How Can You Expect Them to Remember If You Can’t?

Memory is the forgotten asset of persuasive presentations.

Memory is the forgotten asset of persuasive presentations.

Throughout Western history, a strong memory was a crucial part of a speaker’s tools. Educated people have learned to influence others through the formal study of rhetoric, which is basically nothing else than the art of persuasive communication. Even though very few people formally study rhetoric anymore, its lessons are just as relevant today as they have been for the past two millennia. The study of rhetoric generally focused on five major areas: discovery of the right arguments, arrangement of your material, your style, memory, and delivery. Four of these are clearly relevant to speakers today, but memory seems to have been discarded as an asset. I believe this is a serious mistake.

No one memorizes anything anymore. Why should we, when we have so many terabytes of data instantly available to us when we need it? Why remember phone numbers when we can store them in our phones? Why learn anything when we can pluck it from the cloud? And—to kick everyone’s convenient scapegoat—why remember the material of our presentations when we can store it in our slide deck?

Why, indeed? Picture this scenario: The presenter has grabbed your attention; he or she has made a compelling case that you need to change your ways, has shown a clear path to a bright future for all, and is just about to clinch their argument through a masterful and passionate call to action. They look their listeners squarely in the eyes, and say: “For these three reasons, uh…(pause to look back at the slide showing behind them, then proceed to read the bullet points) first,…”

It’s hard to be convinced of anyone’s command of their subject matter if they are clearly relying on a crutch to help them remember it. Remember Rick Perry? I didn’t think so. He could be the Republican nominee today if he had not had his famous memory lapse, when he said he would eliminate three federal agencies if elected, but forgot the third.

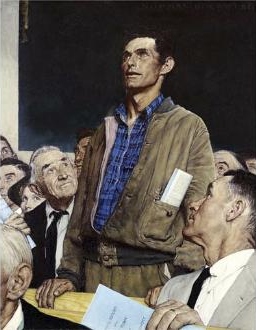

For a spectacularly positive example of what memory can do for a speaker, you only have to think of one of the greatest speeches in American history, King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. He didn’t call it that, because those words were not even in the original script. However, as he gauged the mood of the audience, he decided to use those lines, pulling them out of memory because he had used them in speeches before. Now, no one will ever forget those words.

When I advocate memory, I am definitely not talking about rote memorization of your material. That’s the surest way to appear mechanical and insincere, and if you blank out on just part of it, you may derail your entire presentation. What I am referring to, is knowing your material so deeply and intimately that you can speak about it off the cuff if necessary, without slides.

Want to be spontaneous? Know the material so well that you can focus on the audience’s reactions and be able to make adjustments as needed, secure in knowing exactly where you are and where you want to go next. When you obviously know your content so well that you can be interrupted by an off-topic question and return to where you were; when you can blank the screen and speak directly to your audience and focus your full attention on them; when you can reel off facts and details as needed, or hold them in reserve; imagine what it does for your credibility and your personal confidence.

What can you do to improve your memory?

The ancients learned mnemonic techniques that are still taught today by memory courses, but you don’t need rote memorization; you just need to know your message and material deeply enough that you can reconstruct the parts you need at the speed of real time conversation.

How do you know that your grasp of the material is strong enough? Even if you plan to use slides, you should always rehearse your presentation at least once without them. It will help you figure out where you need to embed some of the material more firmly, and it might even point out some spots where you can eliminate a slide or reduce some of the text on it, either because it’s unnecessary or because it disrupts the flow. By all means, practice like you’re going to deliver it, using your slides, but as a final exam, rehearse at least once without slides. In fact, testing yourself in this way is actually the best way to learn it.

Another technique is to put your main points on individual index cards. You can keep them in a pocket and only refer to them if you get stuck. All the times I’ve done this, I’ve never once had to pull them out, but it definitely helps personal confidence to know you have them.

Don’t be afraid to try it. Although it doesn’t relate directly to knowledge of your content, about ten years ago, I was very impressed when another trainer quickly memorize the names of everyone in the class of about fifteen people, and that was the last time I’ve ever used name cards in a session. It only seemed tough until I tried it.[1]

The nice thing about learning your subject matter thoroughly and in detail is that memory is cumulative and compounding. For similar types of presentations, you will already have a strong base to begin from, and learning new things is easier because you have so much more in your mind to connect it to.

I hate to close on a negative, but if you have trouble being able to deliver your presentation without memory aids, that suggests either that you don’t know the material that well, that it’s too long, or it’s just not that clear. It also implies to the audience that you didn’t care enough to prepare for them. As the song says, “every way you look at it you lose.”

[1] It’s very situational, though. If I learn your name in a class, don’t be disappointed if I see you the next day and have completely forgotten it.