The Three Minute Presentation that Helped Save the World

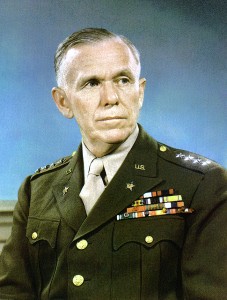

On May 13, 1940, as the Western front was reeling under Hitler’s blitzkrieg attack on France and the Low Countries, the United States had a small third-rate army, equipped with obsolete weapons. The new Army Chief of Staff, George Marshall, was trying to change that, but President Roosevelt wasn’t buying.

That morning, Marshall accompanied Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, according to the story as told by Thomas Ricks in The Generals: American Military Command from World War II to Today, to the White House to make the case for a major increase in spending to build up the military. Roosevelt made it clear that he did not want to talk to them, and after Morgenthau spoke in support of the measure, Roosevelt cut him off and said, “Well, you filed your protest.”

Morgenthau then asked the President to listen to Marshall, but FDR said, “I know exactly what he would say. There is no necessity for me to hear him at all.” Others in the room sat quietly, offering no support. As the meeting ended, Marshall approached Roosevelt’s desk and said, “Mr. President, may I have three minutes?”

The President assented, and then began to say something else, but Marshall, afraid that he might not get to speak, spoke right over him. He spoke rapidly, full of facts and figures, saying, “If you don’t do something…and do it right away, I don’t know what’s going to happen to this country. You have got to do something, and you’ve got to do it today.”

At this point, he had FDR’s full attention, and he went on: “We are in a situation now where it’s desperate. I am using the word very accurately, where it’s desperate.”

It must have been a powerful presentation, because the next day, Roosevelt asked Marshall for a list of what the military needed.

What can we learn from this extremely short but momentous speech? That sometimes it is possible to dramatically alter the listener’s attitude and position quickly if that’s the only chance you have. You too, can pull off this feat, as long as you have:

Command of the facts: It begins with content: your proposal has to be grounded in reality, and you must have the facts to back up your position. You must command your material so well that without overwhelming the listener with detail, you leave no doubt that you have all the details if needed. Besides being convincing, facts also provide a face-saving way for the listener to change his mind. When it’s about opinions, it’s hard to change someone’s mind because it can get personal.

Conviction: Conviction is not the same as passion, which is easily dismissed by the listener as purely emotional. Conviction comes from a solid foundation of thought, and the deep belief that your cause matters. It certainly contains a strong core of emotion, but that emotion may actually be more powerfully expressed by keeping it in check.

Courage: It takes tremendous guts to stand up to the President of the United States, but Marshall had the character and devotion to duty that in effect left him with little choice. But the collateral benefit of having the courage to state the truth to power, even when it can be personally very costly, is that it can confer tremendous credibility.

One final thought: Marshall already had a reputation in the Army for his ability to boil down complex issues to succinct statements. It was a skill he had honed over years, and it paid off for his country when it was needed most.