lean communication: you must add value. When you are aware of an opportunity to improve the situation but don’t take advantage of it, not only are you not adding value, you may even be subtracting value.

Are we all in agreement?