How To Present Technical Information Effectively

They say an expert is someone who learns more and more about less and less until finally he knows everything about nothing. I’m not sure if that’s true, but many of the senior executives I speak with come away from encounters with experts feeling they’ve been told a lot but still understand nothing.

They say an expert is someone who learns more and more about less and less until finally he knows everything about nothing. I’m not sure if that’s true, but many of the senior executives I speak with come away from encounters with experts feeling they’ve been told a lot but still understand nothing.

One of the most common issues that I am asked to address in my coaching sessions is how to communicate complex and difficult information to a lay audience. My coaching clients, who include engineers, scientists, and lawyers, sometimes understand on their own that they take too long to express their ideas, and are frustrated by it. More often, they’ve been counseled by others that they must be more concise and clear. As one senior person in a high-tech company told me when he hired me to coach his staff: “I ask people what time it is, and they tell me how to build a watch.”

The real issue is not in making your listeners understand—it’s how to help them get it efficiently. When you furnish excessive detail to explain difficult information, you bump against the limits of attention and of working memory. Details that appear simple to you require time and effort for others to absorb. Too much detail is like pouring water into a funnel too quickly. While they’re still making sense of what you just said, they’re not grasping what you’re saying now. Then they get frustrated and give up.

Why does this happen?

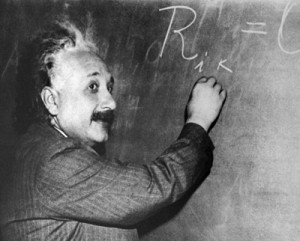

You want to show how smart you are. I actually had a scientist in one of my classes demonstrate great honesty when he said: “If we just give them the answer, they won’t value it, because they don’t know how hard it was to get to that answer.” That may be true in some ways, but as Einstein said, “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.” Conciseness confers credibility.

You think out loud. When someone takes you by surprise by asking about an angle you haven’t thought of before, it’s natural to respond immediately and formulate you answer as you talk. Don’t be afraid to pause momentarily to gather your thoughts; you don’t get extra points for quick responses.

You don’t know why the listener needs the information. When you’re not sure what they will do with the information, you want to cover all possible contingencies. Don’t be afraid to ask them what they need to know and why.

You present it the way you learned it. You are accustomed to gathering evidence and using it to reach conclusions. This is great for accumulating expertise, but the best way to pass it on is to deliver the conclusion first and then provide evidence as necessary. Learn it from the ground up; teach it from the top down.

Curse of knowledge. When you learn something, you quickly forget what it was like not to know it, so you tend to start at a level that is too complex for your listeners. Paradoxically, even though your listeners say you give too much detail, experts often leave out a lot of detail that is necessary for full understanding.

What can you do about it?

Know your audience. What do they know already? The only way to learn something new is to build off existing knowledge. If your audience is mixed, it’s better to err on the side of less detail and handle the additional questions from the more sophisticated members in the Q&A or off-line.

Ask SO WHAT? One of the reasons you are an expert is that you are fascinated by the details of your particular topic. Your listeners don’t care that much. Use only details that pass through the “so what” filter. How much do they already know? What do they need to know? Why do they need to know it? What will they do with the information?

Find the headline. Then add detail as requested or needed. Headlines add value because they tell the listener the gist of the story. They give the listener a central point to hang the upcoming information on and make sense of it. The discipline of finding the headline will clarify your own thinking and it will force you to know your audience because the headline might be different for different listeners. They’re going to forget most of what you told them anyway, so having a clear headline increases the chances that they will remember the part you want them to remember.

Take a stand. This is closely related to finding the headline. If you are asked, “Will this work?”, or “Is this legal?”, all your instinct and training tells you to straddle the fence. After all, sometimes the only right answer is “it depends.” The problem with giving the caveats right up front that it’s like starting a document with the fine print and the footnotes. First, no one will listen to the end, and second, they will resent the fact that you’re putting the burden on them. Your credibility hinges on your level of decisiveness.

Answer their question. If they ask you a simple question, you might think the question is too simplistic and they need more context to understand what the real issue is. However, often they have a higher and wider field of view than you do and have their own reasons for asking the question that you are not privy to; respect that.

Pay attention to your listeners. I hate to stereotype, but technical presenters are often much more interested in their material than in the audience. Read their reactions, check for understanding, and make adjustments as necessary.

If you want your expertise to be relevant, you must be heard. Simply, shorten, and address the needs of the listener, and you will be relevant.

TJ, that is an excellent point. I had never thought about it that way, and I hope you don’t mind if I use that in future training classes. I’ve always found that technical folks can be just as good as anyone else in presenting and communicating if they have an approach they can buy into. Your approach sounds like just the ticket.

Jack, well thought out analysis. You are absolutely correct that most technical presenters focus on their own stuff an dnot their audience. My approach is to get the speakers to think of the speech as an engineering problem that can only be solved if they have proof that the audience understands and remembers the key points.