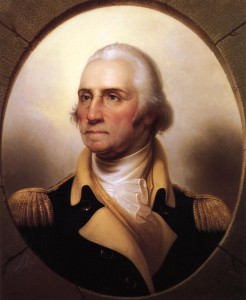

How George Washington Saved the Nation With a Speech–and a Prop

One of the most dramatic and important moments in American history was marked by what did not happen rather than by what did happen, and it’s all because of the masterful persuasive power of George Washington.

One of the most dramatic and important moments in American history was marked by what did not happen rather than by what did happen, and it’s all because of the masterful persuasive power of George Washington.

On March 15, 1783, General Washington attended a meeting of mutinous officers who were angry about not being paid by the Continental Congress and who were agitating for a march on Philadelphia to take over the government. If this happened, the ideals for which they had fought in order to earn their independence from Great Britain would probably have died. The revolution would have thrown away its high-minded legitimacy and the United States as we know it would probably never have come into existence.

Washington was there to prevent this from happening, and how he did it is one of the most dramatic stories of persuasion that most people have not heard of. We’ll see what happened, but first it’s important to set the stage by describing some of the persuasion lessons that Washington had already learned and taught by his example in the preceding years, that allowed this moment to play out the way it did.

When Americans think of George Washington today, most of us see the marble demi-god, and not the real man behind the myth. It’s easy to think that he accomplished everything he did through his position and authority as the commander in chief who could summon up his armies to back up his will. In fact, Washington had very little real power to get things done. Partly this was because he did not want it: he was acutely conscious of the need for civilian control, even when this meant that things would not get done, taxes would not be collected, and his army would not be fed. Washington bent over backwards to influence rather than to coerce.

He jealously guarded his image—wanting to be seen as strong and above it all. He never let a sign of weakness or pettiness leak out of the confines of his tent. Much of this was out of personal vanity, but it was also strategic: he saw the need to stand as an irreproachable symbol of the United States. He knew that it was critical to win the public relations battle in Europe and get France involved in the war on the side of the Americans, and his image was a valuable asset in that campaign.

Because his image was so pure, ethos[i] was his strongest persuasive asset. He had earned it through leading from the front in spite of severe personal danger often being at the front in battle after battle; he refused a salary during the war, even though his treasured Mount Vernon was being mismanaged and run into debt. He gradually became less aristocratic in his attitudes and grew to love the common men in his army through familiarity and shared sacrifice.

So, by the time Washington appeared in front of his officers, he had earned their trust, respect and veneration. But they had heard many empty promises and so were suspicious even of him.

And his speech was well-crafted and masterfully delivered. Although in most instances in speaking to a hostile audience, it’s best to start with some area of common ground and build from there, Washington began by scolding the anonymous authors for their actions, then softened his tone and reminded the officers that he had been with them from the beginning, suffering the same sacrifices and exulting in their common triumphs. He next appealed to their patriotism and then closed with a vision of the glorious example they could set for all mankind.

Yet in spite of this his speech did not go well. As he concluded, he noticed they still seemed uncertain, not sure how to react. Quite possibly, the fate of the young republic was balanced on a knife edge.

Washington’s heroic stature had brought him this far, but it was a small gesture of vulnerability that tipped the balance. From his pocket, he pulled a letter from Congressman Joseph Jones of Virginia, to show the officers that Congress meant to act on their concerns. He looked at the letter but did not speak. The men wondered what was wrong. Then, he took a pair of reading glasses from his pocket, which he had never worn in public. Putting them on, he said, “Gentlemen, you must pardon me. I have grown gray in your service and now find myself growing blind.”

These words electrified his audience. Witnesses said many were in tears as they listened. Finishing the letter, Washington did not say another word, but turned and left the hall. The officers unanimously approved a resolution affirming their appreciation for their commander in chief and pledging their loyalty to Congress, and the nascent republic was saved.

Ironically, Washington’s spent his life as a model of strength and fortitude, yet his one public moment of weakness led to his greatest oratorical triumph.

If you’re tempted to try this, keep in mind that vulnerability will backfire if you’re not already perceived in a strong light—that is, when your ethos is already strong.

[i] Ethos, as you will recall, is Aristotle’s name for the personal qualities of the speaker that make him or her persuasive.

More interesting stuff, Jack!

I think that, amongst other things, this story speaks to the power of genuine vulnerability. Unfortunately, this often gets mistaken for “weakness,” which I think is incredibly inaccurate du to the fact that it often takes great strength and courage to express oneself in a truly vulnerable way to others.

Once again, another thought-provoking article – thanks for your continued commitment to a great blog, Jack!