What possible use does the ancient art of rhetoric have in the twenty-first century? Although rhetoric was once an indispensable part of any real education, it began to go out of style in the 19th century, and is rarely taught in colleges today. If fact, the term itself has become mostly derogatory, signifying ornate, empty and manipulative language.

Fortunately, there are still a few people such as Sam Leith keeping the flame burning. His book, You Talkin’ to Me?: Rhetoric from Aristotle to Obama shows us that rhetoric does not have to be ornate, formal language, nor is it only empty wordsmithing. In fact, as Leith says, the only time we use rhetoric as a pejorative is when the rhetoric is obvious. Any time a person uses language to influence another, they are using the time-tested tools of rhetoric, and so much of what has been written about presentations and persuasive communication (including my own material), is a restatement or an elaboration of what Aristotle, Cicero, and Quintilian wrote so many centuries ago. The only reason we still recognize those names today is because they were so good at it, and because they knew how to pass on their knowledge to others so well.

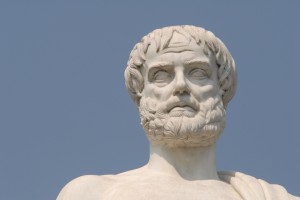

Aristotle was the first to give us a written definition, and you can’t get any more clear or comprehensive that it: finding the available means of persuasion.

Rhetoric covers five major subjects, and they are still useful today, whether you are selling a product, trying to get an idea approved internally, or running for President.

Invention: Finding the right arguments. What is the approach that is likely to work for this audience, for this particular decision at this time? As you can see, it’s not just about what you see as the best reasons, but about what will resonate with the other person. The right approaches usually require some combination of ethos, logos and pathos. In more modern terms, we might use Daniel Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2 thinking, but we have to appeal to both. When candidates try to encapsulate their campaign into a slogan, that’s invention.

Arrangement: There are various ways to arrange your material for best effect. Aristotle preferred the simple approach of just two main parts: in the narrative, you lay out the issue at question; then in the proof you give the reasons why your idea is superior. Other manuals recommended up to six parts, but the main thing is that a clear structure helps you think clearly and makes it easy for the audience to follow.

Style: How do you say it? Style seems to command most of the attention today. Most of the negative perception around rhetoric applies to the grand style, with big words and flowery sentences. Most of us prefer speakers who are authentic and use clear and plain language. But Barack Obama showed that we can still respond to the high style on the right occasion. The most effective speakers match their style to the audience and the occasion.

Memory: in ancient times, speakers were expected to speak at length without notes, and had to learn mnemonic techniques to make sure they could remember it all. Of the five subjects, memory may seem to be the least relevant today, but the way that speakers so often use slides as a crutch suggests that they may benefit from it.

Delivery: In today’s attention-deficit world, delivery is extremely important, because it’s the only way to maintain an audience’s attention long enough to persuade them. We no longer have to worry about projecting our voices to be heard by hundreds, but we still have to appear confident, open, and in control.

I suppose you don’t have to study formal rhetoric to be an excellent speaker and persuader, but why not learn from the best?